On a rainy Tuesday morning in Sydney, a group of physicists walked into their lab only to discover that, officially, their jobs had been relocated 12,000 kilometers away. Imagine showing up to a place where you’ve spent years trying to bend the laws of physics into something helpful, only to be told: “Surprise, you now work in Redmond, Washington.”

That’s essentially what happened when Microsoft shut down the University of Sydney’s Camperdown campus quantum research facility earlier this year. The company framed it as “consolidation,” a corporate term that roughly translates to: “We need all of this amazing, civilization-redefining science to happen where the U.S. government can keep a closer eye on it.”

And while most people scrolled past the headline (quantum computing has the unfortunate branding problem of sounding both too abstract and too sci-fi), what really went down here tells us a lot about the invisible systems shaping not just the future of computing, but global politics, labor, and even the way governments classify knowledge itself.

Why shut down a lab that was years ahead?

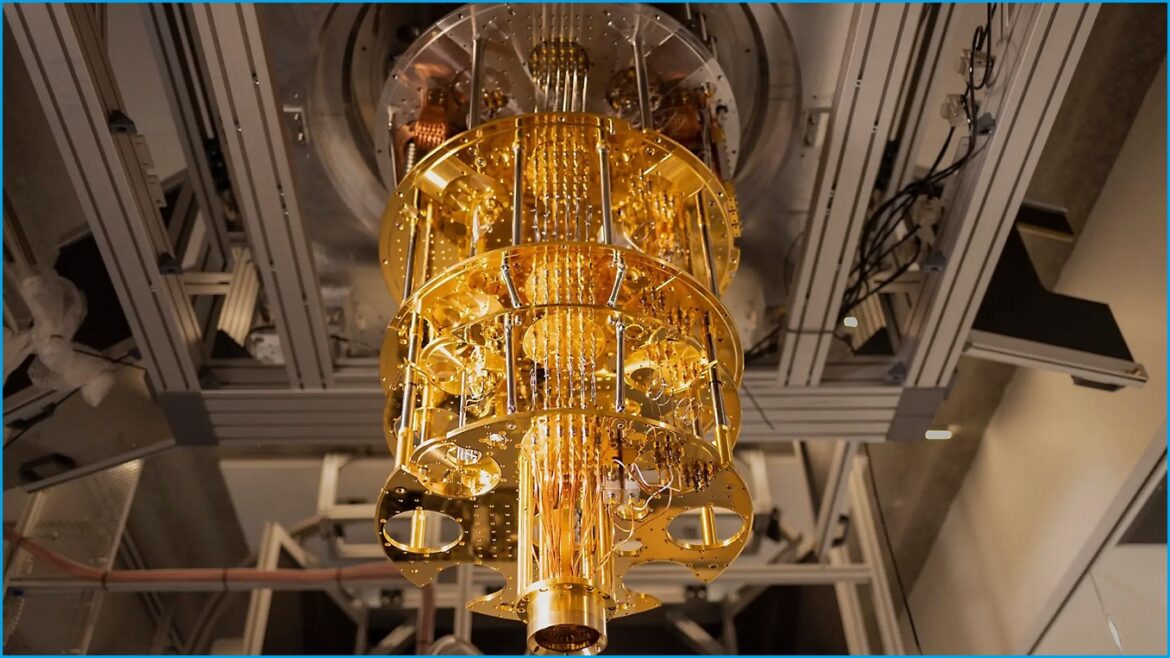

First, a little context: The Sydney team wasn’t just tinkering with qubits, those fragile, shimmering not-quite-bits that live at the bottom of refrigerators colder than space. They were tackling a problem that makes most quantum engineers sweat. Think about qubits as tiny cats. Each one needs its own personal food bowl, litter box, and blanket, all maintained at 15 millikelvin. Now imagine millions of cats. How do you keep them all happy without running 50 miles of wiring into the fridge? That’s the problem.

The Sydney group had developed a solution that resembled a cryogenic control chip, which could reside inside the freezer, directly adjacent to the qubits. It was like discovering you could put the cat food dispenser in the litter box — suddenly everything was compact, efficient, and didn’t involve miles of extension cords. Insiders suggested that this technology was years ahead of what IBM, Google, or anyone else was showcasing at the time. Which raises the question: Why would Microsoft pull the plug just as the lights were about to come on?

When science becomes geopolitics

Enter DARPA. The U.S. military has been quietly investing in quantum research through its “utility-scale quantum systems” program. Microsoft’s project was one of just two selected for the final phase. That’s not just a grant — it’s an invitation to the global chessboard. And once quantum computing is framed as “critical national security infrastructure,” everything changes.

The U.S. government tightened export controls, classifying quantum technologies under ITAR, the same regulatory regime that covers missile systems. This means that having your most advanced quantum lab operating out of Australia went from being a “cool international partnership” to a “potential liability” overnight. So Microsoft executives flew down, smiled politely, and offered the team a choice: move to Redmond with salaries so absurd that they could buy a Sydney house outright in a few years, or walk away.

The rebellion

Every single one of the 15 researchers said no. This is the part where the corporate script breaks. The scientists didn’t just scatter to different universities or quietly accept job offers elsewhere. They stayed together and started a new company, Emergence Quantum. If you want the rock-band analogy: It’s like the label dropped Radiohead in the late ’90s, and instead of breaking up, the band decided to self-release Kid A and change the entire music industry.

Within a year, Emergence Quantum published a paper in Nature proving their cryogenic control chip could work with fundamental silicon qubits without degrading performance. In other words, the breakthrough didn’t vanish — it just left Microsoft’s walls.

The invisible characters: chips, patents, and NDAs

Now, here’s the part where invisible systems take the stage. Microsoft still owns the intellectual property from seven years of Sydney research, including patents, designs, and the legal framework. What they don’t own anymore is the tacit knowledge — the “muscle memory” of the scientists who spent their lives making the thing actually work.

This is where quantum computing begins to resemble a messy divorce. Microsoft has the house, the car, and the family dog. Emergence Quantum has the Spotify playlists, the inside jokes, and the knowledge of which pipes always clog. In the tech industry, tacit knowledge is often the most valuable asset.

The culture of ‘shut up until you win’

If you’re wondering why you haven’t seen breathless headlines about this, it’s because Microsoft has mastered the art of silence. IBM and Google show off noisy qubits like proud parents with Instagram accounts. “Look, 100 qubits! They can almost factor small numbers before collapsing into chaos!” Meanwhile, Microsoft keeps its cards so close to its chest that you wonder if it even believes in qubits at all.

However, in February 2025, they announced the Majorana One, a prototype chip featuring eight topological qubits. Physicists at the American Physical Society meeting called the evidence “unconvincing” and “like a Rorschach test.” Yet Microsoft insists it’s on track for a million-qubit machine by 2027. This is the tortoise strategy: Don’t sprint ahead with flashy demos. Crawl steadily, say very little, and by the time the hare looks back, you’re already at the finish line.

Workplace dynamics, quantum edition

Here’s where I can’t resist imagining the people involved, because technology stories are always human stories in disguise.

- The Sydney researchers: Picture a group of highly caffeinated physicists in hoodies, staring at oscilloscopes and dilution fridges, suddenly faced with the option of trading the beaches of Bondi for the drizzle of Seattle. Their collective “nope” was less about money and more about identity.

- The Microsoft executives: Two people in suits flying down to Australia with contracts thicker than Sydney phone books, convinced that loyalty and housing markets could overcome physics envy.

- The U.S. government official: Somewhere in Washington, a mid-level bureaucrat responsible for quantum export compliance who suddenly realized he had power over the fate of technologies he barely understood. (“So… wait, a qubit is like a cat that can be both asleep and awake?”)

The comedy writes itself, but the consequences are dead serious.

Why this matters

Quantum computing isn’t about faster Netflix recommendations. It’s about breaking encryption, modeling complex chemistry, and possibly training AI models at speeds that today’s GPUs can only dream of. Whoever controls it controls the infrastructure of intelligence itself. The Sydney lab was building the connective tissue: the control systems that make quantum computers scalable. Lose that, and you don’t just lose a few researchers — you risk losing the layer that makes the whole field practical.

For Australia, the timing was brutal. Just as the government rolled out a billion-dollar national quantum strategy, its most advanced homegrown team was effectively exported. For Microsoft, it may have been a chess move — retain the patents, let the people go, and maybe re-engage later through licensing. For the rest of us, it’s a reminder that the next phase of computing is being shaped less by open collaboration and more by geopolitics, corporate secrecy, and patent law.

The unsettling twist

Was this a shutdown, or a quiet transfer of knowledge into safer, geopolitical hands? Or maybe a Trojan horse: Let Emergence Quantum run free, innovate quickly, and then scoop up the results later under existing patents. The truth may be somewhere in the middle, and that’s the most unsettling part. While we debate whether our phones are listening to us, the actual infrastructure of intelligence — the future of computing itself — is being redrawn in secret labs, through government contracts, and in startup rebellions. And if history is any guide, by the time we see the press release, the real breakthroughs will already be five years old, tucked behind NDAs, waiting for the right moment to surface.

Conclusion: the invisible fridge humming beneath it all

Quantum computing lives inside refrigerators colder than outer space. That detail always feels metaphorical to me: humanity’s next leap forward locked away in a humming box that most of us will never see, controlled by forces we barely understand. Microsoft’s Sydney shutdown wasn’t just about moving jobs. It was about who gets to decide the terms of that leap: corporations, governments, or the scientists themselves. For now, the fridge continues to hum, whether in Redmond or Sydney. And somewhere in between, the future of computing is quietly being rewritten — not in code, but in contracts, cultures, and choices about who gets to own the next paradigm.

Follow us on X, Facebook, or Pinterest