The human brain is made up of around 86 billion neurons, linked by trillions of connections. For decades, scientists have believed that we need to map this intricate connectivity in detail to understand how the structured patterns of activity defining our thoughts, feelings, and behavior emerge.

Our new study, published in Nature, challenges this view. We have discovered that patterns of activity in our neurons are more influenced by the brain’s shape – its grooves, contours, and folds – than by its complex interconnections.

The conventional view is that specific thoughts or sensations elicit activity in specific parts of the brain. However, our study reveals structured patterns of activity across nearly the entire organ, relating to thoughts and sensations in much the same way that a musical note arises from vibrations occurring along the entire length of a violin string, not just an isolated segment.

Function follows form

We uncovered this close relationship between shape and function by examining the natural patterns of excitation that can be supported by the anatomy of the brain. In these patterns, called “eigenmodes,” different parts are all excited at the same frequency.

Consider the musical notes played by a violin string. The notes arise from preferred vibrational patterns of the string that occur at specific, resonant frequencies. These preferred patterns are the eigenmodes of the string. They are determined by the string’s physical properties, such as its length, density, and tension.

In a similar way, it has its own preferred patterns of excitation, which are determined by its anatomical and physical properties. We set out to identify which specific anatomical properties of it most strongly affect these patterns.

A tale of two brains

According to conventional wisdom, its complex web of connections fundamentally sculpts its activity.

This perspective views it as a collection of discrete regions, each specialized for a specific function, such as vision or speech. These regions communicate via interconnecting fibers called axons.

An alternative view, embodied by an approach to modeling brain activity called neural field theory, eschews this division of the organ into discrete areas.

This view focuses on how waves of cellular excitation move continuously through brain tissue, like the ripples formed by raindrops falling into a pond. Just as the shape of the pond constrains the possible patterns formed by the ripples, wavelike patterns of activity are influenced by its three-dimensional shape.

Comparing the two views

To compare the two views of the brain, we tested how easily the conventional, discrete view and the continuous, wave-based view can explain more than 10,000 different maps of its activity. The activity maps were obtained from thousands of functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) experiments as people performed a wide array of cognitive, emotional, sensory, and motor tasks.

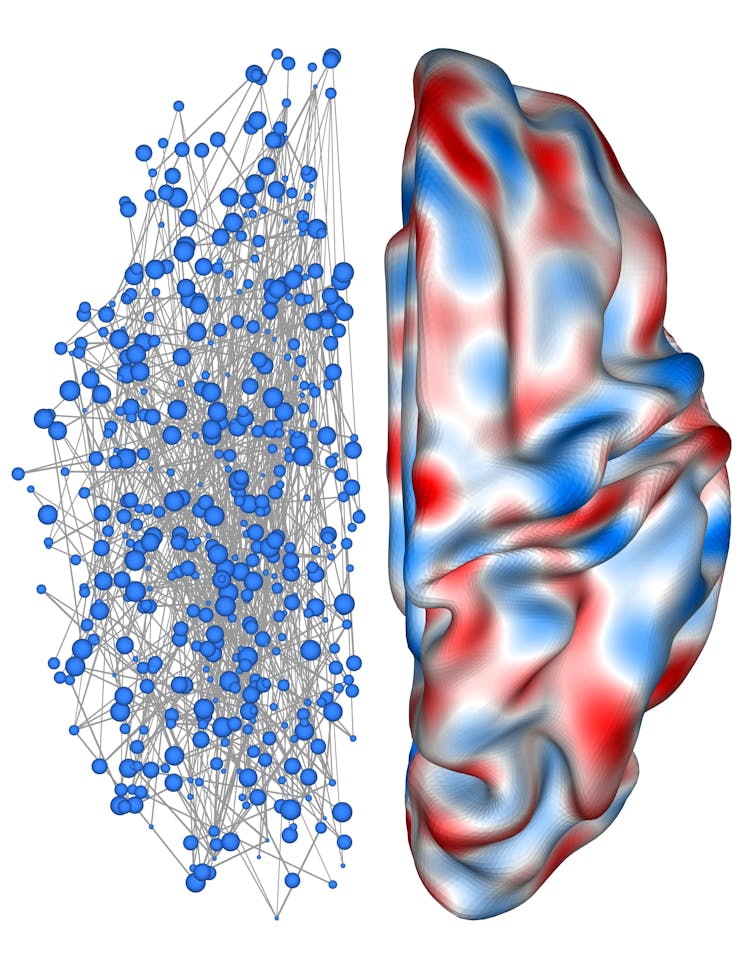

We attempted to describe each activity map using eigenmodes based on the brain’s connectivity and eigenmodes based on its shape. We found that eigenmodes of shape — not connectivity — offer the most accurate account of these different activation patterns.

Brain waves and icebergs

We used computer simulations to confirm that the close link between its shape and function is driven by wavelike activity propagating throughout it.

The simulations relied on a simple wave model that is widely used to study other physical phenomena, such as earthquakes and ocean currents. The model only uses the shape to constrain how the waves evolve through time and space.

Despite its simplicity, this model explained brain activity better than a more sophisticated, state-of-the-art model that tries to capture key physiological details of neuronal activity and the intricate pattern of connectivity between different regions.

We also found that most of the 10,000 different brain maps that we studied were associated with activity patterns spanning nearly the entire organ. This result again challenges the conventional wisdom that activity during tasks occurs in discrete, isolated regions of it. In fact, it indicates that traditional approaches to mapping may only reveal the tip of the iceberg when it comes to understanding how it works.

Together, our findings suggest that current models of brain function need to be updated. Rather than focusing solely on how signals pass between discrete regions, we should also investigate how waves of excitation travel through it.

In other words, ripples in a pond may be a more appropriate analogy for large-scale brain function than a telecommunication network.

A new approach to brain mapping

Our approach draws on centuries of work in physics and engineering. In these fields, the function of a system is understood with respect to the constraints imposed by its structure, as embodied by the system’s eigenmodes.

This approach has not been traditionally used in neuroscience. Instead, typical brain mapping methods rely on complex statistics to quantify activity without any reference to the underlying physical and anatomical basis of those patterns.

The use of eigenmodes offers a way to use physical principles to understand how diverse patterns of activity arise from brain anatomy.

Our discovery also offers immediate practical benefits, since eigenmodes of brain shape are much simpler to quantify than those of connectivity.

This new approach opens possibilities for studying how brain shape affects function through evolution, development, aging, and in brain disease.

James Pang, Research Fellow in Psychology, Monash University and Alex Fornito, Professor of Psychology, Turner Institute for Brain & Mental Health, Monash University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Follow us on Twitter, Facebook, or Pinterest