People have been fascinated by dreams for eons. You’ve probably asked yourself, why do I dream? And do they have any biological functions?

How we can generate images from a sleeping brain has also confounded philosophers and scientists for centuries. One of the problems facing research into dreams has constantly been gaining access to people’s dreams.

But in 2013, researchers from ATR Computational Neuroscience Laboratories in Kyoto, Japan, made a significant breakthrough in dream research and analysis. Yukiyasu Kamitani, the lead researcher, and his colleagues said they had found a way to glimpse what you’re dreaming about.

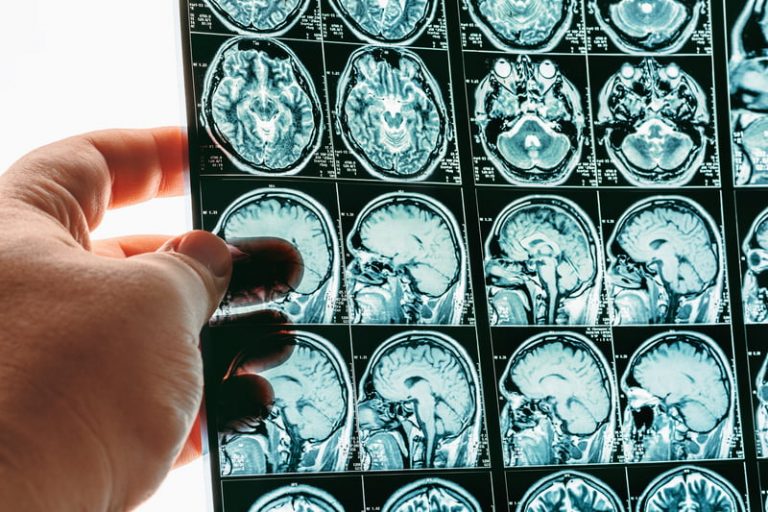

The team used fMRI scans to predict what the participants were dreaming about in the early stages of sleeping.

“Our results show that we can predict what a person’s seeing during dreams,” said Kamitani.

‘Reading’ dreams using brain waves

This study’s first phase monitored three participants’ brain activity using electroencephalography (EEG) and fMRI. Once the researchers saw the EEG pattern of brain waves associated with dreaming, they woke the participant and asked them to recount what they had dreamed about.

This routine was repeated more than 200 times, and the scientists used the results to build a “dream” database. In this database, they noted everything from the dreams, from mundane things like keys to the surreal, like dining with a famous actor.

“Many of them were just about daily life in the office,” Kamitani said.

The researchers then grouped objects into categories such as “female,” “car,” “computer,” “male,” and more. For instance, houses, hotels, or buildings were in the “structures” category.

Decoding the dreams

In the second part, the scientists developed a visual imagery decoding program. They trained the decoder to categorize patterns of brain activity obtained from the same three participants while awake and watching hundreds of images on a screen. Afterward, the researchers could input a pattern of brain activity into the program and let it predict which image a participant was thinking about.

Similar studies have focused on deducing what people are thinking when awake. But Kamitani and his team went beyond that and used brain activity obtained when the participants were dreaming. The decoder enabled them to identify the object that a person had dreamed about.

However, it’s worth noting that while the program could predict the object in the dream, it did not show the whole unfolding narrative. For instance, it could indicate you’ve dreamed about a man, but not a man in a dungaree with an axe chasing you.

“The results suggest that it may be possible to read out dream contents even when you don’t remember just by looking at brain activity,” Kamitani said.

Dream reconstruction

As mentioned, the program could not decode color, emotion, or actions in the dream. Also, the program had to be tweaked for every participant, meaning you can’t have a single dream-reading machine for everyone. Still, it’s a significant step, since it could predict the object in the dream with 60 percent accuracy.

Other scientists say this breakthrough could help understand the nature and importance of dreams. They also believe it could help them understand human consciousness in the long run.

Jack Gallant, a neuroscientist, believes that understanding our dreams’ mystery is arduous. Gallant is a neuroscientist at the University of California, Berkeley, and a pioneer in decoding mental states from brain scans.

“It took just a huge amount of non-glamorous work to do this, and they deserve big props for that,” Gallant said.

“There’s the classic question of when you dream, are you actively generating these movies in your head, or is it that when you wake up, you’re essentially confabulating it? What this shows you is at least some correspondence between what the brain is doing during dreaming and what it’s doing when you’re awake,” he added.

Implications of dream research

This study investigated dreams in the early stages of sleep, but the researchers said they would look at dreams in the deeper REM sleep next. This is when more vivid dreams occur, and they want to see if scans from this sleep phase can help them decode emotions, colors, smells, and actions from people’s dreams.

Dream research and analysis can help scientists nail down the biological or psychological importance of dreaming. Such studies can also help them find remedies for people with insomnia or post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

At the moment, scientists can’t reconstruct your dreams like a movie, but Kamitani believes understanding them is a good start.

“Knowing more about the content of dreams and how it relates to brain activity may help us to understand the function of dreaming,” he says.

Follow us on Twitter, Facebook, or Pinterest