Ethical strength often appears in everyday moments — when ordinary people must choose between comfort and principle, anger and restraint, or personal loss and public good. The following accounts, preserved in historical records from the Jin and Ming dynasties, highlight how individuals responded when confronted with injustice or provocation. Their choices show how righteousness, gratitude, and self-discipline can shape not only one life, but a community.

The woman who sought justice over money

A record from Continued Records of Yi Jian describes the case of a laborer named Dai Shi, who settled in a small village southeast of Luoyang after the fall of the Jin Dynasty. Little was known about his background, and he supported his wife, Liang, and their two young children by taking on manual work and tending a small bean field.

In August 1243, a military translator allowed his horse to graze in Dai’s field. For a family that lived from harvest to harvest, those few rows of beans were essential. When Dai drove the horse out, the translator — once a servant in a powerful household and now emboldened by his position — flew into a rage. He beat Dai with a horsewhip so violently that Dai died on the spot.

Liang lifted her husband’s body and carried it to the nearby military camp to report the crime. Fearing the consequences, the translator went to Liang’s home with two oxen and 50 taels of silver — an enormous sum for a widow with small children. He urged her to accept compensation, arguing that killing him would not bring her husband back and that the money would keep her family alive.

Liang refused. “My husband was innocent, yet he was beaten to death,” she said. “This is a matter of justice. If someone with wealth can buy his life after killing a good person, he will harm others again. That would only endanger the people.”

Those present saw that she would not compromise. Someone asked whether she intended to kill the man herself. Liang replied that she did not fear doing so and reached for a knife. Worried that she would make him suffer in her grief and anger, the onlookers intervened and executed the translator in her stead. Afterward, Liang gathered her children and quietly left, choosing hardship over allowing violence to be excused by wealth. Her stance left a lasting impression on all who witnessed it.

The inspector’s gratitude

A similar lesson in moral transformation appears in Yongchuang Xiaopin, a collection of anecdotes from the Ming Dynasty. In the Xinchang region, Inspector Lü Guangxun’s father had once been a powerful bully whose behavior made him feared locally. When Cao Xiang, a magistrate from Taicang, took office there, he investigated the man’s abuses, arrested him, and ordered a lawful beating. The humiliation broke years of arrogance, and Lü’s father gradually began to reform himself.

Years later, Lü became an imperial inspector and happened to pass through Taicang during his official travels. He sought out Cao Xiang to express his gratitude. Cao, now older, no longer remembered the incident, but Lü recounted how that single punishment had changed his father’s life. “Without your actions,” he said, “my father could not have corrected himself. He remembered your virtue for more than ten years.”

Lü stayed through the evening, speaking with the magistrate before eventually returning to his duties. Before leaving, he presented Cao with a large sum of money — not as repayment, but as acknowledgement of the act that had redirected his family’s course.

An official endures insults

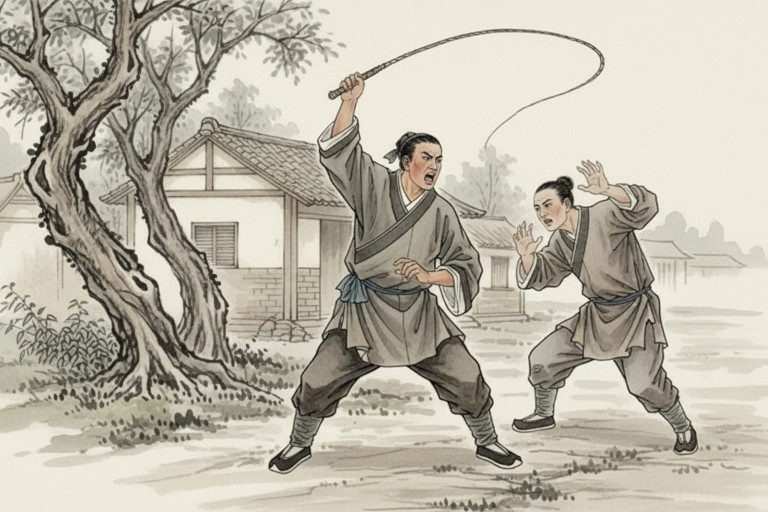

Another account from Yongchuang Xiaopin recounts the conduct of Cao Shizhong, a deputy envoy of Zhejiang and a native of Huating. Among his neighbors was a young man with a harsh temperament who held on to old grievances. Seeking to shame Cao Shizhong, he wrote the official’s name in white powder across the rear of a cow and drove it through the streets. He also whipped Cao’s servant while shouting insults, hoping to provoke a reaction.

When the servant returned home and reported what had happened, Cao did not react with anger. Instead, he told the servant: “If someone insults me and you repeat his words, you only spread the insult further. Do not pass it on. Go and apologize to him and put an end to this quarrel.”

Not satisfied, the young man sent a letter that looked respectful on the outside, but was filled with insults. His servant delivered it while kneeling, yet Cao did not open it. When his own servant returned, he simply had the letter burned unread. Then he said to the messenger: “I already know your master has no kind words for me, yet I still wish him well.”

Hearing this, the young man felt deep shame and stopped harassing the official. Cao Shizhong lived to the age of 90, remembered for a calm strength that allowed him to meet insult with composure rather than retaliation.

Translated by Joseph Wu

Follow us on X, Facebook, or Pinterest