One of the most acclaimed Hong Kong writers, Ni Kuang, was born in Shanghai into an intellectual family from the eastern coastal province of Zhejiang, China. In 1951, 16-year-old Ni Kuang was deeply moved by communist propaganda and became determined to pursue the ideal of creating heaven on earth as envisioned by the Communist Party. He received three months of training and was given the title of “public security officer.”

Embracing communism

From 1952 to 1953, he participated in the land reform movement in southern Jiangsu Province that persecuted landowners and arrested “anti-revolutionaries.” When a landlord was sentenced to death, his superior assigned Ni Kuang to write an announcement. Ni Kuang asked the reason for the death sentence. His superior replied: “He is a landlord.” Ni Kuang then said: “Being a landlord does not constitute a death sentence.” His superior responded impatiently: “I asked you to write an announcement, not to give your opinion.”

In 1955, Ni Kuang volunteered to become a prison guard in a newly opened labor camp in Inner Mongolia and was responsible for managing the prisoners on the work farm within the labor camp. During that time, one of Ni’s guard dogs bit the Party secretary of the inspection team, so he became the target of repeated condemnation. Ni Kuang was forced to reflect on his “mistakes” and admit that he had “potential counter-revolutionary thinking.”

Ni Kuang shared his experience in the winter of 1956 when coal trucks failed to deliver coal due to a snowstorm, resulting in many people freezing to death. He dismantled a crumbling wooden bridge for firewood and thought that he was saving his comrades’ lives, but he was accused of a serious crime — “vandalism of public property.” Ni Kuang was locked up in a small abandoned house with a broken door and no heat. Every night, the house was surrounded by wolves howling, which horrified him. When he learned that he would be sentenced to 10 years in prison, he could no longer bear it. At the end of 1956, he escaped at night and planned to flee to outer Mongolia by horse.

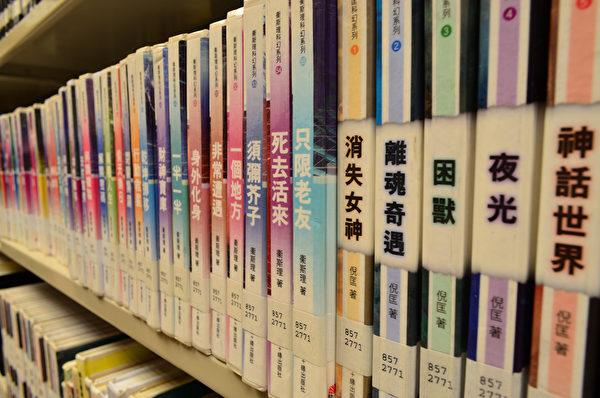

With no coal available for fuel during the winter of 1956, he dismantled a crumbling wooden bridge for firewood to save his comrades’ lives and became a criminal for ‘vandalism of public property.’ (Image: via The Epoch Times)

But by mistake, he arrived at the train station and took a train headed south, to Dalian City, and then headed to Shanghai by boat. His family in Shanghai was afraid of sheltering him, a fugitive on the run, so he looked for an opportunity to be smuggled into Hong Kong, a British colony at the time. Later, he and a dozen other people were stuffed, along with a shipment of vegetables, into the bottom of a ship bound for Hong Kong. The bottom of the ship was extremely crowded and the smuggled people could only rest and stretch on the upper deck when there were no ships patrolling the international waters.

On a rainy day in July 1957, Ni Kuang paid US$20 to land in Hong Kong. Upon arrival, he was taken to a government agency to apply for an identification card and became a Hong Kong citizen under British jurisdiction. That year, he was 22 years old.

Years later, Ni Kuang expressed: “If I had not come to Hong Kong from the mainland, I would have neither the opportunity to write nor to even survive. I am sure that I would not have lived through the ‘anti-right’ movement or the ‘Cultural Revolution.’ It was my luck to come to Hong Kong…”

Ni Kuang became Hong Kong’s highest-paid writer

When Ni Kuang first arrived in Hong Kong, he had no higher education and did not speak Cantonese. All he could find were odd jobs and physical labor, but he was very content with his life simply because he had the freedom to live and was able to enjoy a meal of roast pork and rice. After three months of hard labor, Ni Kuang decided to become a writer and published his first novel, Buried Alive, in October 1957. This novel was written in one afternoon and brought in about US$12.75 of royalties, which was more than his one-month wage as a laborer. His novel received rave reviews, and after that time, Ni Kuang put his focus on writing. Throughout his career as a writer, his work has never been rejected. He became the highest-paid writer in Hong Kong.

Patriotism is anti-communism, anti-communism is patriotism

Fifty years after Ni Kuang left mainland China, Asia Weekly offered him a trip to visit his hometown in the mainland. He declined, but one of his good friends accepted the trip, which made Ni Kuang very upset and he criticized his friend: “He has none of the integrity or backbone of an intellect…”

Ni Kuang’s anti-communist stand is very firm. He strongly believes that the actions of the CCP (Chinese Communist Party) have completely violated humanity. “The most frightening element of the Communist Party is brainwashing and controlling individuals’ thoughts. People in the Communist Party system will only become completely obedient machines.”

Ni Kuang also declared that he is a patriot of China — “love to the extreme!” He wrote two slogans: “Patriotism is anti-communism; anti-communism is patriotism.”

Ni Kuang said that he fled to Hong Kong to escape communism, but he admires the courage of Hong Kong’s young people today: “I escaped, but today’s young people did not escape; instead they chose to stay and fight; and for that I admire them… The greater the pressure, the stronger the resistance.” He affirmed that he will always support the young people. “My personal stance — no matter what happens, I stand with the young people.”

Translated by Yi Ming and edited by Angela

See Part 2 — Ni Kuang: The Revelation of Hong Kong

Follow us on Twitter, Facebook, or Pinterest