The concept of the Carl Jung Shadow has never felt more relevant than it does in the age of social media and algorithmic feeds. First explored in depth during Carl Jung’s psychological descent, as recorded in The Red Book, the Shadow denotes the hidden aspects of the personality that we repress, deny, or fail to recognize. Today, these unseen traits are no longer confined to the unconscious — they are reflected back to us through curated digital environments that amplify our triggers, biases, and emotional blind spots.

The Carl Jung Shadow, and the algorithmic mirror of modern life

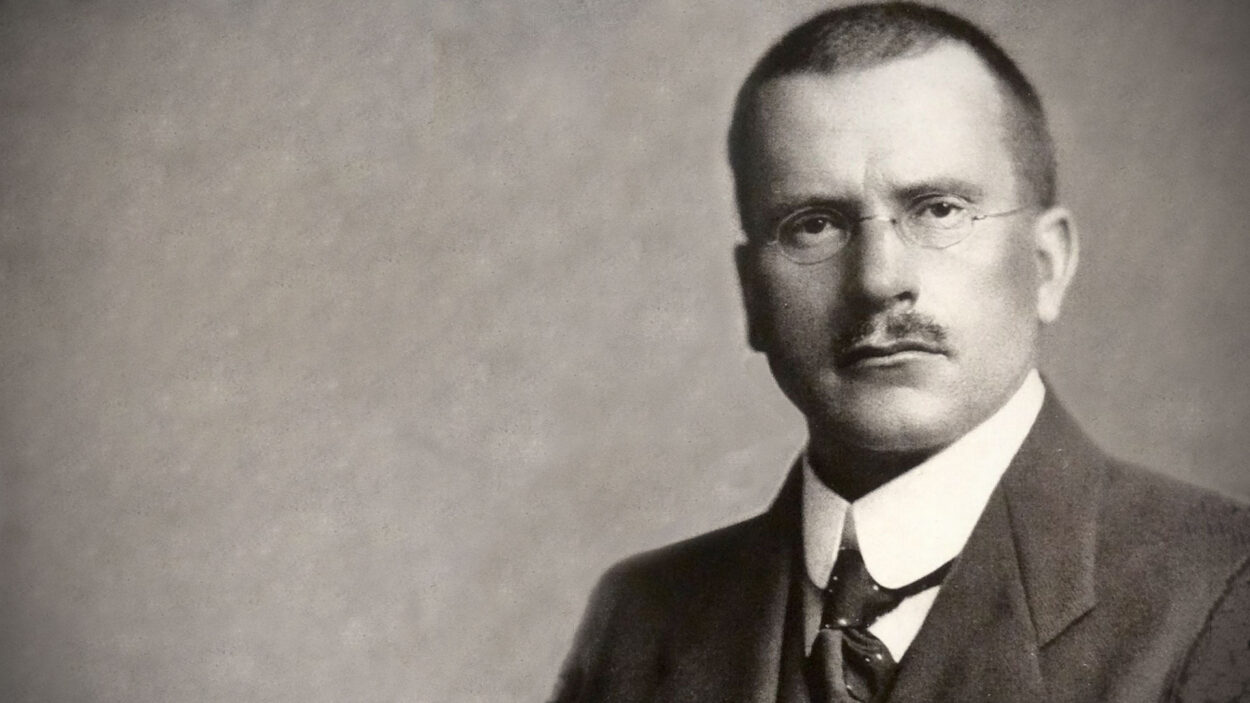

In 1913, a respected Swiss psychiatrist began to fear he was losing his mind. Carl Jung was thirty-eight years old, professionally successful, and newly estranged from Sigmund Freud, the intellectual father he had publicly defied. Then the visions came. Europeis flooded with blood. Civilizations collapsed. Strange figures appeared in waking dreams. Carl Jung, who had built his reputation on disciplined inquiry, found himself haunted by images that felt older than reason. He did not medicate them away. He did not bury them beneath work. Instead, he turned toward them.

What followed would become The Red Book — a massive, red leather-bound manuscript filled with painted mandalas, mythic dialogues, and a record of his descent into what he would later call the unconscious. For years, the book remained hidden from the public, whispered about as a kind of forbidden gospel of modern psychology. When it was finally published in 2009, readers encountered not a clinical treatise, but a map of inner terrain. At the center of that terrain stood a figure Carl Jung would name the Shadow.

Today, more than a century later, the Shadow has found new architecture in which to operate. It lives in our feeds, in our comment sections, in the invisible mathematics that decide what we see next. It thrives in the hall of mirrors we call social media.

What is the Shadow?

In Jungian psychology, the Shadow denotes aspects of the self that we repress, deny, or fail to recognize. These traits are not necessarily immoral or destructive. They are simply incompatible with the image we wish to present to the world. We curate ourselves long before we curate our profiles. As children, we learn which emotions are rewarded and which are discouraged. Anger may be labeled as disrespectful. Sensitivity may be dismissed as weakness. Ambition may be considered selfish. Over time, we push these traits out of sight — not because they disappear, but because they complicate belonging.

The Shadow becomes a private archive of disowned qualities. It can contain rage, envy, pride, and insecurity. But it can also hold vitality, creativity, and assertiveness — traits that were once discouraged and therefore hidden. The Shadow is not evil; it is unlived. Carl Jung’s insight was not that humans possess darkness. That was hardly novel. His insight was that what we refuse to see in ourselves does not vanish. It reappears in disguised form. Most often, it reappears in others.

Projection: The Shadow in public life

Projection occurs when we attribute to others qualities we cannot accept in ourselves. We see arrogance everywhere, except in our own certainty. We condemn intolerance without examining our own rigidity. We criticize selfishness while overlooking our subtle forms of self-interest.

Projection is psychologically efficient. It spares us the discomfort of self-examination. It also intensifies emotion. Nothing outrages us more than a trait that resembles our own denied impulses. In earlier eras, projection operated within smaller communities. Today, it scales globally.

Social media has compartmentalized society into personalized realities. Each user inhabits a tailored environment shaped by algorithms designed to maximize engagement. Engagement, in turn, is driven by attention — and attention is most reliably captured by what provokes us. We linger on what triggers us. We comment on what unsettles us. We share what confirms our grievances. The algorithm notices.

I once conducted a small experiment. For several days, I intentionally paused from engaging with a specific type of content — reacting, commenting, sharing. Within hours, my feed began to change. By the second day, it had narrowed into a corridor of similar themes. By the third, it felt as though the world itself had shifted, as if everyone was preoccupied with the same issue. In reality, the shift was internal, reflected in the code. The algorithm had found my Shadow’s fingerprints.

The intimate theater of the feed

Social media is often described as public, but it functions psychologically as private. The screen creates a sense of intimacy. Alone with a device, users engage with material they might hesitate to discuss openly. They reveal preferences, frustrations, curiosities. They search for validation, belonging, and recognition. This environment is fertile ground for projection.

When a person struggling with self-worth encounters content that externalizes blame — assigning fault to institutions, groups, or cultural forces — it can feel stabilizing. “I am not the problem,” the narrative suggests. “The system is.” When others echo this sentiment, the relief deepens. Community forms around shared grievance. There is genuine comfort in discovering that others feel the same dissatisfaction. It reduces isolation. It affirms experience. In its healthiest form, this can foster solidarity and constructive dialogue. But it can also create a loop.

An unstable or fragmented personality may seek out content that reinforces existing insecurities. Algorithms, indifferent to psychological nuance, respond by supplying more of the same. The user scrolls longer. The system optimizes. What began as mild discontent can intensify into conviction. “I am okay because others are like this,” becomes, “We are right because we feel this.” The Shadow, once private, becomes collective.

The collective Shadow in digital form

Carl Jung warned that groups possess Shadows just as individuals do. When a community defines itself by virtue alone, it becomes blind to its capacity for exclusion or aggression. In the digital age, identity clusters form rapidly. Political tribes, cultural movements, niche subcultures — each can develop narratives that emphasize righteousness while displacing doubt. The algorithm does not create these dynamics, but it accelerates them. It rewards emotional intensity rather than introspection. A calm, reflective post rarely competes with a charged denunciation.

The result is a fragmented landscape in which projections bounce between communities like light between mirrors. Each side perceives the other as the embodiment of what it despises. Rarely does anyone pause to ask: Why does this particular trait provoke me so deeply? The question itself feels threatening. It shifts attention inward.

The positive Shadow

It would be misleading to describe the Shadow solely in negative terms. Carl Jung emphasized that disowned qualities can be constructive. A person raised to be agreeable may suppress assertiveness. A person taught to value logic may repress emotion. When these traits emerge, they can broaden personality rather than narrow it.

In digital spaces, this dynamic can also unfold. A mature and stable individual may encounter content that reflects unacknowledged aspirations — creative expression, disciplined thinking, acts of generosity. The algorithm amplifies these interests, reinforcing growth. The difference lies not in the technology but in the psyche that engages with it. A grounded personality can use social media as a mirror for self-development. A fragmented one may use it as a refuge from self-confrontation.

Carl Jung’s method: Turning toward the Shadow

Carl Jung’s response to his inner upheaval was neither suppression nor indulgence. He practiced what he later called active imagination — consciously engaging with symbolic material from his unconscious. In The Red Book, he recorded dialogues with figures who embodied aspects of his psyche. He did not treat them as literal beings, nor did he dismiss them as nonsense. He listened.

Shadow work, in Carl Jung’s understanding, requires similar listening. It begins with noticing emotional intensity. Why does this post provoke me? Why does this group’s behavior irritate me disproportionately? What trait am I condemning, and where might a trace of it exist within me? The aim is not self-blame. It is self-recognition. Acknowledging envy does not imply acting destructively. It may reveal an unpursued ambition. Recognizing anger does not justify aggression; it may indicate a boundary violation. The Shadow’s energy, once named, can be redirected. Integration reduces projection.

Immunity in the hall of mirrors

If social media is a hall of mirrors, psychological immunity depends on discernment. Not every reaction is evidence of truth. Some are evidence of resonance with disowned parts. Practical steps toward resilience might include:

- Pausing before reacting to triggering content.

- When asked about personal experience, the content addresses it.

- Diversifying one’s information environment intentionally.

- Engaging in offline reflection that grounds identity beyond the feed.

Artificial intelligence adds another layer. Conversational systems learn from user input, tailoring responses to preferences. They can serve as amplifiers of belief or as tools for exploration. Used passively, they may reinforce existing biases. Used reflectively, they can challenge assumptions.

The responsibility remains human

Carl Jung believed individuation — the process of becoming whole — requires confronting the Shadow rather than projecting it outward. In a digital ecosystem optimized for engagement, this task becomes more demanding rather than less. The algorithm thrives on unconsciousness. It rewards speed, not self-examination. But it cannot compel reflection or prevent it.

The Shadow is not a technological invention. It is a human constant. What has changed is the scale and speed at which it circulates. Our private disowned qualities now find public expression within seconds. Outrage becomes content. Insecurity becomes narrative. Belonging becomes brand.

Yet the same mirrors that distort can also clarify

When we notice the pull of certain themes — when we recognize how easily a feed can be shaped by lingering attention — we gain insight into ourselves. The experiment reveals not only the algorithm’s design, but our own vulnerabilities. Carl Jung descended into his inner world not to escape reality, but to understand it. He returned with a conviction: what we refuse to see in ourselves will unconsciously shape our world.

In the age of endless scrolling, that insight feels less like philosophy and more like instruction. To navigate the hall of mirrors without losing ourselves, we must be willing to ask a quiet, unsettling question whenever emotion surges across a screen: What part of me is being reflected here? The answer may not flatter. But it may be free.

Follow us on X, Facebook, or Pinterest