Did you know that the original Roman calendar system only had 10 months? And why does the ninth month in our calendar have the name of the seventh month in the Roman calendar? It might sound strange, but when the Romans first created their system, it didn’t align with the lunar or solar year. Instead, it was all about agriculture and war. Let’s take a fun and fascinating look at how the Roman calendar came to be, why it only covered part of the year, and what other ancient cultures have to say about the concept of time.

Why did the Roman calendar system only have 10 months?

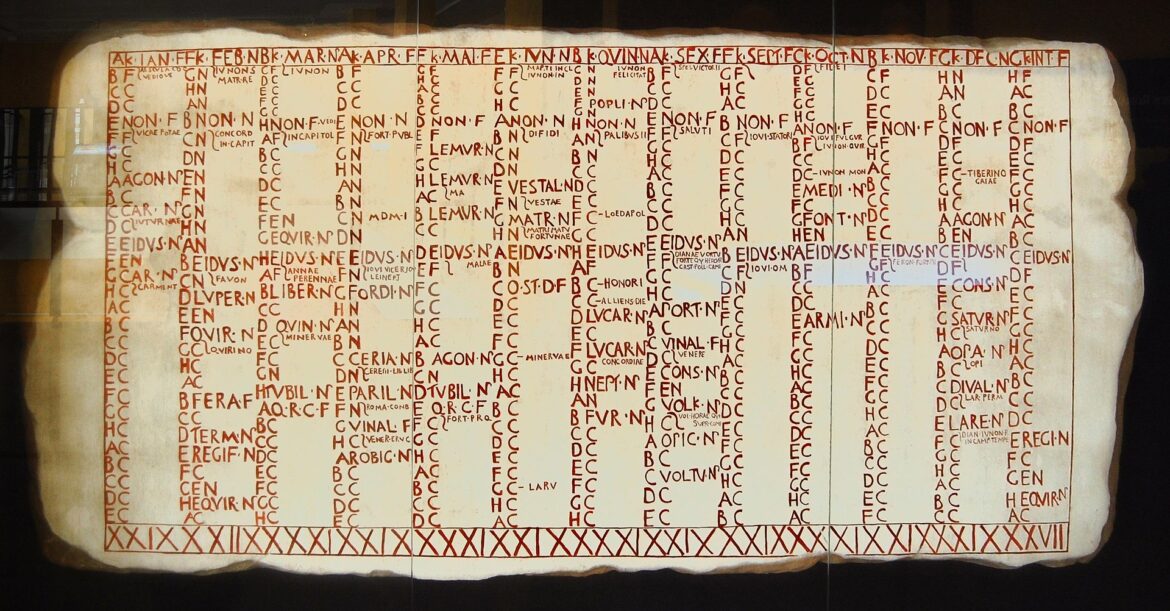

Some 200 fragments of Roman calendars have been found so far, collectively known as Fasti. The Romans borrowed parts of their earliest known calendar from the Greeks. The calendar consisted of 10 months in a year of 304 days. The Romans seem to have ignored the remaining 61 days, which fell in the middle of winter. Romulus, the legendary first ruler of Rome, is supposed to have introduced this calendar in the 700s B.C.E.

Why so short? For the Romans, the year only needed to cover the “active” months — when farmers could work the land and soldiers could go to war. The cold, unproductive winter months were ignored and left unassigned, which seems bizarre today, but it worked for them.

So, the year kicked off in March (Martius), named after Mars, the god of war — fitting for a society that lived and breathed combat. It ended in December (Decem), which means “ten,” wrapping up the harvest season. Between these, you had April, May, June, and so on, each month having its significance. The idea of keeping a calendar just for the productive part of the year shows how practical (and a bit unconventional) the early Romans were.

What’s the story behind the month names?

Some Roman month names make a lot of sense — at least initially. March was named after Mars, April was likely about opening and blossoming (the Latin “aperire” means “to open”), May honored Maia, a goddess of spring, and June was named for Juno, the queen of the gods. But then, things got pretty straightforward.

Quintilis, or “fifth,” and Sextilis, or “sixth,” followed, then September (seven), October (eight), November (nine), and December (ten). Easy, right? However, when January and February were added later, all these numbers became out of sync with the months they represented. So now, September (meaning “seven”) is our ninth month, and December (“ten”) is our twelfth. Blame the shifting calendar reformations for that!

How did the Roman calendar evolve?

The 10-month system had some flaws — like being way out of sync with the solar year. Enter King Numa Pompilius, Rome’s second king, who thought it was time to shake things up. Around 713 BCE, he added January and February to bring the total to 12 months and tried to make the year more reasonable. Even so, his calendar ended up with 355 days, which meant it still needed adjustments to stay in line with the seasons. Sometimes, they’d throw in an extra month called Mercedonius to realign things, making it a total calendar mess.

The Romans finally got severe about syncing with the solar year when Julius Caesar came along. In 46 BCE, he introduced the Julian calendar, which gave us a 365-day year and a leap year every four years. This was a game-changer, bringing the Roman year in line with the solar cycle, and it’s the basis of the calendar we use today.

What did other cultures use for calendars?

While the Romans wrestled with their odd calendar, other ancient civilizations had some fascinating ideas. The Mayans, for instance, were brilliant astronomers who loved the number 13. Their Tzolk’in calendar had 260 days divided into 20 periods of 13 days, reflecting the sacred nature of 13 in their culture. Even though they didn’t have a traditional 13-month calendar, they recognized the power of this number in their religious and celestial practices.

The Egyptians also had a unique way of keeping time. They had 12 months of 30 days each, plus five extra days added at the end of the year to make 365. These extra days were considered sacred, and the Egyptians even had a lunar calendar that required occasional adjustments, hinting at an additional month.

The Chinese calendar, which is still used for festivals, is lunisolar, which combines the moon’s and the sun’s cycles. About every three years, the Chinese calendar adds a 13th month to sync with the solar year. This system highlights how humans have always tried to balance nature and time.

What’s the deal with the turtle shell?

Here’s where things get interesting. Have you ever looked closely at a turtle shell? Many indigenous cultures, including some Native American tribes, see it as a representation of the natural calendar. The shell has 13 large scutes(sections), matching the 13 full moons in a year. Around the edge are 28 smaller scutes, similar to the number of days in a lunar month. The turtle, symbolizing stability and connection to the Earth, reminds us of the profound relationship between nature and time.

Key takeaways

- The original Roman calendar was more about practicality than astronomy and focused on the agricultural and military seasons.

- The names of the months tell a story of mythology and counting, but later reforms threw them off-kilter.

- Ancient cultures like the Mayans, Egyptians, and Chinese each had unique approaches to time, some even recognizing 13 cycles.

- The turtle shell as a natural timekeeper shows how humans have always looked to nature for guidance.

Final word

Our calendars are more than just a way to keep track of days — they’re a window into how ancient civilizations viewed the world. The Romans built their system around the needs of everyday life, while other cultures saw deeper connections to the moon, the sun, and even animals like the turtle. It’s a reminder of how humanity has always sought to understand and organize the passing of time, balancing practicality with the mysteries of the cosmos. Maybe it’s time we think more about the rhythms of nature in our fast-paced world. Who knows? Perhaps we can learn a thing or two from those ancient timekeepers.

Follow us on X, Facebook, or Pinterest