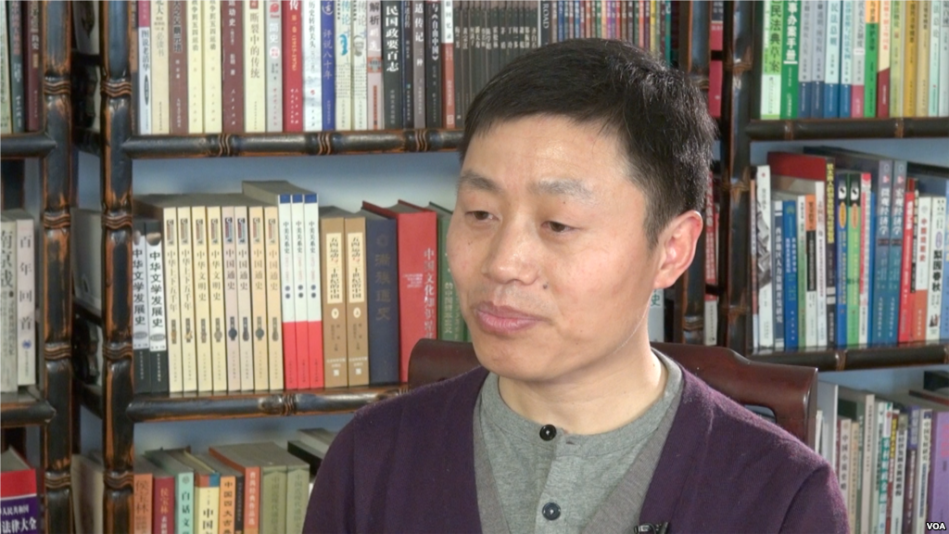

From starting out as an official media photojournalist before 1999 through becoming an independent journalist, writer, and documentary producer today who pays attention to rights activists and exposes the truth of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), Du Bin has been named by the CCP as “an expert in muck spreading.” Due to that unofficial title smearing his reputation, he consequently lost his job with The New York Times and was once illegally detained. Du Bin was pragmatic when he said:

“I feel it is worthwhile for me to do that.”

Du Bin accepted an interview with The Epoch Times on the occasion of the publication of his new book Changchun Hunger Siege. In this interview, he talks about his experiences and writing process for the book.

Du Bin accepted an interview with The Epoch Times on the occasion of the publication of his new book, ‘Changchun Hunger Siege.’ (Image: via The Epoch Times)

Reporter: What made you decide to write the book Changchun Hunger Siege? How did you find the materials and were they hard to come by?

Du Bin: The Siege of Changchun has always been a very sensitive topic. It is very different from the Nanjing Massacre because during the siege, hundreds of thousands of Chinese people starved to death, so I still faced some risks in researching and writing this book. In fact, I wanted to figure out one thing: Why did you have to starve hundreds of thousands of people in order to seize political power? I wanted to know how they starved to death. How many actually died? Whose responsibility was it? Who should bear the guilt of this page of history?

Du Bin spent 10 years doing research for his book ‘Changchun Hunger Siege.’ (Image: via The Epoch Times)

I felt that I was willing to take some risks when writing this book in order to let me stop thinking about what happened. Since I knew what happened in Changchun, if I didn’t write about it, I couldn’t talk about it, and then I would think about it every day. I was worried and couldn’t even sleep at night. It’s as if I saw my friend go missing, being arrested, and being sentenced. I kept silent, didn’t do anything for him, didn’t write an article for him. I didn’t shout for him. If that happened, I would feel embarrassed about my inaction. I have a camera and can write. I would feel ashamed if I didn’t do anything. I can do something, and I will do something.

Author Du Bin: ‘I have a camera and can write. I would feel ashamed if I didn’t do anything. I can do something, and I will do something.’ (Image: via The Epoch Times)

Du Bin spent 10 years writing a book about Changchun

The information was hard to find. I spent nearly 10 years researching and writing this book and collecting information. On some websites selling old books, I searched every night for keywords such as “1948 Changchun” and “Changchun Besieged Northeast Field Army Lin Biao.” Once I found a related book, I would buy it immediately.

I finished the writing about Changchun and tried my best to figure it out so then I could forget about Changchun. Only after forgetting, could I move on and do other things. Now that I have finished it, I feel that I have done my best. For the time being, I can put it aside.

If there is a piece of evidence, I will say something. Without this evidence, I will say nothing.

Reporter: In Changchun Hunger Siege, you use the method of compiling daily activities to describe the historical materials. Why is that?

Du Bin: In the process of writing the book, I experienced pain on the inside, for I could not write freely. If I had done that, I would have added my own emotions to the process. After repeated struggles, I finally decided that I would say a few words for each piece of evidence. Where there was no evidence, I would say nothing. I wanted to make sure that every paragraph in the book had its source, and every quote had its source.

In the end, I decided to use a diary to showcase the story: What was the CCP’s army doing on a certain day? What was Chiang Kai-shek’s army doing? What were the people living in Changchun doing? What were the people living outside Changchun doing? Also, what was Chiang Kai-shek doing? What was Mao Zedong doing? What were the senior commanders doing? I just wanted people to look at these details this way.

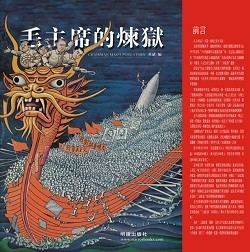

I have written a few other books in the same style, such as Chairman Mao’s Purgatory; Mao Zedong’s Regime of Human Flesh; and Tiananmen Square Massacre. The reason for doing this is to restore history by presenting the collected information using the original text. If I used my information and wrote freely, it would become another style. The book might have gained more readers. People might have preferred it that way. But I think that in order to present history in its original form, using the diary style is the better way.

Du Bin’s 2011 book ‘Chairman Mao’s Purgatory’ was written in the same diary style for the purpose of restoring history by presenting the collected information using the original text. (Image: via The Epoch Times)

In fact, some of the materials I used in the book, or it should be said that two-thirds of the contents are from official publications as well as internal information. Internal information is not a state secret, which means that it was disposed of as a second-hand book and was collected by me.

Reporter: In the process of reading the information, what touched you the most?

Du Bin: In 1948, in the newspaper Tianjin Yi Shi Bao that was established by Catholic missionaries in China, there was an article about tens of thousands of refugees from the Northeast. They had nothing to eat or drink and slept on the ground in the open air. Next to the article was a letter from Tianjin reader Anton Dong. The letter reads: “We are both human beings coming from the same ancestors. All of us should express sympathy. Although I am not a refugee, the refugees are my compatriots. I am not rich but still have enough to eat.”

He sent all his hard-earned money to the newspaper and hoped that the editor could forward the money to the refugees in the Northeast.

In fact, this article is the size of a block of tofu, you can only see the title, and I had to zoom in on the computer to read the content. Despite the small space given to the text, these words saddened me. Did the Communist Party see that ordinary people have this kind of consciousness? Anton Dong would never have thought that the letter he wrote, after 68 years, could still touch another person’s soul. I felt like crying a little.

Reporter: When you talk about writing this book in Changchun, it was very difficult for you to find a surviving witness. Why was it difficult? What was the reason behind that?

Du bin: Yes, it was very difficult. When I was wandering around Changchun, I was so desperate I would even have tried to ask a passing-by dog: “Do you know what happened to Changchun in 1948? Do you know where those survivors are now?”

For example, I wanted to interview a surviving elderly man. After the initial contact, I made an appointment, but then he said that he would report it to the CCP unit who is in charge of him. I was terrified when I heard it. He is 79 years old, but when he met with a reporter, he had to report it to the officials. I was scared and it looked like this would be troublesome. What if they asked about my identity? I had no work unit. Later, he reported to his work unit. He belonged to the veteran warriors. He often talked to students and soldiers about these things. He has talked about his family a few hundred times. Of course, he believed that the Kuomintang was responsible for the Changchun incident. He was grateful for the Communist Party and believed that the Communist Party saved him.

My conclusion is that hundreds of thousands of people died. The Changchun incident is not a trivial matter. The authorities do not see us as human beings and treat us like animals. I think we, Chinese people, have not lived like human beings from 1949 to the present day.

I think that on many overseas social media, such as Twitter, Facebook, and other platforms, foreigners are talking about fun things and happy events, but the Chinese people are basically sad: Someone was arrested for something, someone was sentenced for something, and these are human rights violations. Human rights cannot be spoken about in China, but they can be said aboard. I browse the news outside China every day and feel very sad.

Reporter: Have you given your books to your father? I heard he is an old party member of the CCP.

Du Bin: Yes, he is a member of the Communist Party and Secretary of the town Party Committee. After he read Chairman Mao’s Purgatory, he told me: “After reading your book, I can’t go out and talk about it.” The Director of the Safety Bureau came to visit my father. He said: “Tell your son not to write books that the government is afraid of.” My father said: “Oh, this child is old enough. Sometimes he’ll listen to me, but sometimes he won’t.” Actually, my father was very scared of the things I do. He was also afraid of the job I had with The New York Times. Because of my age, my father urged me to get married, have a family, and have children.

Later, my father was seriously ill, and I feel quite guilty that I could not go back to see him before he died. Because I was on bail pending trial at that time, I had to report to the police if I left Beijing. They kept my ID card. I don’t think I could have bought a ticket without my ID card… but I did not waste any time. I gave all my energy and enthusiasm to what I had to do. The thing I did was to write about what should be left behind and what is worth keeping. Therefore, the book Changchun Hunger Siege is dedicated to the hundreds of thousands of people who were starved to death, and it is also dedicated to my father.

I gave all my energy and enthusiasm to what I had to do. The thing I did was to write about what should be left behind and what is worth keeping. (Image: via The Epoch Times)

My illiterate, aging mother is over 70 years old and still working every day. I bought a mobile phone and asked her to call me. She was afraid of spending money. She didn’t use the phone. When it got dark outside, she went to bed. She said: “Don’t waste money.” She even told me not to go home during the New Year, just to save money.

Reporter: Why do you like being a reporter?

Du Bin: At first, I wrote poems, but I thought that I should not write literary things. I should be a journalist.

Here is how I became a journalist. Once I heard from a friend that there was a poor family in the countryside. The father of the family built houses for other people. Unfortunately, he fell, broke his spine, and became bedridden. His wife planted the field with four other members of the household, namely, a grandmother, two girls, and a boy. I went to their house and told them: “I don’t have the money to help you. I want to do a feature story with pictures and see if that could help you. I won’t drink your water, or eat your food. I will bring bottled water and come to visit only once.”

I sent my story to several newspapers. Later, I heard that this family had received more than US$3,000 in donations.

In 1999, that was a lot of money. I never imagined that staying with them for a day and writing an article could really help them. I was especially proud, happy, and thought it was good to be a reporter. Since then, I have vowed to be a journalist to help more people.

But I have always been more concerned about the little guys.

During the 2008 Beijing Olympics, The New York Times gave me a certificate and asked me to go to the Olympic Stadium. I was terrified because I was a layman in sports, and in the end, they decided not to let me go.

At that time, the atmosphere was particularly tense, and people were wearing red armbands on every street. During the Olympics, I took a lot of photos, for example, migrant workers who were forced to leave Beijing at the railway station. The Olympics will be held tomorrow. So today, they rush the migrant workers out of Beijing, and they will go back home because the city of Beijing does not want them.

During the Olympics, I was more concerned about Yang Jia. His family was very close to the Olympic Games. There was a carnival there, and Yang Jia was locked up inside, while his mother was missing.

On May 1, 2010, the World Expo opened in Shanghai, and I published my book Shanghai Cavalry on April 27. A lot of places received a notice to check this book, such as the industrial and commercial departments of Jinan, Jiangxi, Xinjiang, etc. They were ordered by the notice to inspect for illegal publications, including my Shanghai Cavalry. I also found the notice from the courier company online.

Reporter: You work for The New York Times in the United States. If the photos taken are not welcomed by the Chinese government, will there be problems?

Du Bin: Well, in 2008, Falun Gong practitioner Yu Zhou died in a detention center in Beijing. This news was found online. At that time, Yu Zhou’s wife had been sentenced. From the Internet, we found Yu’s sister. After the contact, I took a five-inch photo of Yu Zhou and sent it to The New York Times.

Later, I heard that the Ministry of Foreign Affairs reprimanded the journalist and told him not to mention bad things about China, for example, the fact that one could not ask for a lawyer, and that more than 3,000 Falun Gong practitioners had died from persecution.

As long as you know China well, you are clear about the things that the Communist Party has done for decades. Sorry, you are not allowed to come in. If you do negative reporting, which is not good for the Communist Party, they will stop you.

After the establishment of diplomatic relations between China and the United States in 1976, some journalists were stationed in China. However, monitoring was very tight as long as you were in contact with the Chinese, for example, you called the Chinese about an interview. Before you even went, the official sent someone to block you from seeing that person. So, you could not see anyone.

In 2012, there was a reporter from a television station, a Chinese-American female journalist. She did a video report on labor camps, and the response was very strong. The government was not happy. In the end, the reporter was forced to leave China. Later, the English channel of that station in Beijing was closed.

I have contacted a few foreign media reporters. When I see someone or write a story, I will first examine my potential actions: Will seeing this person or writing this article make the Chinese government unhappy? Or will it be troublesome to get a visa in the future? Foreign journalists want to write good news in China to make contributions, so they are working carefully and not stepping on the CCP’s toes.

Follow us on Twitter, Facebook, or Pinterest