In the crowded theater of global conspiracies, no cast looms larger than the Illuminati. From whisper networks of 18th-century salons to the fever-dream digital musings of Instagram prophets, the narrative of a secret world order persists — shifting in tone, language, and scope but rarely in core assertion: that a cabal of elite decision-makers directs humanity from behind the veil. But what if the story, at its roots, is both more mundane and more fascinating than the fiction suggests?

The Enlightenment roots of the Illuminati

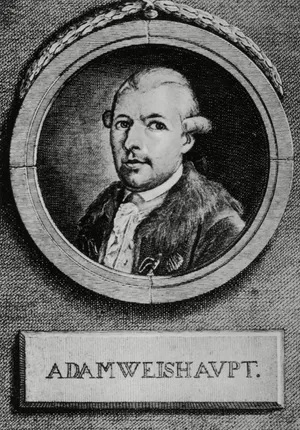

On May 1, 1776 — a date now more closely associated with labor movements than esoteric orders — a German law professor named Adam Weishaupt founded the Order of the Illuminati in Ingolstadt, Bavaria. It was a time when the Age of Enlightenment was in full swing, challenging monarchies, organized religion, and the authority of tradition. Yet amid this intellectual revolution, power structures remained rigid. Weishaupt envisioned a new architecture of influence, one grounded not in aristocratic birth or papal decree, but in reason.

The society he created was modeled after Freemasonry, structured in progressive degrees of initiation, secrecy, and symbolic ritual. However, while Freemasons championed moral uplift, the Illuminati actively sought to shape political discourse, guiding policy from behind the scenes through educated reformers embedded in key institutions.

Adam Weishaupt and his revolt against the Jesuits

Weishaupt’s antipathy toward the Jesuits was personal and philosophical. Raised and educated by the order, he came to see their grip on education and thought as suffocating. When Pope Clement XIV disbanded the Jesuits in 1773, Weishaupt seized the moment to push for secular, Enlightenment-based instruction.

His Illuminati was as much a protest against Jesuit dominance as it was a vehicle for rationalist reform. In an ironic twist, he mirrored many of the tactics he opposed — indoctrination, secret oaths, hierarchical structure — but aimed to reorient their ends.

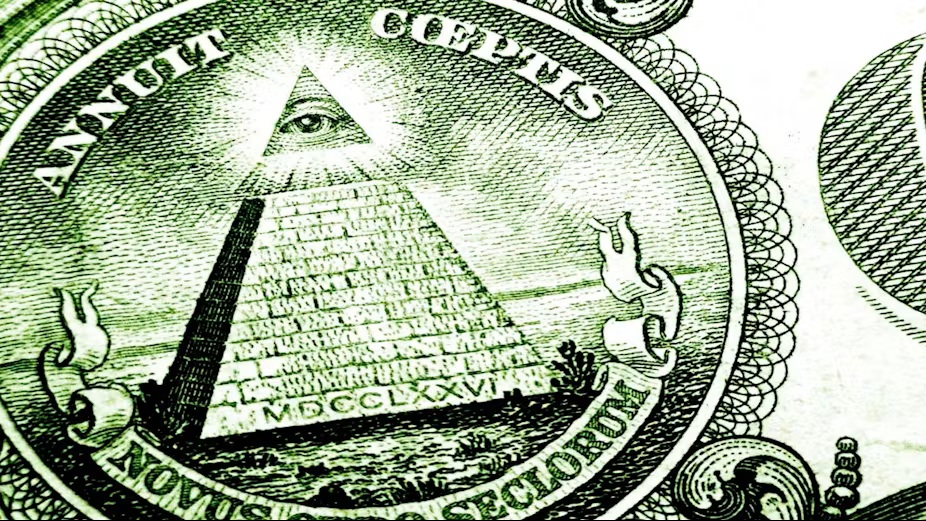

The goals, structure, and symbolism of the Bavarian Illuminati

The Illuminati’s aim was deceptively straightforward: to promote liberty, secularism, and rational government. But its methods were radical. Members operated under aliases, met in secret cells, and progressed through initiation grades that resembled those of esoteric brotherhoods.

- Minerval grade: The first entry point, inspired by the Roman goddess of wisdom.

- Illuminatus minor and major: Higher ranks who began shaping doctrine.

- Areopagites: The ruling council, privy to the order’s strategic aims.

This structure allowed for plausible deniability and vertical insulation, traits that would make the Illuminati both effective and ultimately vulnerable. In 1785, the Bavarian government, alarmed by rumors of sedition, suppressed the order, seizing documents and outlawing membership, which carried the penalty of death.

Historical members and families of influence

Despite modern associations with dynastic powerhouses like the Rothschilds or Rockefellers, the original Illuminati included members of the 18th-century European elite, particularly within Bavarian and Austrian nobility:

- Karl August, Duke of Saxe-Weimar

- Ernst II, Duke of Saxe-Gotha

- Count Metternich of Koblenz

- Count Stadion, an Austrian ambassador

These were not clandestine puppeteers but educated aristocrats, drawn to Enlightenment ideals. Their inclusion lent the order a degree of social gravity, though not necessarily the omnipotence later myths would ascribe.

Masks and myths: Ritual, performance, and power

There is no historical record suggesting that the original Illuminati wore masks. The notion likely stems from modern misinterpretations or conflation with Masonic or theatrical rituals, where anonymity served both symbolic and pragmatic ends.

In today’s conspiratorial imagination, masks represent hidden agendas, faceless authority, and elite deception. As performance theory reminds us, the mask doesn’t just hide; it transforms. The Illuminati myth, in turn, becomes a vessel for societal anxieties about surveillance, control, and truth.

The rise of Internet figures and the ‘Five-Headed Angel’

Enter @fiveheadedangel, an enigmatic Instagram figure who claims to be a “7th-generation Illuminati member.” In his videos, he tours European landmarks, references elite rituals, and speaks cryptically about intergenerational authority. His claims are unverifiable. His aesthetics are borrowed from meme culture, hip-hop esoterica, and the online occult revival movement.

What he does offer, however, is a mirror: a reflection of the human craving for mythic belonging in a hypermodern world. His followers don’t seek credentials; they seek coherence, a narrative that explains the inequalities and contradictions of contemporary life.

The power elite: Conspiracy or policy by privilege?

The concept of a global elite exerting influence across borders isn’t new. But to understand it requires distinguishing between conspiratorial cabals and structural power. As sociologist C. Wright Mills argued in The Power Elite, a triad of corporate, political, and military leaders exerts disproportionate influence, not through secrecy but through shared interests and institutional proximity.

Today’s policies often favor the wealthy, not due to secret rituals, but through lobbying, tax policy, campaign financing, and corporate lobbying. When people say “follow the money,” they are often just describing capitalism, not hidden councils. Still, the effect can feel conspiratorial.

Conclusion: Between enlightenment and enchantment

The original Illuminati was less a shadowy cabal than an ambitious experiment in elite-driven reform. Yet its mystique, aided by secrecy and suppression, has outlived its reality. It has become a cultural cipher, a mythos invoked to explain the opaque and unequal structures of modern life.

Whether it’s Weishaupt’s Enlightenment rebellion or the Instagram-age oracle claiming ancient lineage, the Illuminati persists because it satisfies a deep human hunger: the need to find order behind chaos, even if that order is sinister.

In the end, perhaps the real conspiracy is how effectively myths endure — not because they are true, but because they offer meaning when the world resists explanation.

Follow us on X, Facebook, or Pinterest