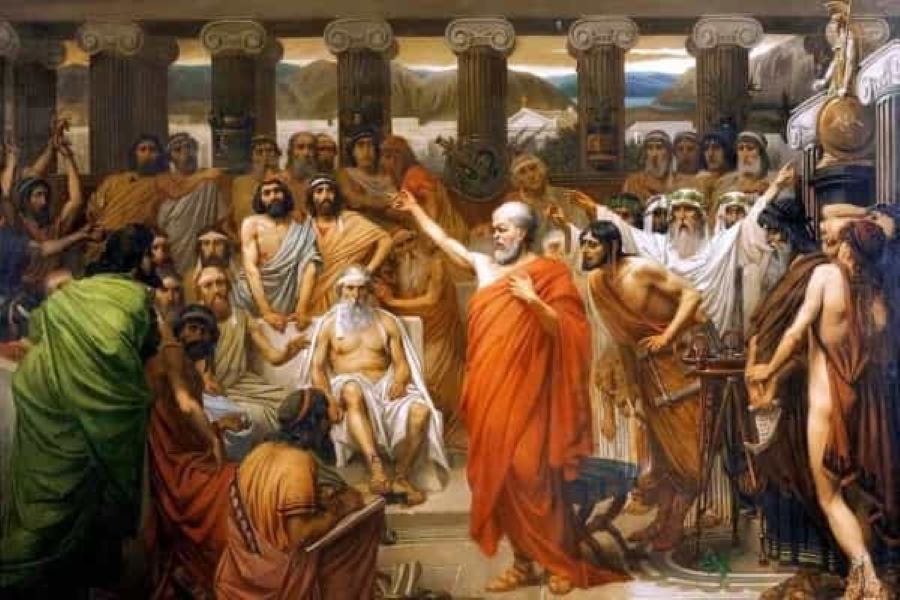

More than 2,000 years ago, history witnessed a remarkable convergence, as if humanity’s greatest sages had silently arranged to appear in the world at the same time. In China, there was Laozi; in ancient India, Shakyamuni (the Buddha); in the West, Jesus; and in ancient Greece, Socrates. Their arrival laid the spiritual and moral foundations of human civilization across the world’s regions.

Among these four, Socrates stands apart. Though revered as a sage, he remained firmly grounded in the human realm. He performed no divine miracles, achieved no supernatural feats, yet his courage, justice, self-restraint, and kindness radiated a rational light that transcended the ordinary. The philosophy he articulated, along with his calm acceptance of life and death, mirrors the spiritual cultivation practiced by ancient Chinese seekers of the Dao.

Above all, his famous declaration — “The unexamined life is not worth living” — still resonates like a thunderclap, awakening minds even today.

A noble character

Socrates was born in Athens in 470 BCE. His father was a stonemason, his mother a midwife. The family was not wealthy. From an early age, Socrates received the standard education of the Athenian city-state. He loved learning, delighted in thinking, and often stopped people on the streets to engage them in conversation.

He seemed to know something about everything — friendship, love, marriage, art, poetry, religion, science, war, politics, justice, goodness, courage. There was hardly a topic he would not explore. Yet beneath all these discussions lay his deepest concern: moral cultivation. He urged people — young and old alike — not to worry first about their bodies or possessions, but to care above all for the greatest improvement: that of the soul. This was the very heart of Socratic philosophy.

Socrates had no attachment to material desires. He believed that “the closer one is to the divine, the fewer needs one has.” He ate plain food with little seasoning, walked barefoot, and wore the same old cloak year after year. His standard of living was extremely modest — though, given his fame, he could easily have lived comfortably.

The nobleman Alcibiades once offered Socrates a large piece of land on which to build a house. Socrates declined as he smiled and said, “If I needed a pair of boots and you offered me an entire animal hide to make them from — and expected me to accept it — wouldn’t that be absurd?”

With this simple metaphor, Socrates made his principle clear: he required very little to live and valued only what was truly necessary. Excess wealth or possessions held no appeal for him.

Wisdom, humor, and unshakable calm

Socrates was generous in spirit and boundless in energy. Nearly every day, he sought people to converse with. He liked to ask deceptively simple questions: What is goodness? What is beauty? What is courage?

Yet under his questioning, most people quickly realized they did not truly understand the words they used so confidently. As their ignorance was exposed, many felt humiliated. Resentment grew. Some debates turned into mockery and abuse; others even escalated into physical attacks. Socrates endured it all — never striking back, never returning insults.

Once, after being beaten, someone asked him why he tolerated such treatment. Socrates replied calmly: “If a donkey kicked me, should I follow the donkey’s example and kick back?” At home, his patience was even more remarkable. His wife Xanthippe was famously sharp-tempered. She often scolded Socrates for being idle, claiming he brought more bad reputation than bread into the household.

One day, while Socrates was teaching, Xanthippe stormed in and unleashed a torrent of insults. Socrates simply listened, unmoved. When she finally left, he resumed his lesson. Moments later, a basin of cold water came flying down, soaking him completely. Drenched and disheveled, Socrates merely chuckled: “I knew that after thunder, rain must surely follow.”

He regarded life with Xanthippe as a form of spiritual training. “I live with Xanthippe,” he once said, “as a horse trainer loves a spirited horse. After taming a fierce horse, he can handle any other with ease. Living with her teaches me to adjust myself and adapt to anyone.”

Thus arose the Western saying: “A fierce wife can make a philosopher.” Socrates’ endurance was not weakness, nor clenched-teeth suppression — it was calm, effortless, as though the blows and insults belonged to someone else entirely.

Strength of body and spirit

Socrates possessed not only inner strength but also a powerful physique. During the prolonged war between the Athenian and Spartan alliances — a conflict that lasted nearly 30 years — his conduct on the battlefield was exceptional.

In the first campaign, at age 40, Socrates saved the life of his student Alcibiades, then only 20 years old but already a commanding officer. Alcibiades later praised Socrates sincerely, noting that no soldier endured hardship better than he did. When food ran out, no one tolerated hunger like Socrates. In brutal winters, while other soldiers wrapped their boots in felt to guard against the cold, he walked barefoot across ice in his thin old cloak — yet appeared more comfortable than those fully equipped. Alcibiades even asked that Socrates be awarded a medal for bravery, but he refused.

During the disastrous retreat after Athens’ defeat at the Battle of Delium, Socrates walked calmly, head held high, glancing serenely to either side. His composure so unsettled the enemy that they avoided him entirely, choosing instead to pursue the fleeing soldiers.

His courage earned the admiration of fellow soldiers and even General Laches. His wisdom and virtue captivated Athenian youth, many of whom followed him for years, listening to his debates and seeking his guidance. Socrates taught without charge, never collecting tuition. He carried no airs of authority; in fact, his students felt more like friends or brothers than disciples.

(To be continued)

Translated by Katy Liu and edited by Tatiana Denning

Follow us on X, Facebook, or Pinterest