As William Blakney stated about Confucius in his 1955 translation of the Tao Te Ching:

“It is no accident that China’s great moral innovator Confucius was a gregarious man who haunted capital cities, accompanied by disciples, pleading for a chance to set things right. Nor is it an accident that an important and original expression of the great mysticism of all time was conceived in some of China’s renowned valleys.”

The writer continued to explain that “proposals of morals receive the most fertile response in those areas where people are closely pressed together and life requires general agreement on its conduct. In China, people have always lived closely pressed together, so they are moral, and Confucius has been their representative.” Mysticism still survives in China, but rather on the periphery of life where there is room for it to flourish.

After so many decades of preoccupation with things other than tradition and the classics, Chinese people are slowly rediscovering much of their time-honored heritage, including that of Confucius. Ancient writings tell of him holding the view that he had been given divine inspiration to teach moral excellence, but that he would never say more than he was convinced he knew. He readily acknowledged that the virtues he possessed were not of his own doing, but a divine gift. He eventually passed on his inspirations in Analects, classical sayings attributed to him. These writings arose partly out of the immense evils that had befallen the Chou Dynasty.

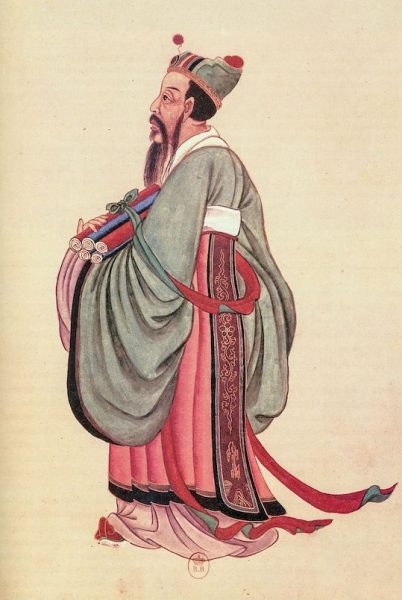

After so many decades of preoccupation with things other than tradition and the classics, the Chinese people are slowly rediscovering much of their time-honored heritage, including that of Confucius. (Image: via Wikimedia Commons)

Ritual was of utmost importance to Confucius

The Confucian way of then looking at life placed great emphasis on proper moral conduct, rituals, and intercessory prayer, but realized at the same time that unless these prayers were within the plans of gods, they were useless. Ritual, of all these, was of foremost importance to Confucius. He looked at rituals as the orderly interchange between man and the gods. This was closely followed by proper moral conduct.

The combination of rituals and proper moral conduct led to a specific system of etiquette, eventually for the whole of civilization during that era. Scores of Chinese people observe at least a small measure of this to the present day. He also cautioned that morals, represented by certain expressions of etiquette, must be the root of civilization, and that there is an orderly, humane way of existence, displaying inner goodness, those being representative qualities of a superior human being.

During the lifetime of Confucius, the way in which people were expected to live a proper life eventually led to 3,000 rules of conduct one needed to master in order to achieve a preferred civil service position. He began to realize that his system was not flawless, because anyone having to learn that many rules had scant time to devote to improving one’s moral character. When asked who ought to be promoted to a superior civil post, he was said to have replied to promote those whom you know to be good.

Although he was not an intellectual person, and was not a systematic thinker, according to history books, he pronounced that filial piety was to be of prime importance, [later becoming an obsession for the people] and that one would achieve a rise in one’s spiritual level by honoring The Ancients.

Deeper spiritual excitement, however, had to be found outside Confucian orthodoxy. The legacy of Confucius for China, nevertheless, is the dissemination of his doctrine of the moral nature of man, and the massive spirit of humanism that developed in China in subsequent centuries. His ways have endured for so long because they have strongly appealed to the common-sense way of life of the Chinese people.

Follow us on Twitter, Facebook, or Pinterest