Astronomers are back in the dark about what dark matter might be, after new observations showed the mysterious substance may not be interacting with forces other than gravity after all. Dr. Andrew Robertson of Durham University presented the new results to the European Week of Astronomy and Space Science in Liverpool.

Three years ago, a Durham-led international team of researchers thought they had made a breakthrough in ultimately identifying what it is.

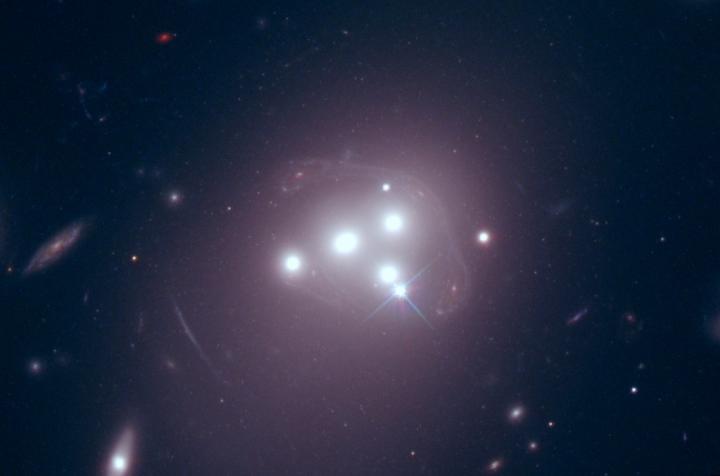

Observations using the Hubble Space Telescope appeared to show that a galaxy in the Abell 3827 cluster — approximately 1.3 billion light-years from Earth — had become separated from the dark matter surrounding it.

Such an offset is predicted during collisions if it interacts with forces other than gravity, potentially providing clues about what the substance might be.

The chance orientation at which the Abell 3827 cluster is seen from Earth makes it possible to conduct highly sensitive measurements of its dark matter.

However, the same group of astronomers now says that new data from more recent observations shows that dark matter in the Abell 3827 cluster has not separated from its galaxy after all. The measurement is consistent with it feeling only the force of gravity.

A view of the four central galaxies at the heart of cluster Abell 3827, at a broader range of wavelengths, including Hubble Space Telescope imaging in the ultraviolet (shown as blue), and Atacama Large Millimetre Array imaging at very long (sub-mm) wavelengths (shown as red contour lines). At these wavelengths, the foreground cluster becomes nearly transparent, enabling the background galaxy to be more clearly seen. It is now easier to identify how that background galaxy has been distorted. (Image: Richard Massey (Durham University) via NASA / ESA)

Lead author Dr. Richard Massey, in the Centre for Extragalactic Astronomy at Durham University, said:

“The search for dark matter is frustrating, but that’s science. When data improves, the conclusions can change.

“Meanwhile, the hunt goes on for dark matter to reveal its nature.

“So long as dark matter doesn’t interact with the Universe around it, we are having a hard time working out what it is.”

Dark matter and dark energy

The Universe is composed of approximately 27 percent dark matter, with the remainder largely consisting of the equally mysterious dark energy. Normal matter, such as planets and stars, contributes a relatively small 5 percent of the Universe.

There is believed to be about five times more dark matter than all the other particles understood by science, but nobody knows what it is.

However, dark matter is an essential factor in how the Universe looks today, as without the constraining effect of its extra gravity, galaxies like our Milky Way would fling themselves apart as they spin.

The video below is a supercomputer simulation of a collision between two galaxy clusters, similar to the real object known as the “Bullet Cluster,” and showing the same effects tested for in Abell 3827. All galaxy clusters contain stars (orange), hydrogen gas (shown as red), and invisible dark matter (shown as blue).

Individual stars and individual galaxies are so far apart from each other that they whizz straight past each other. The diffuse gas slows down and becomes separated from the galaxies, due to the forces between ordinary particles that act as friction.

If dark matter feels only the force of gravity, it should stay in the same place as the stars, but if it feels other forces, its trajectory through this giant particle collider would be changed.

In this latest study, the researchers used the Atacama Large Millimetre Array (ALMA) in Chile, South America, to view the Abell 3827 cluster.

ALMA picked up on the distorted infra-red light from an unrelated background galaxy, revealing the location of the otherwise invisible dark matter that remained unidentified in their previous study.

Research co-author Professor Liliya Williams, of the University of Minnesota, said:

“We got a higher resolution view of the distant galaxy using ALMA than from even the Hubble Space Telescope.

“The true position of the dark matter became clearer than in our previous observations.”

While the new results show dark matter staying with its galaxy, the researchers said this did not necessarily mean that it does not interact. It might just interact very little, or this particular galaxy might be moving directly toward us, so we would not expect to see it displaced sideways, the team added.

Several new theories of non-standard dark matter have been invented over the past two years and many have been simulated at Durham University using high-powered supercomputers.

Robertson, who is a co-author of the work, and based at Durham University’s Institute for Computational Cosmology, added:

“Different properties of dark matter do leave tell-tale signs.

“We will keep looking for nature to have done the experiment we need, and for us to see it from the right angle.

“One especially interesting test is that dark matter interactions make clumps of dark matter more spherical. That’s the next thing we’re going to look for.”

The video below is a supercomputer simulation of a collision between two galaxy clusters, if dark matter didn’t exist. The resulting distribution of stars and gas disagrees with what is observed in the real Universe, which provides compelling evidence that dark matter is present in the real Universe.

To measure the dark matter in hundreds of galaxy clusters and continue this investigation, Durham University has just finished helping to build the new SuperBIT telescope, which gets a clear view by rising above the Earth’s atmosphere under a giant helium balloon.

Provided by: University of Chicago Medicine [Note: Materials may be edited for content and length.]

Follow us on Twitter, Facebook, or Pinterest