On April 28, 1904, a 15-year-old girl stood on the Huangpu River dock in Shanghai, ready to leave for the United States. Her name was Soong Ai-ling. Her father, Soong Yaoru, entrusted her to the care of Pastor William Burke, a close friend and former classmate from Vanderbilt University, who would accompany her to the U.S.

Thanks to Pastor Burke’s strong recommendation, Soong Ai-ling was accepted into Wesleyan College in Macon, Georgia — the first government-recognized women’s college in the United States. Affiliated with the Methodist Church, the college was known for educating daughters of elite families.

Barred from entering the U.S.

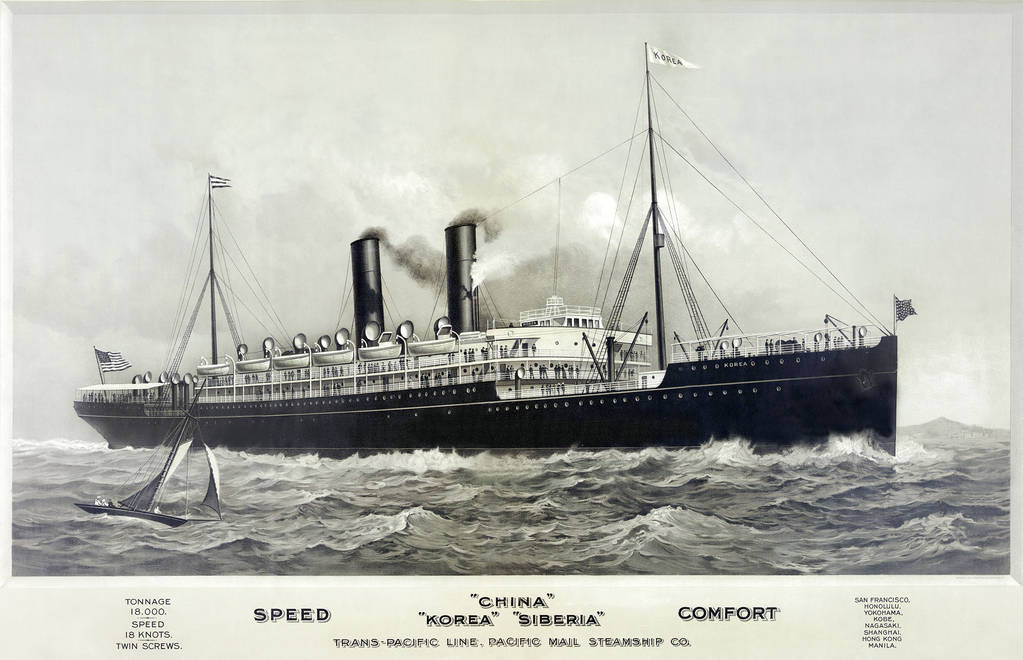

The journey, however, was far from smooth. After more than two months at sea, the steamship Korea finally arrived in San Francisco on July 1, 1904. But when Soong Ai-ling attempted to disembark, immigration officials refused her entry, claiming her documents were incomplete. One officer even proposed sending her to a detention center, only to be overruled by another who said the place was “not fit even for animals.”

Deeply humiliated, the young Soong returned to the ship, furious but silent. Over the next three weeks, she was shuttled between four nearly empty vessels, confined and isolated while her fate remained uncertain. Her case eventually caught the attention of a missionary in San Francisco, who appealed to government officials in Washington, D.C. Only then was she finally allowed to enter the country and begin her studies at Wesleyan College.

Confronting President Roosevelt at the White House

In December 1905, Wen Bingzhong — a trusted advisor to Empress Dowager Cixi and Soong Ai-ling’s uncle — led an educational delegation to the U.S. The following January, he brought Soong Ai-ling from Macon to Washington, D.C., to attend a banquet hosted by President Theodore Roosevelt.

During the event, Roosevelt asked the young student what she thought of America. Soong Ai-ling replied with a smile: “The United States is a beautiful country, and I’m happy to be here. But why do you call it a free country?” She recounted her traumatic experience at the San Francisco port, adding: “If America is truly free, why was a Chinese girl turned away? In China, we would never treat our guests that way.”

The president, visibly taken aback, offered a murmured apology and moved on. The next day, a local newspaper reported on the incident under the headline “Chinese Girl Protests U.S. Anti-Chinese Policy.”

A small-town farewell and a national prediction

By the time she graduated in 1909, Soong Ai-ling — now known as Alice — had left a deep impression on the town of Macon. At the graduation party, she captivated the crowd by reciting a passage from Madame Butterfly in her sweet, clear voice.

Before her return to China, the Macon Telegraph published a half-page tribute predicting: “Miss Soong will become the wife of the Chinese leader.” That bold forecast would soon come true.

In the spring of 1914, Soong Ai-ling married Kung Hsiang-hsi (H. H. Kung), who went on to serve as Premier of the Executive Yuan in China.

Her sisters followed, with smoother paths and greater fame

In the summer of 1907, Soong Ai-ling’s uncle Wen Bingzhong returned to the U.S., this time bringing her younger sisters, Soong Ching-ling and Soong Mei-ling, to study at Wesleyan College as well. Unlike their older sister, they passed through immigration without issue — thanks to Wen’s diplomatic status and the company of well-known American educator William Grant.

Soong Ai-ling had been the first of the three sisters to meet an American president. Later, her younger siblings would each become legends in their own right: Soong Ching-ling, honored as the “Mother of the Nation,” and Soong Mei-ling, who became China’s First Lady.

Translated by Chua BC, edited by Maria

Follow us on X, Facebook, or Pinterest