In the dim glow of an oil lamp on a winter evening in 1843, a 27-year-old woman paused over a stack of manuscript pages, dipped her pen, and wrote a sentence that would echo for centuries: “The Analytical Engine has no pretensions whatever to originate anything.” Augusta Ada King, Countess of Lovelace — known to history simply as Ada Lovelace — was annotating a dry technical article about a machine that did not yet exist. She was also, without quite knowing it, drawing a line between what a machine can be taught and what a mind can imagine on its own. A line we are still arguing about today.

Few stories better illustrate the strange dance between human foresight and technological readiness than Ada Lovelace’s brief, brilliant life.

A poet’s daughter disciplined against imagination

Ada was born in 1815, the only legitimate child of Lord Byron, the romantic poet whose passions scandalized Europe. Her mother, Annabella Milbanke, determined that no trace of poetic madness would take root in her daughter, and she subjected Ada to an unrelenting diet of mathematics and logic. Music was rationed; poetry largely forbidden. Yet the very rigor intended to suppress imagination seems instead to have sharpened it into something rare: a mind that could hold both the precision of equations and the sweep of possibility.

By her late teens, Ada moved in London’s scientific circles. In June 1833, at age seventeen, she attended a soirée where Charles Babbage demonstrated a portion of his Difference Engine — a gleaming assembly of brass wheels designed to compute mathematical tables without error. Most guests saw an elaborate calculator. Ada saw something larger. Babbage later recalled that she understood the machine’s principles better than many mathematicians present, and the two began a correspondence that would last until her death.

The silver lady and the difference engine

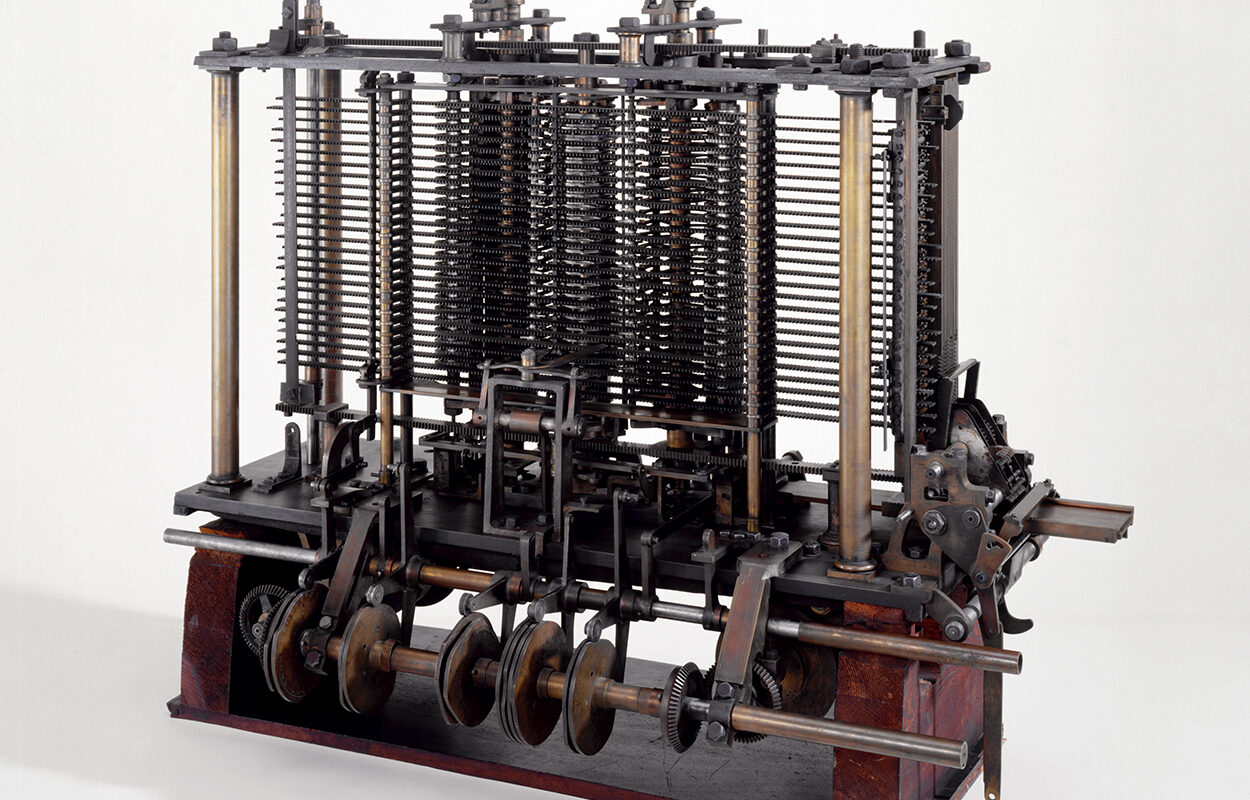

Babbage soon abandoned the Difference Engine for a far grander conception: the Analytical Engine, a programmable, general-purpose device using punched cards inspired by Jacquard looms. It featured a “mill” (what we would call the CPU) and a “store” (memory), capable in theory of any computation given enough time and cards. Funding evaporated; the machine was never built. Yet its design was sufficiently complete on paper to warrant genuine speculation about what such an engine might do.

In 1842, an Italian engineer named Luigi Menabrea published a description of the Analytical Engine in a Swiss journal. Babbage asked Ada Lovelace to translate it into English. She did more than translate. Over nine months, working while plagued by ill health and opium prescribed for pain, she tripled the length of the piece with a series of Notes labeled A through G. Note G contained what is universally recognized as the first complete computer program: an algorithm to compute Bernoulli numbers, complete with loops and conditional branching.

The first program and the first objection

The Bernoulli algorithm alone would secure Ada Lovelace’s place in history. But her true leap came in describing what the Analytical Engine might accomplish beyond mathematics. “It might act upon other things besides number,” she wrote. “Supposing, for instance, that the fundamental relations of pitched sounds in the science of harmony and of musical composition were susceptible of such expression and adaptations, the engine might compose elaborate and scientific pieces of music of any degree of complexity or extent.”

Then came the caution that still divides opinion: machines, she insisted, can only do “whatever we know how to order it to perform.” No originality, no initiative — only the faithful execution of human instruction. Some modern commentators dismiss this as a failure of vision. Others see it as a profound insight into the difference between syntax and semantics, manipulation and understanding.

Centuries of dreams deferred by matter

Ada Lovelace was hardly the first to see beyond the limits of her tools. In the 13th century, the Catalan mystic Ramon Llull constructed elaborate paper wheels intended to generate all possible knowledge through logical combination — an early dream of mechanical reason that lacked both symbolic logic and electricity.

In the same era, the Arab engineer al-Jazari built programmable humanoid automata that poured wine or played drums, marvels that remained curiosities because no power source existed to scale them. Leonardo da Vinci sketched ornithopters and armored vehicles that waited centuries for lightweight materials and internal combustion. In the 1670s, Leibniz imagined a “universal characteristic” in which all truths could be calculated, yet he died before Boole and Frege provided the mathematics he needed.

What unites these visionaries is not failure but prematurity. Their ideas were not wrong; the physical world was not ready. The gap between conception and realization can span decades or centuries, and during that interval, the vision is often mocked, forgotten, or misunderstood.

When yesterday’s impossibilities arrive unannounced

The 20th century compressed these gaps dramatically. Powered flight, dismissed as a fantasy by respectable physicists in the 1890s, became routine by 1910. Nuclear energy, speculated about by H. G. Wells in a 1914 novel, devastated Hiroshima thirty-one years later. The internet — first seriously described by J. C. R. Licklider in 1960 as a “galactic network” — felt like science fiction until the 1990s. Each arrival caught the previous generation by surprise, not because the ideas were hidden, but because the substrate — aluminum alloys, uranium enrichment, packet switching — had finally caught up.

We now live inside Ada Lovelace’s deferred dream. Every smartphone executes its style of stored-program control millions of times per second. Large language models generate sonnets and translate languages with a fluency that would have astonished her. Yet her cautionary note lingers. When a model produces an unexpected poem, we argue whether it has crossed the line she drew — or whether we have merely fed it subtler instructions.

Our own moving horizon

In November 2025, the frontier feels closer than ever. Claims of artificial general intelligence appear in corporate roadmaps; regulators scramble to define “sentience” in statutes. Meanwhile, researchers quietly point out persistent failures — models that collapse on simple reasoning tasks, hallucinations that no amount of scale eliminates, the stubborn absence of anything resembling grounded understanding.

History suggests humility. The Victorians who laughed at proposals for horseless carriages could not imagine interstate highways. The 1950s engineers who filled entire rooms with 5 kilobytes of memory could not foresee devices slipping into pockets with billions of times that capacity. We stand in the same relation to the future as Ada Lovelace did to ours: able to glimpse shapes through fog, but unable to touch them.

What remains constant is the human element. Machines amplify intention — benevolent, frivolous, or destructive — yet the spark of purpose originates elsewhere. Ada Lovelace, daughter of a poet, knew this intuitively. Her incredible insight was not only that the Analytical Engine could weave algebraic patterns like a loom weaves flowers, but that the flowers themselves, the decision to weave beauty rather than mere utility, would always begin in a human mind.

She died in 1852 at thirty-six, in pain and largely forgotten by the scientific establishment. A century later, her notes were rediscovered and recognized as foundational. Today, her portrait hangs in Downing Street, a quiet reminder that the summit we think we have reached is often only a ridge concealing higher peaks.

The story of technological progress is less a march toward completion than a relay of partial visions, each generation handing the baton further than it could itself run. Ada Lovelace handed us a torch whose flame we are only now learning to shield from the wind. Whether the next hand to receive it will see farther — or merely believe the light has reached its final strength — remains, as always, a question not of brass wheels or silicon chips, but of the imaginative courage to doubt our own certainties.

Follow us on X, Facebook, or Pinterest