If you were to find someone else’s money lying on the ground, would you keep it? For people living in the modern world, the question often triggers hesitation rather than certainty. The pull between self-interest and conscience can feel complicated, and acts of simple honesty are sometimes dismissed as naïve or outdated. Yet in traditional China, such moments were often understood as tests of character — ones believed to shape a person’s future in ways both visible and unseen.

Waiting in the cold for a stranger

During the Ming Dynasty, in Anlu County of De’an Prefecture in what is now Hubei Province, there lived a scholar named Gao Chong. In the winter of 1525, during the Jiajing reign, Gao was recommended as a xiaolian — a candidate recognized for filial piety and upright conduct — and sent to the capital to sit for the imperial examinations.

As Gao traveled north with his attendant, the two stopped overnight at an inn. Before dawn the following morning, they resumed their journey. Along the road, they noticed a cloth bundle lying on the ground. The attendant picked it up and, weighing it in his hands, realized it was heavy. Gao immediately dismounted, led his horse aside, and sat beneath a large tree to wait for the owner.

The northern wind cut sharply through their clothes. Unable to endure the cold, the attendant tried to persuade him to leave. “Master,” he said, “it’s freezing, and we don’t even know who lost this bundle. Our travel funds are nearly gone — why suffer like this?” Despite repeated urging, Gao refused to move.

Returning what was never his

Not long afterward, a man approached, barefoot and poorly clothed, his hair unkempt, murmuring anxiously that his silver was gone. Gao stepped forward at once. “Have you lost your money?” he asked. “It hasn’t been lost — it’s with me.”

The man, close to despair, explained that he owed the government land tax. A severe drought had left his fields barren, and under a system that demanded payment regardless of circumstance, he had been driven to sell his two children into servitude — placing them in other households in exchange for fifty-five taels of silver — so that the debt could be paid. In the darkness and panic of the night, he had misplaced the bundle and believed all hope was lost.

Gao asked him to open the package and count its contents. The silver was intact, not a single tael missing. Overcome with emotion, the man wept and insisted on giving Gao half the money in gratitude. Gao refused. The man then led Gao’s horse for dozens of miles, unwilling to part. Later, after learning Gao’s name, he prayed for him morning and evening.

A career shaped by integrity

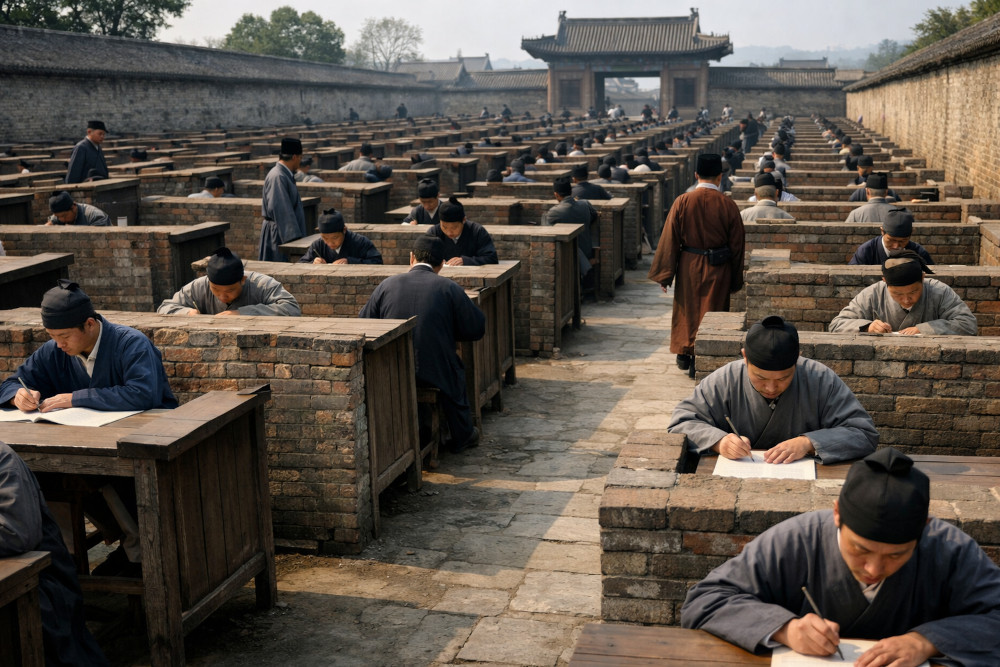

The following year, Gao Chong passed the imperial examinations and earned the jinshi degree, the highest scholarly qualification in the imperial system. He went on to serve as a magistrate in several counties, gaining a reputation for integrity and compassion. During a severe drought, he knelt in prayer beneath the blazing sun until rain finally fell.

His career advanced steadily, and he eventually rose to a high provincial post. One of his sons was admitted to the Imperial Academy, and all four sons lived long lives. Three became court officials, while another attained the rank of prefect. Even his grandchildren later held government positions.

When honesty and deceit meet the examination hall

A contrasting story from the Qing Dynasty illustrates how similar choices could lead to very different outcomes.

During the Jiaqing era, in Pinghu County, Zhejiang, lived a scholar named Xu Shifen. He had a cousin, Xu Shifang, with whom he prepared for the provincial examinations. Accounts of their experience differ slightly, but both center on an act of lost property and the choices that followed.

In one version, the two men discovered a woman’s bundle in their lodgings, filled with gold and silver jewelry. Xu Shifen warned his cousin not to covet such unexpected wealth and urged him to safeguard the bundle until its owner returned. Xu Shifang agreed in words, but after Shifen left, he secretly kept the jewelry and later lied to conceal what he had done.

Another account describes the two men encountering a woman at a temple who had just borrowed money to purchase ginseng for her ailing husband. In her haste, she left behind a bundle containing more than twenty taels of silver. Xu Shifang insisted on taking it. Unable to persuade him otherwise, Xu Shifen borrowed money from others and returned the full amount to the woman himself.

Both men later entered the same examination hall. After completing his essay, Xu Shifen felt dissatisfied and abandoned hope of success. On the eve of the results being posted, however, Xu Shifang’s paper was selected. As an examiner began writing his name on the list, the candle beside him suddenly flared, burning off a corner of the paper just after the first stroke of the character shi had been written.

The examiners debated what to do. Some suggested that such an omen reflected wrongdoing. Others argued that the list had already been written and could not be altered. Finally, a senior official decided that the name could simply be washed off and rewritten. A spare examination paper was brought forward. When it was opened, the examiners discovered it belonged to Xu Shifen.

Relieved, they laughed and said there was no need to rewrite anything after all — only to add the character fen beneath the existing stroke. In this way, Xu Shifen passed the examination, while his cousin did not.

Stories like these endure not because they promise reward or punishment from unseen forces, but because they expose how character operates under pressure. When people act honestly in moments that offer easy gain, they preserve trust — something no legal system or examination can replace. When they do not, the damage often surfaces in ways they never anticipated. Whether in an imperial examination hall or ordinary life, integrity shapes outcomes not through miracles, but through the quiet, cumulative consequences of human choice.

Translated by Eva

Follow us on X, Facebook, or Pinterest