Living between 1870 and 1966, Maxfield Parrish grew up in a time of aesthetic optimism in the United States. For illustrators, architects, and designers of any sort in this era, the aesthetic grammar of neo-classical and Victorian styles was in vogue. These styles used the same visual language passed down from Hellenic Greece over 2,000 years ago.

Urban spaces were entrusted to artisans whose foundations and ethos in beauty reflected what was understood in the Socratic roots of Western civilization as the universal order — truth, goodness, and beauty. The arts reflected and revealed the truth of creation, beauty transported us to the truth, and goodness was the temperament and characteristic of the universe. Thus, the cities, parks, and streets were attractive and inviting places that harmonized with virtue. Nearly every product and advertisement in society had been adorned with images that radiated beauty. When the movers and shakers in society highlighted dignified beauty, it created a more harmonious and peaceful atmosphere.

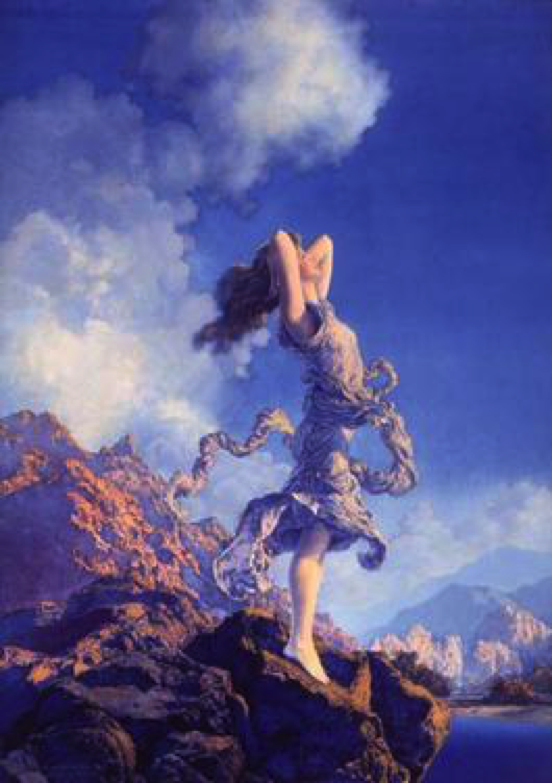

‘Ecstasy,’ Maxfield Parrish, 1930, Oil on Panel. Edison Mazda Lamp calendar illustration. (Image: via Public Domain)

“When a man has been thus far tutored in the lore of love, passing from view to view of beautiful things, in the right and regular ascent, suddenly he will have revealed to him, as he draws to the close of his dealings in love, a wondrous vision, beautiful in its nature; and this, Socrates, is the final object of all those previous toils… Beginning from obvious beauties, he must for the sake of that highest beauty be ever climbing aloft, as one the rungs of a ladder, from one to two, and from two to all beautiful bodies; from personal beauty he proceeds to beautiful observances, from observance to beautiful learning, and from learning at last to that particular study which is concerned with the beautiful itself and that alone; so that in the end he comes to know the very essence of beauty.” (Plato, Symposium, from Awakening Wonder: A Classical Guide to TRUTH, GOODNESS & BEAUTY, by Stephen R. Turley, Ph.D.)

Maxfield Parrish’s beautiful world

In modern terms, designing advertisements may seem like an uninspiring necessary task to hook the masses into buying their products. It may resemble a dance between a Freudian social engineer, testing the effect of certain colors and symbols on the psyche, and a graphic designer, who interprets and, through several board meetings later, pitches designs meant to elicit the most stimuli from customers.

Rewind several decades earlier, everything had to be dignified, moral, and above all, stunningly beautiful to fit in with the tastes of people and their sense of beauty at the time. Of the guidelines many illustrators had to follow in designing advertisements, those rules were about all there were.

‘Cleopatra,’ Maxfield Parrish. His series of images for Crane’s Chocolates, which decorated their packaging and boxes with oriental themes. Many people collected them for the artwork. (Image: via Public Domain)

The partnership between Maxfield Parrish and the Edison-Madza company, later to become General Electric, is an example of how industry branded itself in the past. Maxfield Parrish painted illustrations that went on many of their advertisements, the most famous being Ecstasy, an image designed for Edison-Mazda’s calendar. Refined beauty had been used to attract customers and promote a wholesome image of the company.

Following the phenomenal success of one of his most famous paintings, “Daybreak,” completed in 1922, many companies were climbing over each other to have Maxfield Parrish illustrate for them.

Maxfield Parrish’s popular ‘Mary, Mary, Quite Contrary’ illustration featured on Ferry’s Seeds bags. (Image: Public Domain)

Anything with his illustrations on them outsold other products. The public adored his work. Many people collected, stored, and framed advertisements by Maxfield Parrish. One in four households in the United States owned one of his prints. Maxfield Parrish stated of his works: “I am a commercial artist, who, ever since his beginning, has made his living by having his work reproduced. People who like attractive pictures are going to cut them out and possibly frame them no matter in what form, illustrations in books, in magazines, calendars, etc.”

‘A Girl with Elves,’ Maxfield Parrish, Lithograph. Djer-Kiss beauty products ad in the ‘Ladies’ Home Journal’ in 1918. (Image: via Public Domain)

Many illustrators in the golden age of illustration in the United States, including Norman Rockwell, J.C Leyendecker, Howard Pyle, Violet Oakley, and Harrison Fisher, gained celebrity status. They enjoyed the same recognition as the old masters in the past in fine art and architecture; this in large part was due to advances in printing. Illustration Art Solutions, an illustration publication, stated: “The trigger that brought about the Golden Age of Illustration was the introduction around 1880 of photo-mechanical engraving that enabled books and magazines to reproduce artwork with much greater fidelity than in the past… The distinction between commercial and fine art was blurred or non-existent. Books and magazines provided lucrative markets for an illustration that attracted and rewarded the most talented, skilled artists. As a result, illustrators produced a prodigious quantity of art that influenced popular culture and fashions.”

While Europe leaned toward impressionist and modern styles in art starting in the mid-1800s, the United States held on to more traditional aesthetics into the 1940s and 50s. Illustrators like Maxfield Parrish, who followed the traditional, academic lineage in art, still remained relevant and played an integral role in the ethos of the United States and informed and shaped public perception of beauty.

Written by Timothy Gebhart

Follow us on X, Facebook, or Pinterest