While disasters are common throughout the history of mankind, one of the worst environmental disasters began in China in 1958. It all started when Mao Zedong, the leader of the People’s Republic of China, was looking for ways to improve life in China.

Mao Zedong undertook several massive campaigns aimed at modernizing and improving life. One of these campaigns was the “Four Pests Campaign,” part of the “Great Leap Forward” between 1958 and 1962.

Mao Zedong’s Four Pests Campaign

During the 1950s, the People’s Republic of China was still struggling from decades of war and bouts of famine and sickness. In order to kick-start major change, Chinese leader Mao Zedong implemented the “Great Leap Forward” plan in 1958, and with it came the “Four Pests Campaign.”

The campaign was introduced as a hygiene campaign in an attempt to eradicate the pests that were responsible for the transmission of pestilence and disease. Mao Zedong reached the conclusion that several pests needed to be exterminated — mosquitoes, flies, rats, and sparrows, specifically the Eurasian tree sparrow — that ate grain, seeds, and fruit. According to environmental activist Dai Qing:

“Mao knew nothing about animals. He didn’t want to discuss his plan or listen to experts. He just decided that the ‘four pests’ should be killed.”

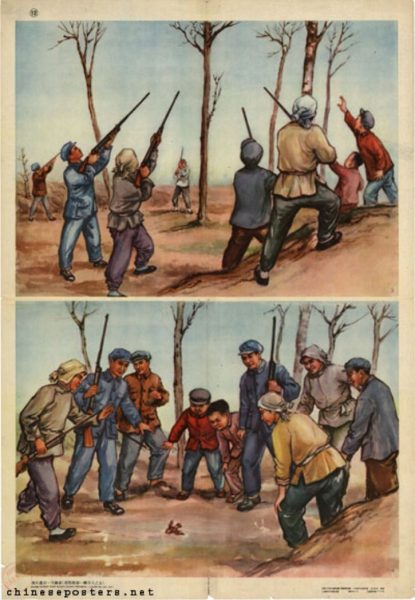

So the extermination known as the “Great Sparrow Campaign” and “Kill a Sparrow Campaign” began because they ate too much grain. The people were mobilized against this new common enemy; citizens would bang pots and pans so the sparrows would not have the chance to rest and would fall dead from the sky from exhaustion.

Mao reached the conclusion that several pests needed to be exterminated — mosquitoes, flies, rats, and sparrows, specifically the Eurasian tree sparrow — that ate grain, seed, and fruit. (Image: via chineseposters.net

Sparrow nests were destroyed, eggs were broken, and chicks were killed. Some citizens resorted to simply shooting the birds, while enterprises, government agencies, and schools held contests on who could kill the most. According to Time, Peking People’s Daily wrote:

“At dawn one day last week, the slaughter of the sparrows in Peking began, continuing a campaign that has been going on in the countryside for months. The objection to the sparrows is that, like the rest of China’s inhabitants, they are hungry.

“They are accused of pecking away at supplies in warehouses and in paddy fields at an officially estimated rate of four pounds of grain per sparrow per year. And so divisions of soldiers deployed through Peking streets, their footfalls muffled by rubber-soled sneakers.

“Students and civil servants in high-collared tunics, and schoolchildren carrying pots and pans, ladles, and spoons, quietly took up their stations. The total force, according to Radio Peking, numbered 3,000,000.”

Some sparrows found refuge in various diplomatic missions; the Polish embassy in Beijing denied Chinese requests to enter the premises to scare away the sparrows. This resulted in the embassy being surrounded by people with drums.

After two days of constant drumming, the sparrows were dead. These mass attacks depleted the sparrow population, pushing it to near extinction.

Insects, and lots of them

While many infectious diseases were eradicated, 1 billion sparrows, 1.5 billion rats, 100 million kilograms of flies, and 11 million kilograms of mosquitoes were outright decimated. However, by April 1960, it became evident sparrows didn’t only eat grain seeds, they also ate a large number of insects.

In the year following the campaign, there was a soaring insect infestation of crop fields. With no birds to control them, insect populations expanded in huge numbers. Locusts, in particular, swarmed over the country, eating everything they could.

While many infectious diseases were eradicated, 1 billion sparrows, 1.5 billion rats, 100 million kilograms of flies, and 11 million kilograms of mosquitoes were outright decimated. (Image: via chineseposters.net)

The crops were getting decimated in a way far worse than if birds had been allowed to live. Consequently, rice production, in particular, was hit the hardest, although grain production in most rural areas had also collapsed, creating one of the worst environmental disasters.

Rather than increasing, rice yields and grain production after the campaign substantially decreased. On the advice of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, Mao Zedong declared a stop to the “Great Sparrow Campaign,” replacing the birds with bed bugs on the Four Pests list. However, it was too late; the impact of this ill-conceived decision had already started a domino effect toward destruction.

The “Great Leap Forward,” the program that was meant to elevate China’s status, was now headed toward its downfall instead.

The repercussions

Already burdened by a lack of food even before the “Great Leap Forward” campaign, the overflow of insects, plus the added effects of widespread deforestation and misuse of poisons and pesticides, were a significant contributor to the Great Chinese Famine (1958-1962) in which millions of people died of starvation.

People simply ran out of things to eat; the official number of fatalities by the Chinese government was 15 million. However, it’s estimated by some scholars fatalities were as high as 45 or even 78 million. Chinese journalist Yang Jisheng, who chronicled the famine in his book Tombstone, estimates the deaths at 36 million people. (The book, published in the U.S. last year, is banned in China.)

Over 50 years later, the Great Famine remains a taboo topic. This is because of the extreme measures people had to go to in order to stay alive. Yang told NPR that unbearable hunger made people behave in inhuman ways. Even government records reported cases where people ate human flesh from dead bodies.

“Documents report several thousand cases where people ate other people.

“Parents ate their own kids. Kids ate their own parents. And we couldn’t have imagined there was still grain in the warehouses. At the worst time, the government was still exporting grain.”

That’s right, some deaths were unnecessary during one of the worst environmental disasters. While the fields were empty, massive grain warehouses held enough food to feed the entire country: however, the government never released it. They also ruthlessly, sadistically, and brutally detained, beat, and hunted down anyone who appeared to question the situation.

Playing it all down

China has continuously played down the causes and effects of the Great Famine, which is officially known as the “Three Years of Difficult Period” or “Three Years of Natural Disasters.” The truth is slowly coming out; however, the full truth may never come out in mainland China, at least not officially. Yang told The Guardian:

“Because the party has been improving and society has improved and everything is better, it’s hard for people to believe the brutality of that time.

“Our history is all fabricated. It’s been covered up. If a country can’t face its own history, then it has no future.”

Follow us on Twitter, Facebook, or Pinterest