After almost 20 years of patient monitoring, an international team of astronomers has witnessed the very fabric of space-time being dragged around a rapidly-rotating exotic star known as a white dwarf. The effect is a consequence of Einstein’s General Theory of Relativity and the result was published in the journal Science.

When massive stars are born, they often are created in pairs, and at the end of their lives, they leave behind super-dense cores in the form of a white dwarf, neutron star or black hole. Neutron stars emit regular clock-like pulses that enable astronomers to map their orbits to outstanding precision. Dr. Ramesh Bhat from the Curtin University node of ICRAR, who has been involved in this study since 2005, said:

“This is an exotic stellar pair in which a tiny, super dense neutron star the size of Perth orbits another compact Earth-sized white dwarf star five times a day; both have masses about the same as our own Sun. It took 20 years of patient monitoring and careful scrutiny of data to figure out what is going on.”

Swinburne University’s Professor Matthew Bailes and his team began to map the orbit in a series of intensive observing campaigns at CSIRO’s Parkes 64-meter radio telescope. Over the course of two decades, it became evident that the stars’ motion required Einstein’s General Theory of Relativity to explain their complex dance.

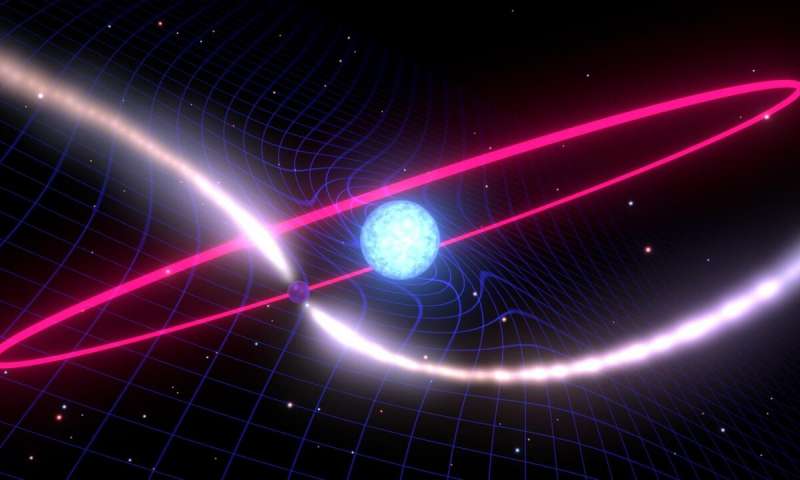

Artist’s depiction of a rapidly spinning neutron star and a white dwarf dragging the fabric of space-time around its orbit. (Image: Mark Myers, OzGrav ARC Centre of Excellence)

Lead author Max Planck Institute for Radio Astronomy’s (MPIfR) Vivek Venkatraman Krishnan (VVK) took up the challenge of untangling the many intertwined Einsteinian effects at play in this naturally-occurring gravitational laboratory during his Ph.D. at Swinburne University of Technology: VVK explained:

“At first the stellar pair appeared to exhibit many of the classic effects that Einstein’s theory predicted. We then noticed a gradual change in the orientation of the plane of the orbit.”

MPIfR’s Dr. Paulo Freire postulated that this might be, at least in part, due to the so-called “frame-dragging” that all matter is subject to in the presence of a rotating body as predicted by the Austrian mathematicians Lense and Thirring in 1918. Danish theorist Professor Thomas Tauris (Aarhus University) simulations helped quantify the magnitude of the white dwarf’s spin. Tauris said:

“In a stellar pair, the first star to collapse is often rapidly rotating due to subsequent mass transfer from its companion.

“In this system the entire orbit is being dragged around by the white dwarf’s spin, which is misaligned with the orbit”.

MPIfR’s Dr. Norbert Wex explained:

“One of the first confirmations of frame-dragging used four gyroscopes in a satellite in orbit around the Earth, but in our system the effects are 100 million times stronger.”

ICRAR’s Dr. Ramesh Bhat says that the effect makes the pulsar’s orbit tumble in space, adding:

“It provides yet another stunning confirmation of Einstein’s theory, which continues to shine in brilliance even after a century of its formulation. I find it truly fascinating.”

The result is especially pleasing for team members Bailes, Willem van Straten (Auckland University of Tech) and Ramesh Bhat (ICRAR-Curtin) who have been trekking out to the Parkes 64-meter telescope since the early 2000s, patiently mapping the orbit with the ultimate aim of studying Einstein’s Universe. “This makes all the late nights and early mornings worthwhile,” said Bhat.

Provided by: The International Centre for Radio Astronomy Research (ICRAR) [Note: Materials may be edited for content and length.]

Like this article? Subscribe to our weekly email for more!