Physicists at the University of Warwick have published new research in the journal Science that could literally squeeze more power out of solar cells by physically deforming each of the crystals in the semiconductors used by photovoltaic cells.

The paper, entitled the Flexo-Photovoltaic Effect, was written by Professor Marin Alexe, Ming-Min Yang, and Dong Jik Kim, who are all based in the University of Warwick’s Department of Physics.

The Warwick researchers looked at the physical constraints on the current design of most commercial solar cells that place an absolute limit on their efficiency.

Most commercial solar cells are formed of two layers, creating at their boundary a junction between two kinds of semiconductors — p-type with positive charge carriers (holes which can be filled by electrons) and n-type with negative charge carriers (electrons).

When light is absorbed, the junction of the two semiconductors sustains an internal field, splitting the photo-excited carriers in opposite directions, and generating a current and voltage across the junction.

Without such junctions, the energy cannot be harvested and the photo-exited carriers will simply quickly recombine, eliminating any electrical charge.

That junction between the two semiconductors is fundamental to getting power out of such a solar cell, but it comes with an efficiency limit.

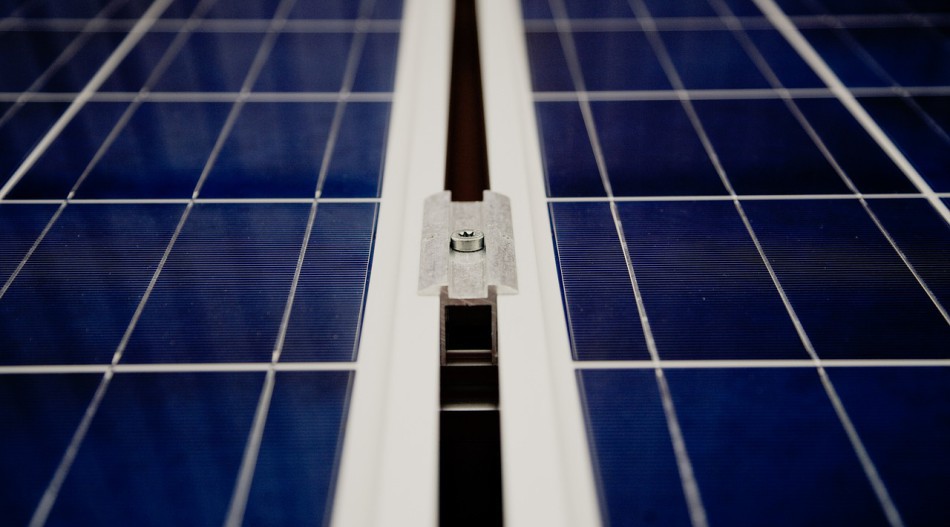

Artist’s impression of squeezing more power out of solar cells by physically deforming each of the crystals in the semiconductors used by photovoltaic cells. (Credit: University of Warwick / Mark Garlick)

This Shockley-Queisser Limit means that of all the power contained in sunlight falling on an ideal solar cell in ideal conditions, only a maximum of 33.7 percent can ever be turned into electricity.

There is however another way that some materials can collect charges produced by the photons of the sun or from elsewhere.

The bulk photovoltaic effect occurs in certain semiconductors and insulators where their lack of perfect symmetry around their central point (their non-centrosymmetric structure) allows generation of voltage that can actually be larger than the band gap of that material (the band gap being the gap between the valence band highest range of electron energies in which electrons are normally present at absolute zero temperature and the conduction band where electricity can flow).

Unfortunately, the materials that are known to exhibit the anomalous photovoltaic effect have very low power generation efficiencies, and are never used in practical power-generation systems.

Commercial solar cells manipulated to be more efficient

The Warwick team wondered if it was possible to take the semiconductors that are effective in commercial solar cells and manipulate or push them in some way so that they too could be forced into a non-centrosymmetric structure and possibly therefore also benefit from the bulk photovoltaic effect.

For this paper, they decided to try literally pushing such semiconductors into shape using conductive tips from atomic force microscopy devices to a “nano-indenter” which they then used to squeeze and deform individual crystals of Strontium Titanate (SrTiO3), Titanium Dioxide (TiO2), and Silicon (Si).

They found that all three could be deformed in this way to also give them a non-centrosymmetric structure and that they were indeed then able to give the bulk photovoltaic effect. Professor Marin Alexe from the University of Warwick said:

“Extending the range of materials that can benefit from the bulk photovoltaic effect has several advantages: It is not necessary to form any kind of junction; any semiconductor with better light absorption can be selected for solar cells, and finally, the ultimate thermodynamic limit of the power conversion efficiency, so-called Shockley-Queisser Limit, can be overcome.

“There are engineering challenges but it should be possible to create solar cells where a field of simple glass based tips (a hundred million per cm2) could be held in tension to sufficiently de-form each semiconductor crystal.

“If such future engineering could add even a single percentage point of efficiency it would be of immense commercial value to solar cell manufacturers and power suppliers.”

Provided by: University of Warwick [Note: Materials may be edited for content and length.]

Follow us on Twitter, Facebook, or Pinterest