Architecture is a discipline where art meets mathematics (engineering). Architects essentially blend these two sides, making architecture interesting for many people.

But is there a one-size-fits-all design philosophy for architects? Why is one building more beautiful than another? Can architects create a building that will be universally beautiful, and what would be the characteristics of such a building?

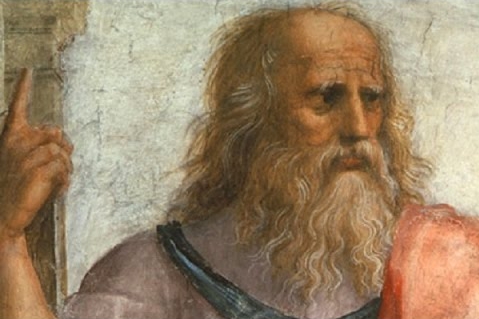

This article explores how the great Western thinker Plato has shaped architecture. As the saying goes: “Architects are from Plato, while engineers are from Aristotle.”

A lesson from the past

Humans have always loved beautiful things, and ancient Greeks studied natural forms, including our human form, to try and copy the “creator.” Plato was among the first philosophers to ask himself why people love beautiful things. He said that beautiful things tell us the truth about the good life. For Plato, beauty and truth were not two distinct properties.

One of Plato’s main ideas for a good life was understanding beauty. He believed our different tastes as humans come because we are corrupted copies of an actual or pure human form. That is, there is a singular human archetype, and we are imperfect copies — that’s why we can’t all find the same thing beautiful.

According to Plato, we only find beauty when we unconsciously see in something the things that we miss in our lives. So if architects can discover the elusive human archetype, they could theoretically create buildings that are universally appealing to all our shadowy forms. Once found, every building, from churches and homes to marketplaces, would be beautiful to everyone.

Since this possibility was suggested, architects have been trying to capture the human essence and create something everyone loves.

The Vitruvian man

Marcus Vitruvius Pollio, a Roman architect and engineer during the 1st century B.C., known for his multi-volume work titled De Architecture, described the proportions of the human body. His proportional drawings revolved around Plato’s idea of a perfectly built man. This human archetype extends his arms and feet and fits precisely into the most balanced geometrical figures: a circle and a square.

Vitruvius may not be the first architect, but James Anderson and Benjamin Franklin described him as “The Father of all true Architects to this Day.” Vitruvius truly believed that a building based on the geometry of the abovementioned harmonious figure would have universal appeal. It gives architects an objective scale in the world of subjective human preferences.

During the Renaissance, Leonardo da Vinci’s sketch immortalized that harmonious figure described by Vitruvius 500 years earlier. Today, we know it as the Vitruvian man.

The Renaissance architects

As mentioned, Plato thought proportions could be universally beautiful because they are found in nature and express the “truth.” We see the application of this philosophy in Renaissance architecture. Architects in this era were ardent believers of “perfect circles and squares,” thanks to the newfound love for the Greek mathematical representation of the world.

Also, there was the Christian belief that “Man as the image of God embodied the harmonies of the Universe.” So architects in this era thought that the representation of beauty was in numbers, such as the Fibonacci sequence (the Golden Ratio). So should architects uphold the “Golden Ratio” because it’s found in nature? Is the Fibonacci sequence the human archetype that Plato thought of millennia ago?

Has anything changed in modern architecture

Like those before him, the average modern architect wants a universally beautiful building that stands the test of time. Architects like the celebrated Le Corbusier, who came nearly 500 years after the Renaissance, still looked to produce buildings that satisfy the human archetype.

Le Corbusier devised The Modulor, which he describes as a “range of harmonious measurements to suit the human scale, universally applicable to architecture and mechanical things.” It shows that as modern architects try to extricate themselves from past beliefs, they still find themselves subject to human judgment — as an architect, you have to appeal to people’s tastes and preferences.

However, some architects feel marriage to this philosophy can limit human imagination. Plato thought that human beauty could be objective. Architects who find these universal proportions can achieve universal beauty and “truth.” However, some modern architects say that as much as you try to be objective, people will always be subjective.

The early modern architect Louis Sullivan stated: “Form follows function.” In short, modern buildings have to be beautiful, no doubt. Still, architects also have to think about the purpose of this building and consider things like wheelchair accessibility and environmental conditions.

Aristotle’s approach

Plato may have seen beauty and “truth” as related, but Aristotle was more scientific (rational) in his approach. As we said earlier, “engineers are from Aristotle” and mostly have functionality in mind before everything else.

So who should future designers turn to for inspiration: Aristotle or Plato? Is there a universal way to appeal to everyone, or should our structures serve the purpose they are meant to serve?

Takeaway

Michael Chusid, an architect and construction specifier, says: “The best architects have their heart in Plato and their head in Aristotle.” This is not an easy balance to maintain. Still, architects have to satisfy the rationality of Aristotle and strive to create a structure that will be beautiful in the eyes of everyone.

Follow us on X, Facebook, or Pinterest