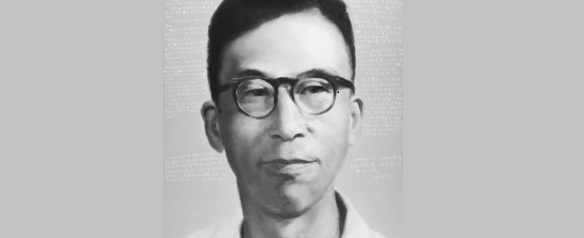

Gu Zhun (July 1, 1915 – December 3, 1974), born in Shanghai, China, and also known as Zheyun, was a contemporary Chinese scholar, thinker, economist, accountant, and historian.

In 1952, Gu Zhun advocated tax collection strictly in accordance with statutory rates and opposed campaign-style taxation. As a result, during the “Three-Anti Campaign,” he was stripped of all Party and public positions. Gu Zhun’s children announced that they were severing ties with him.

In 1965, Gu Zhun was again labeled a rightist for allegedly organizing a “reactionary clique.” During the subsequent Cultural Revolution, he endured even more brutal persecution, both physically and mentally. Under immense political pressure, his wife Wang Bi — who had shared his hardships for over 30 years — was forced to file for divorce. In April 1968, unable to bear the persecution, she took her own life in despair. Gu Zhun’s five children severed all ties with him and cut off all contact. After Gu Zhun was diagnosed with terminal cancer, the head of the Institute of Economics took pity and wrote to his youngest son, urging him and his siblings to return and take care of their father.

Gu Zhongzhi, Gu Zhun’s youngest child, replied: “No, absolutely not! Between devotion to the Party and hatred toward Gu Zhun, there cannot be any ordinary father-son affection… We chose to be loyal to the Party and to Chairman Mao, and to sever all ties with Gu Zhun. We believe this is the right thing to do and do not consider it excessive.” In the eyes of his offspring, Gu Zhun was “a demon and a monster,” therefore, everyone shunned him.

While children in China regarded their parents as “class enemies,” the most heartwarming story unfolded on the Taiwan side of the strait. The most significant figure in Lei Meilin’s Heart was her father, Lei Zhen.

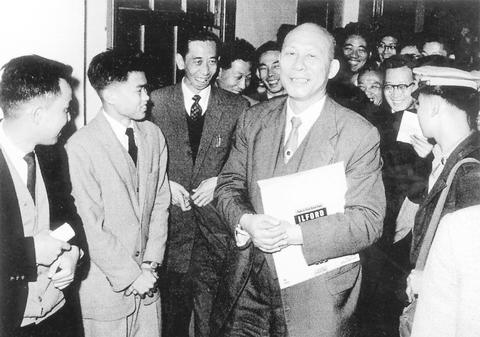

In the 1960s, at a journalism college in Taiwan, a young woman named Lei Meilin wrote an essay for her military training instructor; the title was “Who is the greatest person in your heart?” Lei Meilin’s work did not mention Sun Yat-sen, the father of the Nation, nor Chiang Kai-shek, the president. She declared that the greatest person in her heart was her father, Lei Zhen.

Lei Zhen, publisher of the magazine Free China, had angered Chiang Kai-shek by advocating for freedom and democracy and promoting the formation of opposition parties in Taiwan. The Kuomintang authorities fabricated charges, arrested Lei Zhen, and sentenced him to ten years in prison. After Lei Meilin submitted her essay, her instructor’s face flushed crimson. He stomped his feet in class, berating the girl as “shameless” and even threatening her expulsion. He snarled: “It’s either you go, or I go!” The journalism college convened three consecutive days of meetings over this incident. As a result, the instructor was dismissed! The school’s president was the renowned journalist Cheng Shewo.

Lei Meilin and Cheng Shewo stood up against Kuomintang’s authoritarianism, which had led the masses to view Lei Zhen as a menace. Their humanity and integrity shone through the darkness and served as a positive example for future generations of Chinese students and teachers.

Today, numerous articles reflect on the Cultural Revolution, expressing repentance, yet most attribute that dark era to a single leader. Clearly, this is just a cover for the ugly truth.

Contemporary education emphasizes character development, but it rarely touches children’s souls. Let us consider how Chinese educators teach gratitude toward parents: students are told that a good way to show appreciation is to study diligently and earn good marks. Gratitude toward parents is reduced to a few exam scores — such a minimization is shallow and only scratches the surface of this principle.

To guide young people in developing their character, teachers should possess greater humanistic literacy and provide appropriate role models. Lei Meilin’s selflessness is an inspiration to others, whereas Gu Zhun’s children’s lack of integrity and familial affection serves as a warning and reveals the dark side of the Kuomintang.

Translated by Audrey Wang and edited by Laura Cozzolino

Follow us on X, Facebook, or Pinterest