The atmospheric concentration of methane, a potent greenhouse gas, has almost tripled since the beginning of industrialization. Methane emissions from natural sources are poorly understood. This is especially the case for emissions from the Arctic Ocean. The Arctic Ocean is a harsh working environment.

That is why many scientific expeditions are conducted in the summer and early autumn months when the weather and the waters are more predictable. Most extrapolations regarding the amount of methane discharge from the ocean floor are thus based on observations made in the warmer months.

Oceanographer Benedicte Ferré, a researcher at CAGE Centre for Arctic Gas Hydrate, Environment, and Climate at UiT, The Arctic University of Norway, said:

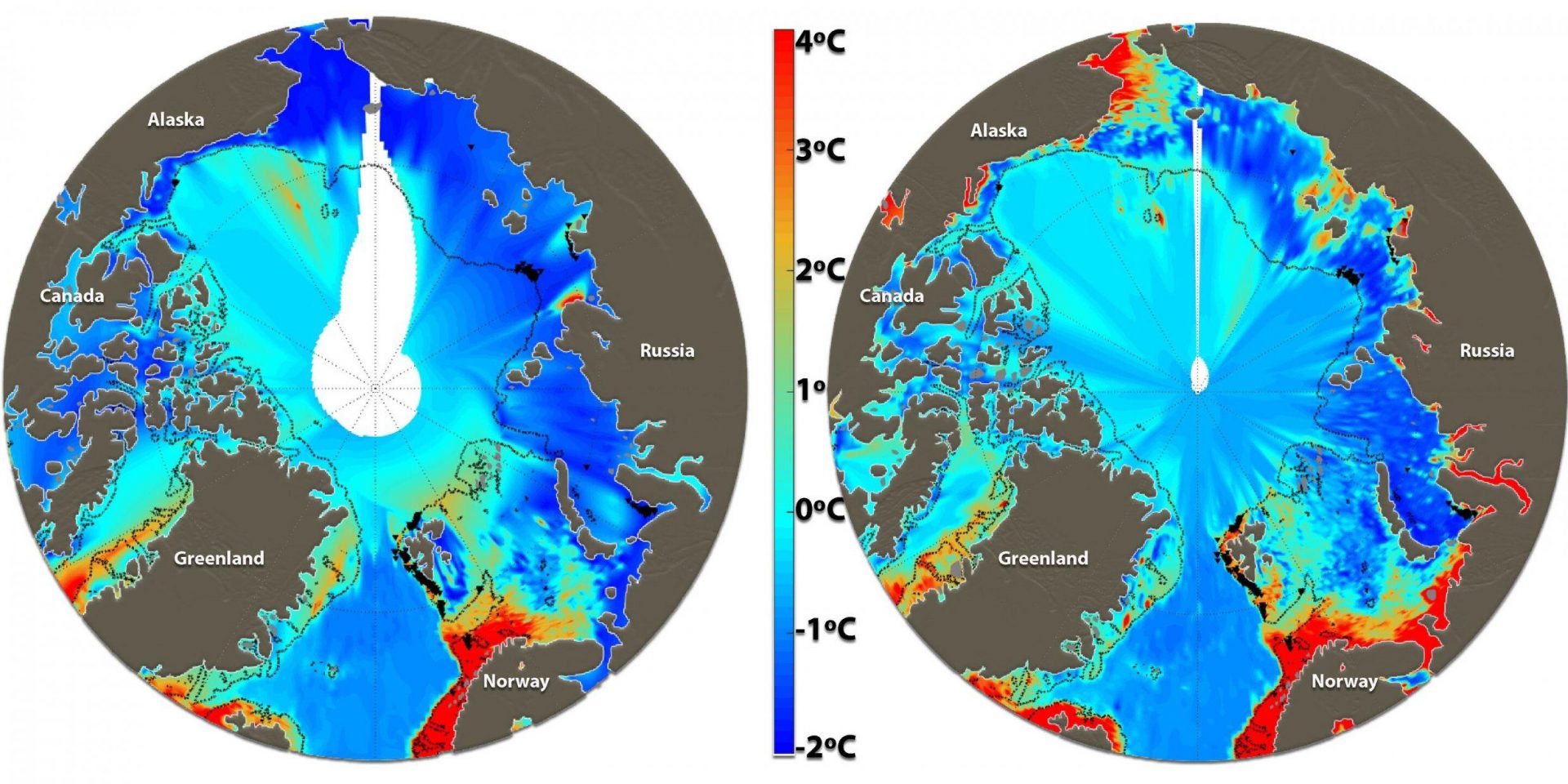

“This means that the present climate gas calculations are disregarding the possible seasonal temperature variations. We have found that seasonal differences in bottom water temperatures in the Arctic Ocean vary from 1.7°C in May to 3.5°C in August.

“The methane seeps in colder conditions decrease emissions by 43 percent in May compared to August.

“Right now, there is a large overestimation in the methane budget. We cannot just multiply what we find in August by 12 and get a correct annual estimate. Our study clearly shows that the system hibernates during the cold season.”

A frozen lid on top of large methane accumulations

The study was conducted west of the Norwegian Arctic Archipelago Svalbard — an area affected by a branch of the North Atlantic Ocean current called the West Spitzbergen Current. The observations were made at 400 meters of water depth, where the ocean floor is known for its many methane seeps. Ferré said:

“We see bubbles from the methane seeps as flares during echo sounder surveys. There are plenty of them in this area. They probably originate from free gas migrating upwards from reservoirs, through sedimentary layers or tectonic faults.”

The area in question is at the limit of the so-called gas hydrate stability zone. Gas hydrates are solid, icy compounds of water and, often, methane. They remain solid beneath the ocean floor as long as the temperatures are cold and the pressure is high enough. The bottom water temperatures affect the extent of the boundary of this stability zone. Ferré added:

“The hydrates form from the upward moving methane gas, in the uppermost sediments. This can happen rapidly given sufficiently cold-water temperatures. So, we get this hydrate lid containing these large accumulations of the greenhouse gas and slowing down the rate of emissions during cold periods.

“This lid then depletes during summertime, with warmer temperatures. The bottom-water warming affects the equilibrium and we get seasonal variations of the methane emissions.”

Seasonal changes strongly affect methane-consuming bacteria

Luckily, more than 90 percent of the methane released from the ocean floor never reaches the atmosphere. Partly due to the physical properties of the ocean itself such as currents and water column stratification. Methane is also consumed by specific bacteria (methanotrophs) in the water column. These are greatly affected by the seasonal variations described here. To a surprising extent. Co-author of the study published in Nature Geoscience, Helge Niemann, professor in geomicrobiology at the Royal Netherlands Institute of Sea Research (NIOZ), said:

“The activity of the methanotrophic bacteria decreases a lot in the colder periods. Which is somewhat logical as there is less methane to consume.

“However, methane discharge decreases by 43 percent, and one would think that bacterial activity decreased accordingly. But the bacterial activity goes down by some orders of magnitude in spite of there still being methane in the water. There is very little methanotrophs in the system during winter.”

Seasonal changes have been important for understanding primary production in the ocean for a long time. But biogeochemical processes, such as methane oxidation by bacteria, have not been considered to be strongly influenced by seasonal changes.

“In this paper, we prove that assumption wrong,” states Niemann. The next step is to do more winter cruises to account for seasonal changes related to West Spitzbergen current all the way from the Norwegian Arctic to East Siberian shelf.

Potential tipping point

How methane will react in future ocean temperature scenarios is still unknown. The Arctic Ocean is expected to become between 3°C and a whopping 13°C warmer in the future, due to climate change.

The study in question does not look into the future, but focuses on correcting the existing estimates in the methane emissions budget. However, Ferré said:

“We need to calculate the peculiarities of the system well, because the oceans are warming. The system such as this is bound to be affected by the warming ocean waters in the future. A consistently warm bottom water temperature over a 12-month period will have an effect on this system.

“At 400 meters water depth we are already at the limit of the gas hydrate stability. If these waters warm merely by 1.3°C this hydrate lid will permanently lift, and the release will be constant.”

Provided by: Center for Arctic Gas Hydrate, Climate, and Environment [Note: Materials may be edited for content and length.]

Follow us on Twitter, Facebook, or Pinterest