The vast majority of planets near foreign stars are discovered by astronomers with the help of sophisticated methods. An exoplanet like Beta Pictoris c does not appear in the image, but reveals itself indirectly in the spectrum.

A team of scientists from the Max Planck Institutes for Astronomy and Extraterrestrial Physics has now succeeded in obtaining the first direct confirmation of a previously discovered exoplanet using the method of radial velocity measurement. Using the GRAVITY instrument at the VLT telescopes in Chile, the astronomers observed the faint glint of the planet Beta Pictoris c, some 63 light-years away from Earth, next to the bright rays of its mother star.

The researchers can now determine both the brightness and the dynamic mass of an exoplanet from these observations and thus better narrow down the formation models of these objects. Combining the light of the four large VLT telescopes, astronomers in the GRAVITY collaboration have managed to directly observe the glint of light coming from an exoplanet close to its parent star. The planet called “Beta Pictoris c” is the second planet found to orbit its parent star.

It was originally detected by the so-called “radial velocity,” which measures the drag and pull on the parent star due to the planet’s orbit. Beta Pictoris c is so close to its parent star that even the best telescopes were not able to directly image the planet so far. Sylvestre Lacour, leader of the ExoGRAVITY observing programme said:

“This is the first direct confirmation of a planet detected by the radial velocity method.”

Radial velocity measurements have been used for many decades by astronomers, and have allowed for the detection of hundreds of exoplanets. But never before were the astronomers able to obtain a direct observation of one of those planets. This was only possible because the GRAVITY instrument, situated in a laboratory underneath the four telescopes it uses, is a very precise instrument.

It observes the light from the parent star with all four VLT telescopes at the same time and combines them into a virtual telescope with the detail required to reveal Beta Pictoris c. Marvels Frank Eisenhauer, the lead scientist of the GRAVITY project at MPE, said:

“It is amazing, what level of detail and sensitivity we can achieve with GRAVITY. We are just starting to explore stunning new worlds, from the supermassive black hole at the centre of our galaxy to planets outside the solar system.”

The direct detection with GRAVITY, however, was only possible due to new radial velocity data precisely establishing the orbital motion of b Pictoris c, presented in a second paper published also today. This enabled the team to precisely pinpoint and predict the expected position of the planet so that GRAVITY was able to find it. b Pictoris c is thus the first planet that has been detected and confirmed with both methods, radial velocity measurements and direct imaging.

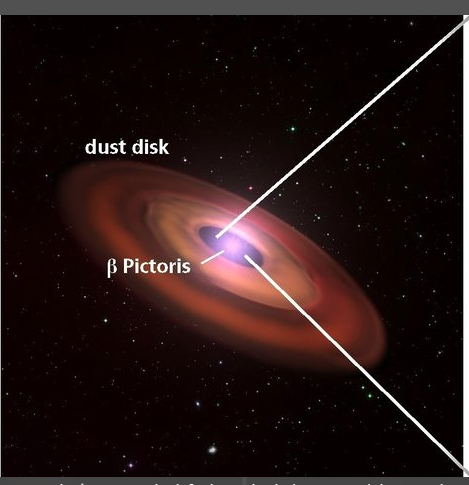

These schematic images show the geometry of the Beta Pictoris system: the image on the left shows both the star and the two planets embedded in the dusty disk in the orientation as visible from the vantage point of the Solar System. This view was constructed using the information from actual observations. The middle panel contains an artist’s impression of the disk/planet system. The image on the right shows the dimensions of the system when viewed from above and previous observations of Beta Pictoris b (orange diamonds and red circles) and the new direct observations of Beta Pictoris c (green circles). The exact orbit of planet c is still somewhat uncertain (fuzzy white area). (Image: Axel Quetz via MPIA Graphics Department)

In addition to the independent confirmation of the exoplanet, the astronomers can now combine the knowledge from these two previously separate techniques. Mathias Nowak, the lead author on the GRAVITY discovery paper explained:

“This means, we can now obtain both the brightness and the mass of this exoplanet. As a general rule, the more massive the planet, the more luminous it is.”

Beta Pictoris c is much brighter than Beta Pictoris b

In this case, however, the data on the two planets is somewhat puzzling: The light coming from Beta Pictoris c is six times fainter than its larger sibling, Beta Pictoris b. Beta Pictoris c has 8 times the mass of Jupiter. So how massive is beta Pictoris b? Radial velocity data will ultimately answer this question, but it will take a long time to get enough data: one full orbit for planet b around its star takes 28 of our years! Paul Molliere, who as a postdoc at MPIA is modeling exoplanet spectra, said:

“We used GRAVITY before to obtain spectra of other directly imaged exoplanets, which themselves already contained hints on their formation process. This brightness measurement of b Pictoris c, combined with its mass, is a particularly important step to constraining our planet formation models.”

Additional data might also be provided by GRAVITY+, the next-generation instrument that is already under development.

Provided by: Hannelore Hämmerle, Max Planck Society [Note: Materials may be edited for content and length.]

Follow us on Twitter, Facebook, or Pinterest