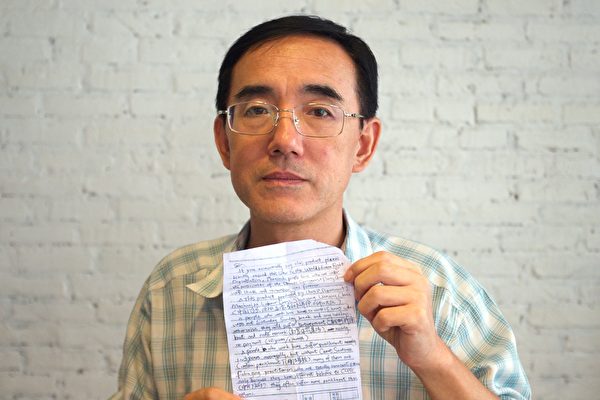

In October 2012, a handwritten note of distress was written by a slave labor prisoner in one of China’s forced labor camps. It was hidden in a Halloween decoration set produced in the prison. The decoration set was then shipped to the state of Oregon where it was purchased by Ms. Julie Keith. When she discovered the note inside the box, she went to the media and shared its contents with the world.

The note was written by a Falun Gong practitioner named Sun Yi. He risked his life in order to write as many as 20 such letters, and hid them in boxes of decorations. One of these letters finally landed in Julie Keith’s hands. Only then were the dark secrets of China’s forced labor camps exposed.

Unfortunately, even though Sun Yi would eventually escape from China by fleeing to Indonesia, he suffered from an illness and shortly afterward died in an Indonesian hospital. His body was burned under suspicious circumstances.

The notorious nature of China’s prisons, detention centers, and labor camps arises from the totalitarian system that is the cause of China’s slave labor. This slave labor is used in producing goods that are then exported.

The notorious nature of China’s prisons, detention centers, and labor camps arises from the totalitarian system that is the cause of China’s slave labor. (Image: via Pixabay)

Let’s examine China’s slave labor system

1. Trade agreements and laws

Despite existing trade agreements and laws that prohibit the exporting of prison-derived products, it has been found that more than 100 different types of products — ranging from food, apparel, household products, and cosmetics — are produced by forced labor in China’s prisons. These products have been sold to the United States, Australia, Asia, Russia, and Europe.

2. Prisons and labor camps in China

Based on preliminary statistics, there are nearly 100 prisons, forced labor camps, and detention centers in China that use slave labor to produce goods. Most are located in the cities of Anhui, Beijing, Gansu, Guangdong, Henan, Heilongjiang, Shandong, Shanghai, and Tianjin.

3. No regulations or standards

International regulations require that food and clothing must be protected from infectious diseases while being produced. But in China’s prisons, there are no regulators to perform hygiene inspection on food products, nor to provide qualification certificates for apparel.

In China’s prisons, there are no regulators to perform hygiene inspection on food products, nor to provide qualification certificates for apparel. (Image: via Pixabay)

For example, there was a case in Yunnan Women’s Labor Camp where a Falun Gong practitioner refused to make biscuits. The prison guard demanded to know why. She replied: “Would you buy these biscuits? Bags of flour are stacked on the muddy floor and the machines for making the biscuits are full of dust. Do you think these biscuits meet hygiene standards? Our toilets are full of stinking urine, and it is all over the floor, without a clean space to place our feet. We don’t even have towels to wipe our hands after we defecate, and we can only wipe them on our aprons that we then use to clean our hands that wrap the biscuits. Do you want to eat one of these biscuits? I am practicing Falun Gong, which centers on truthfulness and compassion, so I cannot create food that will harm others.”

Another example occurred in the First Women’s Prison in Inner Mongolia. Most inmates were weak, sick, and detained in cell blocks. They were not fit to work in production lines due to liver disease, tuberculosis, and old age. As a result, they were forced to do other jobs, such as picking unwanted threads from sweaters. In order to complete their task within the specified time, they used a filthy shoe brush and then folded the garment with their dirty hands. These goods were then exported to countries across the world.

4. Toxic work

China’s prisons are the ideal place for work that commercial enterprises cannot undertake in the open due to regulations and safety standards.

For example, the Jiamusi Forced Labor Camp in Heilongjiang Province forced inmates to handle toxic rubber and raw materials that are used to produce gloves and car seat cushions. The camp is filled with pungent and poisonous discharges in the air that even the prison guards cannot tolerate. An air assessment conducted by the internal technical team found that the risk level for carcinogens from the raw materials far exceeded safety standards. After that, the prison guards chose to stay outdoors even during the cold winter and did not want to enter the workplace. However, the inmates were forced to complete a high production quota daily and many suffered from nosebleeds, heart palpitations, breathing difficulties, red swollen eyes, and severe bodily damage.

5. Inhumane hours

Slave laborers are forced to work for 10 to 20 hours a day. When the production quota is high, the laborers are not allowed to close their eyes to rest, and this continues for several days and nights. Based on estimates, 36.11 percent of slave laborers are forced to work for 12 to 14 hours a day, 25 percent for 16 to 18 hours, and 19.44 percent for 14 to 16 hours.

6. Wages

Most slave laborers in detention centers are not paid for their work. The lucky few receive a couple pennies worth of Chinese currency a month. The only firm example of an actual wage is in Shandong’s First Women’s Labor Camp, where slave laborers receive the U.S. equivalent of 75 cents to $14.70 a month because of a contract that is required to be followed in order to produce such exports.

7. Apparel production increasing

Having already established food and machinery labor, China’s prisons are now focusing on apparel production. The World Bank wrote a report titled “Stitches to Riches,” released in 2016, that stated China is the world’s largest apparel manufacturer and accounts for 41 percent of global production. According to industry sources, China’s prisons account for about 10 percent of its national production.

The Investigation Report on the Production of Slave Labor Products by Falun Gong Practitioners in China states the first, fourth, fifth, and seventh prisons and forced labor camps in Zhejiang Province have long-term agreements with Zhangzhou Haolong Garments Co., Ltd. This company has more than 20,000 workers that include illegally detained Falun Gong practitioners. So the prisons are using slave labor to produce clothes that are then sold throughout China and the world.

Translated by Chua BC, edited by Derek Padula

Follow us on Twitter, Facebook, or Pinterest