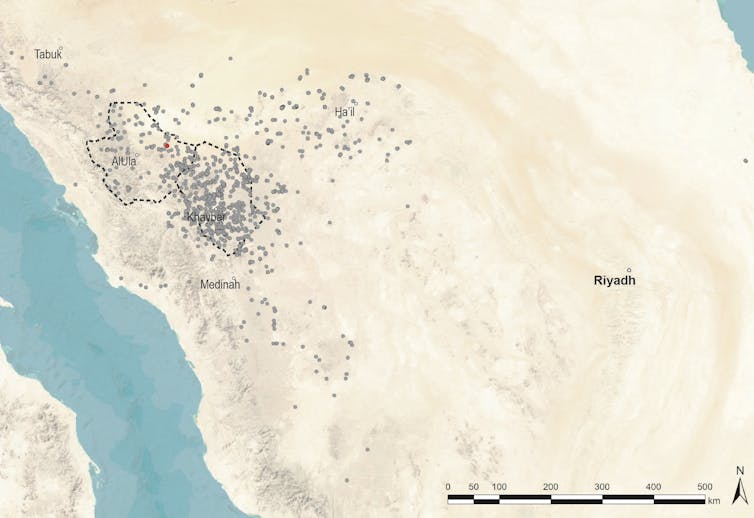

Over the past five years, archaeologists have identified more than 1,600 monumental stone structures known as mustatils dotted across a swathe of Saudi Arabia larger than Italy. The purpose of these ancient stone buildings, dating back more than 7,000 years, has been a puzzle for researchers. Our excavations and surveys reveal these were ritual structures, constructed by ancient herders and hunters who gathered to sacrifice animals to an unknown deity – perhaps in response to ancient climate change, the study was published in PLOS ONE.

Desert discoveries

In the 1970s, the first archaeological surveys of northwest Saudi Arabia identified an ancient and mysterious rectangular structure. The sandstone walls of the structure were 95m long, and although it was determined to be unique, no further study of this unusual site was undertaken. Over the following decades, airline passengers would see similar large “rectangles” dotted across the country. However, it was not until 2018 that one was excavated.

These structures are now known as mustatils (Arabic for rectangle). We have been studying them for the past five years as part of a larger archaeological study sponsored by the Saudi Royal Commission for AlUla.

The smallest mustatils are around 20m long, while the largest are over 600m. Previous work by our team determined that all mustatils follow a similar architectural plan. Two thick ends were connected by two to five long walls, creating up to four courtyards. Access to the mustatil was through a narrow entrance in the base. There would then have been a long walk, perhaps in the form of a procession, to the “head”, where the main ritual activity took place. Previous studies determined that the mustatils are at least 7,000 years old, dating to the end of the Neolithic period.

Cattle remains

In 2019–2020, we undertook excavations at a mustatil site called IDIHA-0008222. The structure, made from unworked sandstone, measures 140m in length and 20m in width. Excavations in the head of the mustatil revealed a semi-subterranean chamber. Within this chamber were three large, vertical stones. We have interpreted these as “betyls”, or sacred standing stones that represented unknown ancient deities.

Surrounding these stones were well-preserved cattle, goat, and gazelle horns. The horns are so well preserved that much of what we find is the horn sheath, made of keratin – the same substance as hair and nails. We found only the upper cranial elements of these animals: the teeth, skulls, and horns. This suggests a clear and specific choice of offerings. Further analysis suggests the bulk of these remains belonged to male animals and the cattle were aged between 2 and 12 years. Their slaughter would have formed a significant proportion of a community’s wealth, indicating these were high-value offerings.

Human remains

Current evidence suggests that the mustatils were in use between 5300 and 4900 BCE, a time when Arabia was green and humid. However, within a few generations, the ancient inhabitants of Saudi Arabia began to reuse these structures, this time to bury human body parts.

At IDIHA-0008222, a small structure had been built next to the mustatil. Inside were a partial foot, five vertebrae, and several long bones. Their placement suggests soft tissue was still present when they were buried. Forensic anthropologists were able to determine that the remains likely belonged to an individual aged between 30 and 40 years. Our work at other mustatils has revealed similar deposits of human remains. Were these remains buried in an attempt to claim ownership of the structure or some form of later ritual? These questions remain to be answered.

Pointing to water

The mustatils are changing how we view the Neolithic period not just in Arabia but across the Middle East. The sheer size of these structures and the amount of work involved in their construction suggests that multiple communities came together to create them, most probably as a form of group bonding. Moreover, their widespread distribution across Saudi Arabia suggests the existence of a shared religious belief, one held over a vast and unparalleled geographic distance. Currently, fewer than ten mustatils have been excavated, so our understanding of these structures is still in its infancy.

The key question to be answered is “why were they built?” A survey trip by our team may have, in part, solved this mystery. While recording these structures after rain, we noted that almost all mustatils pointed towards areas that held water. Perhaps the mustatils were constructed and the animals were offered to the god or gods to ensure the continuation of the rains and the fertility of the land. The possibility remains that the mustatils were built in response to a changing climate, as the region became increasingly arid like it is today.

Our study of the mustatils is ongoing. Our new project at the University of Sydney is focused on understanding why these monumental structures and others were built and what brought about their end. We hope future excavations and analyses will reveal further insights into the life and death of the mustatils and the people who built them.

Melissa Kennedy, Lecturer in Archaeology, University of Sydney, and Hugh Thomas, Lecturer in Archaeology, University of Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Follow us on Twitter, Facebook, or Pinterest