Whenever there is warfare, there are espionage activities. The means of carrying out spying on enemy forces have changed over time. Nowadays, advanced technologies and devices are being used for espionage worldwide, including drones and spy satellites. In ancient ages, animals and birds were also deployed for such needs. However, not many people know that during WWI, knitting was used as a means of espionage. Innocent-looking women, including the elderly, conveyed secret messages through specific acts of knitting fabrics. The soldiers interpreted these to figure out the movements and activities of enemy troops.

In her book Stitches in Time, Lucy Adlington wrote about the stitching-based message practice that became popular during WWI. She wrote about an article published in the UK Pearson’s Magazine in late 1918. She wrote: “When the German authorities carefully unraveled such a sweater, the story went, they found the wool thread dotted with many knots. By marking a vertical door frame with the letters of the alphabet, spaced an inch apart, the knots could be deciphered as words by measuring the yarn along this alphabet and marking which letters the knots touched.”

Knitting to convey a secret message was a safer practice than trying out other more conventional methods for espionage. A lot of women used to stitch socks or hats for soldiers. In many countries, knitting was used for espionage. The activity was prohibited in the UK, yet the British Secret Intelligence Service deployed spies who knitted to convey messages in the enemy’s presence without being discovered. Kathryn Atwood writes about Madame Levengle in Women Heroes of World War I: “Her children used to jot down the codes conveyed by the lady tapping her heels while knitting. The kids pretended they were doing school assignments. This was done in the presence of a German marshal.”

Knitting to convey military information has been used in several wars

The practice of using knitting to convey critical information on enemy troop movements and developments continued during WWII. It was used a lot by the Belgian Resistance in that period. A U.S. spy named Elizabeth Bently used to indulge in knitting. In fact, knitting was also used extensively during the American Revolutionary War.

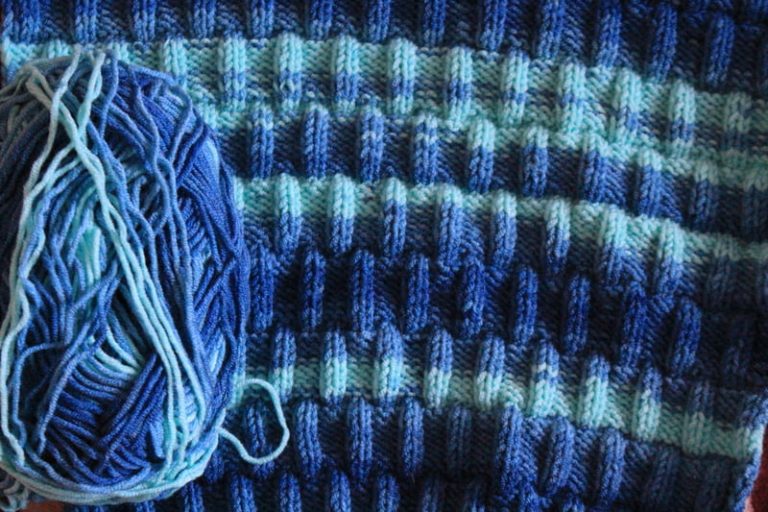

Stitching is used to convey helpful war and enemy activity-related messages, which is known as steganography. The stitching pattern was devised to fool the enemy. Melissa Kemmerer, who set up the Nomadic Knits knitting and culture magazine, says: “Knitting is made up of different stitches, the most common of which is the knit and purl; at its simplest, relatable to binary code. Knit stitches are flat and resemble the letter ‘V’, while purple stitches are horizontal bumps.”

The spies used patterns like dashes and dots, numbers, or text in fabric to pass the secret messages. Kemmerer adds: “Knit and purl stitches are regularly used together in patterns to create a variety of common textures (picture the ribbing on the hems and cuffs of a sweater), and the odd purl bump hidden in a pattern of knit stitches could easily be overlooked, or if noticed, assumed to part of the intended patterning. Even when more noticeable stitches were used to encode a message into the garment, it would appear to the uneducated eye to be simply a mistake.”

While long-distance communications technologies flourished after WWI, knitting remained effective and safe. It was also a good cover. A female spy could resort to knitting in broad daylight without alarming anyone. Belgian intelligence agents used many elderly women for this purpose. The women passed on updates on Imperial Germany’s train movements.

Many brave women risked their lives while helping out the allied forces through knitting. Phyllis Latour Doyle, a clever and courageous British spy, parachuted into Normandy, and she utilized knitting to pass on secret messages about the Nazi forces to the British troops. She fooled the suspicious German intelligence officers with aplomb.

Follow us on Twitter, Facebook, or Pinterest