Since ancient times, the Chinese have paid special attention to family discipline and family education. Famous scholars in history, from the Song Dynasty (960-1279), the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), and on down to the Qing Dynasty (1636-1912), have all left advice for their family members based on their own experiences. There are also many forms of family letters and poems that focus on teaching children.

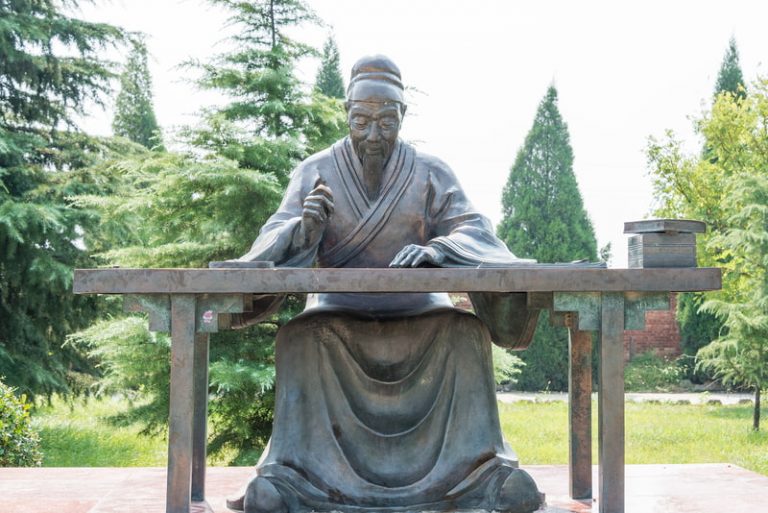

Yan Zhitui (531-591), a scholar of the Northern Qi Dynasty, wrote a compendium of his philosophy and advice for his sons known as The Family Instructions of Master Yan. In it, he warned his children and grandchildren not to be proud of their rank and cautioned them against being arrogant or lazy. It was also his hope that his descendants could remain a scholarly family that was part of the gentry, so he wrote a sprawling 20-part book with more than 40,000 words. The book was passed down in the family for the next 1,300 to 1,400 years and was revered by later generations.

Yan Zhitui’s painstaking efforts were not in vain. The Yan family’s children and grandchildren did indeed strive for excellence. His grandson, Yan Shigu, was a great scholar who wrote The Book of Han during the Tang Dynasty. Down to the fifth generation, one grandson, Yan Zhenqing, was a renowned scholar, and another, Yan Gaoqing, was a famous politician.

In the Qing Dynasty, Wang Chang, who served as the Secretary of the Da Li Temple, warned his children that when they saw profit, they should not forget righteousness and should not be greedy; that they should not be indifferent, deceitful, or show favor to others; that they should not be selfish or take advantage of others; and that they should be generous to others and should not do unto others what they did not want to have done to them.

The family precepts emphasize firstly “cultivating one’s moral character” and secondly, “family harmony,” which includes how to treat the elderly, children, wives, brothers, and servants. At the periphery of the harmonious family, there is instruction for fulfilling one’s duty to more distant relatives. Then, beyond the scope of dealing with relatives, there is instruction on how to be an official and fulfill one’s duty to the country. All this is included in the family precepts, which follow the principle of “cultivating one’s moral character, bringing one’s family into harmony, governing one’s country properly, and creating a peaceful world” as emphasized in the Confucian classic The Great Learning.

In terms of specific content, chapters on filial piety appear commonly in the family precepts of many families. Children and grandchildren are repeatedly admonished to work hard — not to show their personal value, but to honor the ancestors; while the purpose of doing more good deeds is to “accumulate virtue to bequeath to the children.”

The second most important topic for families after filial piety is how to be hardworking and frugal. The classic work on this subject is the Family Precepts of Sima Guang written by the high-ranking Song Dynasty official, Sima Guang. One bit of wisdom it imparts is: “It is easy to go from frugality to extravagance, and difficult to go from extravagance to frugality.”

Sima Guang knew that no matter how lucky the family, it would be impossible to produce someone who rose to a high rank in every generation, not to mention that there would be sons born who would exercise poor self-control and who could thereby ruin the family business established by their ancestors. Therefore, he said: “Every bowl of porridge or rice reminds us of the difficulties of acquiring them. Even half a strand of thread constantly reminds us of the struggles of making ends meet.”

Teachings in China were to gain wisdom, not name and fame

Excessive extravagance and luxurious habits are absolutely unacceptable. These are two widely recited lines from the Family Teachings of Zhu Zi. Even though the entire text is devoted to being hardworking and frugal, it does not approve of bequeathing generous wealth to future generations because: “A wise person who has more money will lose his will; a foolish person who has more money will increase his faults.” The only things to leave to children and grandchildren were the good virtues of honesty and frugality.

Another point emphasized in Family Teachings is “modesty and silence” — being careful in speech and action, generous and forbearing, and not causing trouble. What was most feared was that descendants would be proud and lazy, fight with others and exhibit cruelty, thus inviting resentment which would bring trouble to themselves and disaster to the family.

The virtue of “modesty and silence” can also be expressed as being careful in the selection of friends. Thus, if descendants in the family happen to be wealthy, they should avoid making friends with people whose chief interest is eating good food and drinking good wine and avoid associating with those who are treacherous, malicious, or who act in bizarre ways, so as to avoid being contaminated by their bad habits.

Among the many family precepts, although there is much written about “cultivating one’s character,” there is not so much written that encourages scholarly pursuits to advance oneself. Some distinguished founders of family teachings advised their children and grandchildren not to worry about fame, but to “cultivate and read,” holding these as the ideal goal. They believed that the purpose of reading the works of the sages was to learn how to be a good human being, not to use the knowledge to become a rich and powerful official.

The Complete Collection of Treasured Family Teachings written by Shi Chengjin during the Qing Dynasty also said that if parents teach their descendants to “hope for a successful future and expect wealth and honor,” they may end up as corrupt officials, ruining their families and lives and bringing shame to their ancestors. This is not because the descendants are unworthy, but because the parents taught them poorly.

Translated by Eva

Follow us on Twitter, Facebook, or Pinterest