In ancient times, a mythological Chinese ruler, the first Yan Emperor Shennong, became a deity in Chinese folk medicine. As the population grew, human hearts grew less pure, and the natural environment deteriorated, leading to the rise of disease. Shennong personally tasted hundreds of herbs, used them to cure diseases, relieve suffering, and save lives, and became revered as the forefather of herbal medicine.

The primeval forest of Shennongjia, in Hubei Province, is said to be the place where Shennong gathered herbs, identified 365 medicinal plants, and compiled Shennong’s Herbal Classics, which has been passed down to this day. This book, together with the Inner Canon of the Yellow Emperor, The Yellow Emperor’s Canon of 81 Difficult Issues, and Treatise on Cold Damage and Miscellaneous Diseases, became the four great classics of Chinese medicine and laid the foundation for treating illness with herbal remedies.

In modern times, with the influx of Western medicine and the so‑called integration of Chinese and Western practices, traditional Chinese medicine has faced tremendous challenges. Nevertheless, in mainland China, there are still many hereditary practitioners scattered among the people — reclusive masters who travel widely, offering healing and saving lives. I have personally encountered three folk doctors with outstanding medical ethics and remarkable skills; below are their stories.

A mysterious doctor from Shennongjia

A doctor studied medicine from childhood and took his master’s degree in Shennongjia in the 1970s. According to reports published in the Huangshi Health News, in the early 1980s, he was invited to Beijing’s Zhongnanhai (a compound which houses the offices of the Chinese Communist Party’s leaders) to treat a veteran Red Army soldier, who had suffered a stroke. He was noticed by the wife of Hu Yaobang, then the Communist Party’s General Secretary, who asked him to stay in Beijing. Yet, he found an excuse to return to Wuhan, Hubei. I questioned him on why he did not seize such a good opportunity, but he smiled and did not respond.

At that time, a friend’s father suffered frequent strokes, with no effective cure. After I introduced him to the doctor, the strokes disappeared for 10 years. The doctor only charged 35 yuen per diagnosis, and the patient would then take his prescriptions to a herbal pharmacy. The prescriptions were different each time: the first was a purgative to detoxify, the second a strong medicine to attack the root of the illness, and the third a tonic to restore the body. Ten years later, the old illness recurred, but when the patient looked for his doctor, he was unable to locate him.

An illiterate doctor known as ‘Five‑Finger Plum Blossom’

In the summer of 2003, my wife and I joined a tour group to Jiuzhaigou in Sichuan. On our way there, we stopped in Wenchuan, where our tour guide led us to a large herbal medicine market with stalls featuring famous folk doctors offering consultations. Some diagnosed by feeling a person’s pulse with one hand, others with both, and some examined the color of their fingernails. Practitioners only earned money from selling medicines, so many tourists sought diagnoses out of curiosity.

After browsing for a while, we queued at the stall of a female doctor known as “Five‑Finger Plum Blossom,” just behind a middle‑aged man. She examined his left hand’s fingernails and described ailments in various parts of his body, asking whether he wanted a cure. The man accepted a prescription and bought the herbs in the market. Doctor “Five‑Finger Plum Blossom” also told him, “Once you take the herbs listed in these prescriptions, you won’t need to dye your hair any longer.” I asked the patient whether her diagnosis was accurate, and he replied, “If it weren’t, why would I spend so much money on her expensive herbs?”

Next, the doctor examined my wife’s fingernails on her right hand; she perfectly described her health issues, personality, and temperament. She even prescribed her a beauty formula, which she has preserved to this day. Doctor “Five‑Finger Plum Blossom” introduced herself, saying: “I never went to school and cannot read a single character. Later, in order to practice medicine, I learned to recognize and write words. I am of Qiang ethnicity, and my medical knowledge was passed down orally from my elders.”

After lunch in Dujiangyan, I met the middle‑aged man again and asked if he had dyed his hair. He explained that he was a middle school teacher from Nanyang, Henan, and confirmed he had done it during the summer holidays. I remarked, “Ordinary people would never notice your hair is dyed. How did she know it, considering she didn’t even look up while diagnosing you?”

It also seems that this female doctor had remarkable success treating diabetes without requiring lifelong medication dependence, as in Western medicine.

A ‘half‑Immortal’ doctor with the ability to diagnose and treat remotely

At our workplace, a young driver developed corn on his foot, commonly called “meat thorns.” He tried many methods — Western and Chinese medicine, as well as various folk remedies — but none worked. Strangely, the corns on the sole of his foot were arranged in the shape of the Big Dipper.

Later, through an introduction, his mother found a local female doctor known as a “half‑immortal.” She did not openly treat patients, nor did she accept gifts or money, but after repeated requests from the woman, she agreed to look into the matter. At the time, the driver himself was on a business trip in Tianjin.

In a phone call, the “half‑immortal” asked him whether, as a child, he had ever gone to a certain place and stepped on incense used for worship. He admitted that, mischievous and ignorant as a child, he had indeed done such a thing. That evening, she instructed him to stay in his hotel room while she treated him remotely. Soon after, the corn on his foot disappeared completely.

Today, despite those CCP-appointed scholars influenced by “evolution theory” and “atheism” — including figures such as He Zuoxiu and Fang Zhouzi — who disparage traditional Chinese medicine as “pseudo‑science” and slander it as “the most successful fraud in three thousand years,” it cannot be denied that countless ancient records describe miraculous doctors, who cured diseases and revived patients, including Bian Que, Dong Feng, Hua Tuo, Zhang Zhongjing, Sun Simiao, and Li Shizhen.

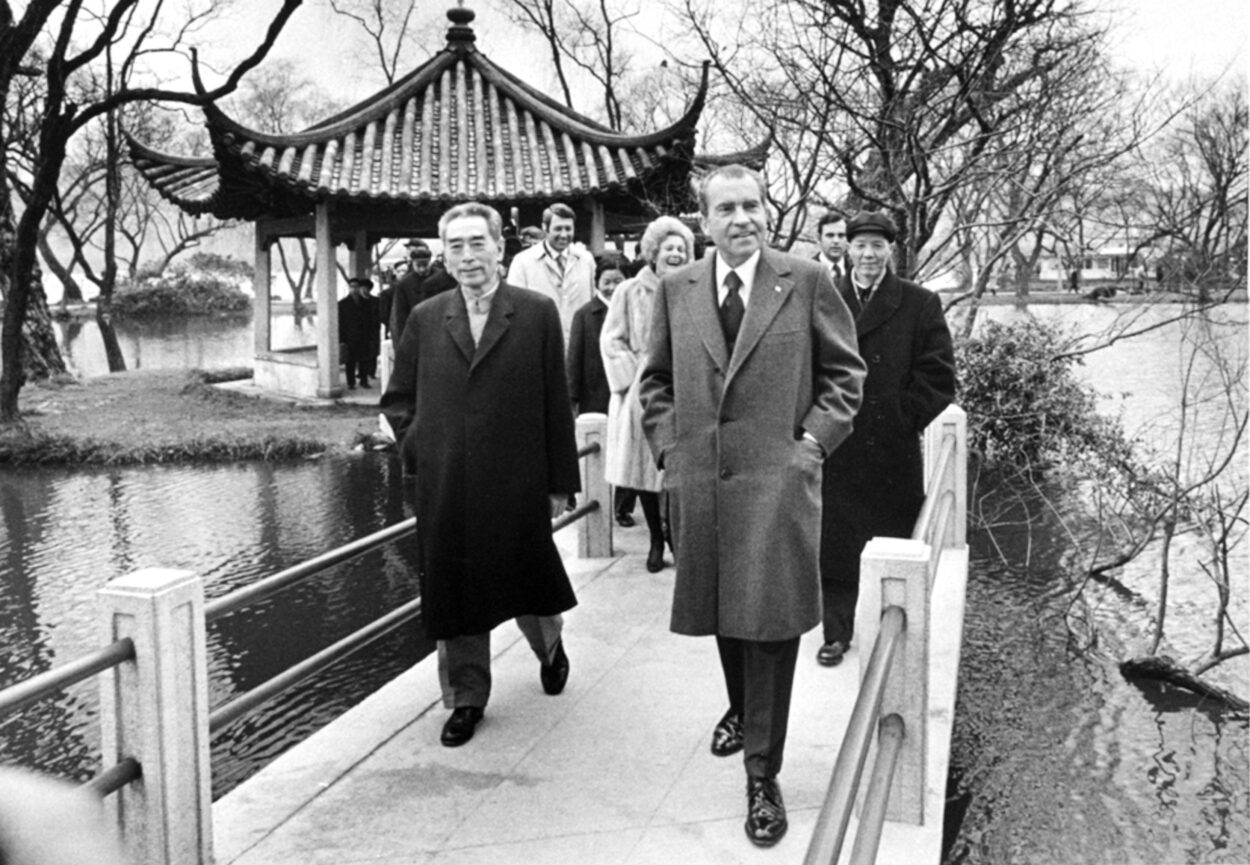

In 1972, when former U.S. President Nixon visited China, Premier Zhou Enlai accompanied him to observe acupuncture. A thin silver needle was gently inserted into a patient’s hand, connected to an electrical current, and then surgery was performed. The patient, without anesthesia, showed no pain, astonishing Nixon. Confronted with the marvel of Chinese medicine, Nixon asked the doctor, “What are meridians? What functions and characteristics do they have?” Embarrassingly, neither that doctor nor any other physicians present could respond.

Shortly after Nixon’s visit, Zhou Enlai convened experts from medical schools, the Chinese Academy of Sciences, and Peking University to discuss Nixon’s question. He urged them, “We must quickly clarify the essence of meridians. Do not let the theory of meridians in Chinese medicine bloom inside the wall, but bear fruit outside.”

It was under such circumstances that a call for the revival of traditional Chinese culture arose, sparking an unprecedented “qigong fever” across China.

Since ancient times, sayings such as “medicine and the Way are connected” and “great virtue carries all things” have emphasized that extraordinary skills could be passed down only to those of high moral character. As the universe follows cycles of formation, stasis, decline, and destruction, and as human morality decays and minds become corrupted, many ancient doctors chose to take their lifelong skills to the grave rather than pass them on to unworthy successors. Thus, truly holistic hereditary medical techniques were lost, gradually replaced by Western medicine, which often treats symptoms but not root causes.

It is well known that extraordinary illnesses require extraordinary methods. Once the accumulated karmic burden of disease surpasses the capabilities of modern medicine and drugs; once widespread epidemics reappear; and once rulers, like Duke Huan in the story of “Bian Que Meets Cai Huan Gong,” conceal their illnesses and refuse treatment — while calling Chinese medicine and qigong ‘superstition’ — perhaps the great elimination of humanity foretold in prophecies will begin. The current outbreak of African swine fever in mainland China is another warning bell.

The Huangdi Neijing states: “The superior doctor treats a disease before it arises; the middling doctor treats a disease after it appears.” The Essential Prescriptions Worth a Thousand Gold says: “The superior doctor heals the nation; the middling doctor heals people; the inferior doctor heals an illness.”

A common saying goes: “Illness is seventy percent mental and thirty percent physical.” In other words, wise rulers who govern well understand the sages’ teaching that “spirit and matter are one.” Human physical illness stems from inner psychological issues; the downfall of a nation likewise arises from moral decay. Only by promoting national essence, returning to tradition, purifying hearts, elevating morality, and preventing problems before they occur can there be peace for the nations and prosperity for the people.

Translated by Cecilia and edited by Laura Cozzolino

Follow us on X, Facebook, or Pinterest