The following excerpt (Part 2) is from the novel The Shanghai Friendship Store* by Susan Ruel and is a continuation of the previous article (Chapter 1). The novel chronicles the experiences of a small foreign community living in Shanghai in the 1980s (the heyday of Friendship Stores). Nowadays, only a few of these stores remain open, notably in Beijing, Shanghai, and Guangzhou. These modern Friendship Stores even feature Western franchises like Starbucks, Baskin-Robbins, etc.

A Chinese Eleanor Rigby (The Shanghai Friendship Store — Chapter 1, Part 2)

A few years later, long after my time working in Shanghai had ended, I was back on the other side of the world. I’d come at last to New York City, where so many end up. For surreptitiously filing some news stories as Shanghai stringer for the International Press — including an exclusive interview with Irini, the Greek “expert” whose Chinese fiancé was arrested for consorting with foreigners — I got hired by IP on the West Coast and eventually promoted to their global news desk in New York.

There I found myself a hated newcomer in that peculiar circle of hell devised for wire-service reporters who move up in the ranks. My new editing role prevented me from socializing much — or even being outdoors. I noted that some of the biggest stories in the world — hijackings, bombings, and other tales of what the news business glibly deems “tragedy” — somehow seemed drained of almost all life once they made it onto the wire. And, since I was spending most of my waking hours in a dusty newsroom, at times Manhattan itself felt reduced to the dimensions of a small town, where I carried out the same rituals day by day. Only the date on the news wire inched forward relentlessly.

I came to better understand the last verse of the old Beatles’ song A Day in the Life:

“I read the news today, oh boy

4,000 Holes in Blackburn Lancashire

And though the holes were rather small

They had to count them all

Now they know how many holes it takes to fill the Albert Hall…”

I learned to craft a news brief on the latest Mount Everest climb out of a stream-of-consciousness dispatch from Katmandu, composed according to the prose rules of Nepali. I learned to make “news emergency” overseas calls to Dhaka, yelling into the phone to get the latest confirmed death toll figures on a typhoon.

And I finally underwent my own version of what the Chinese called Political Study, learning more than I wanted to know about the backstabbing and favoritism that pervade many newsrooms — so similar to the emotional dynamics of large, unhappy families. On the graveyard shift, we would-be foreign correspondents were consumed by restlessness. The same qualities of curiosity and extroversion that propelled us into journalism in the first place now tormented us the most, as we paid our dues by being chained to the news desk as editors before getting sent overseas. It felt unhealthy to sit motionless over a keyboard all night, monotonously “turning” stories for the p.m. cycle, then going home to tiny apartments we could barely afford, to lie quiescent and wakeful all day, alert to the sound of a ringing phone and the chance of a better assignment.

One morning after working the deep overnight, I arranged a breakfast interview with a Bard College professor whose specialty was Chinese politics. My plan was to draft some sort of “enterprise” think piece, based on our conversation about his new book. When we met in the reception area at IP headquarters, he introduced me to his research assistant, and I gazed into the doomed, orphaned eyes of Mrs. Wren. It felt like a resurrection of sorts — and one of the stranger coincidences of my life.

She looked nearly the same, apart from her new permanently waved curls and the bright orange down coat that had replaced her worn-out old Mao jacket. Her eyes had the same preternatural brightness, a badge of insomnia. In those eyes I still saw a core of abandon so blighted that it made me think of nuclear waste.

Then she walked, exhibiting a pitiful limp caused by poorly set bones that had healed improperly. As she dragged a comb through her hair in the ladies’ room before we had breakfast, I got a good look at her and had to hide my tears.

“You’re looking good,” I lied, biting my tongue to keep from telling her that we’d been told she was dead.

“People say I am thinner now than before my fall,” she said wistfully. “Part of me wants to die. I don’t want to be the only one left alive,” she said in a normal tone, as if this were a fitting topic for small talk.

Over breakfast, she recounted how she had come to the United States. She’d been so badly injured by her “fall” — as even I was soon lulled into calling it — that she was admitted to Shanghai’s best hospital.

“On my ward, 75 women used one cold-water faucet. Using this faucet, I contracted an infection. I broke out in a rash that Chinese doctors diagnosed as measles,” she said in her slightly bookish English. “I knew it was nothing of the sort, and so I appealed to my sister to help me get to the United States on medical grounds.”

She had a sister in the States? This was new information. She talked on, explaining how her older sister (who’d flouted the ideal of filial piety by failing to come home and nurse their dying parents) finally got her out of Shanghai.

I heard the long, twice-told jeremiad: the old mother driven mad, the family mansion sacked, the ancient library ruined, the scroll paintings torn, the Richelieu pearls lost, the husband dead of self-murder, the child she never had (“Who would dare to bring a baby into the world at such a time?“), and finally, the elder sister. By this time, the sister was a professor at a prestigious U.S. university who said not: “Forgive me. I knew not what I was doing,” but, instead: “The Cultural Revolution was an inevitable phase of history. In the final analysis it was good for China.”

There was more: Mrs. Wren’s long, confessional poem, an elegy to the old mother who went without food in order to leave the family’s last remaining fen to the faithful servant, who leaned her head back on the soiled, Red Guard-torn pillows and dreamed that she was at an academic seminar in Canada or a symposium on European history in London; and to Mrs. Wren herself, covering with blankets the sleeping forms of a half-dozen Red Guards, moments after they’d collapsed in exhaustion after pouring gallons of sewage on the polished wood floors and rosewood furniture of the Wren mansion.

“I told myself they are children of God,” she said. “The family is bankrupt, and the children are dead,” she said.

“Pardon me?”

“The family is bankrupt, and the children are dead. A Chinese expression that means every terrible thing that could happen has already happened. It cannot but get better.” There might have been more, but the professor, her benefactor, the professor, wouldn’t hear of it. He slammed his fist on the table.

“I forbid any more talk of family matters. And my taboo extends to subjects like poetry, religion, and volunteer work,” he roared, with a savagery that seemed only partly feigned.

He explained to me, as if Mrs. Wren weren’t even there, that she was eking out a living by helping him with translations for his research and by teaching Chinese. It was hard to imagine her making easy conversation with students, let alone facing them day after day with the tragic mask of her face.

Sure enough, he complained that for the past few years, she seldom left the tiny garret he’d help her rent in a suburban college town a bit far from the city. She’d become a kind of Chinese Eleanor Rigby. I felt he lacked compassion for her, although without him, she probably couldn’t have survived.

“I’ve got to get you out of that attic!” I said, too bluntly. “Come and spend a weekend at my apartment here in Manhattan. We could go to Chinatown, to museums. I’d love to take you around the city.”

“Oh, no, I could never impose on your hospitality in that way,” she said. But the professor insisted that she come.

Mrs. Wren arrived by bus on a Saturday morning. A gloomy rain falling on New York reminded me of Shanghai. I met her at Port Authority station, and we chatted self-consciously on the way to my apartment. I had to force her to let me help with her suitcase. It frightened me a little that she had no memory whatsoever of having given small Christmas gifts to me and a few other “experts” back in Shanghai, Even when I showed her the tiny clay figurines of Chinese ethnic minorities that she’d given us, she had no recollection of doing so.

I asked to read her long, autobiographical poem about the Cultural Revolution. Despite its stilted style, the images were unforgettable — a fact I was grateful for when she abruptly asked me to return her manuscript as soon as I finished reading it. She refused to let me make a copy.

Our first stop that day was in Chinatown: a restaurant known for its crabs, whose legs and torsos she chewed on delightedly for a long time. While we ate, she spoke almost lucidly at times about the fact that she still had a “secure job” to go back to in China, were she ever reduced to penury in old age here in the United States. This worry obsessed her. The possibility of returning seemed filed in the back of her mind as a kind of final solution, like a dread virus lingering dormant in the bloodstream.

We visited a Buddhist temple, filled with bottles of Mazola oil that devotees bought, offered up, then paid good money for once again on their next visit, when the bottles were moved from the altar back to the shop shelves. In a large bowl full of slips of yellow paper, the temple sold I Ching quatrains — a bit like the messages found in fortune cookies. Mine held a verse promising money, success, happiness, and fame. Mrs. Wren tentatively groped the pile and selected hers. “Chance of Success: POOR,” it read, adding that no matter how hard she worked, she could never go forward, but only aimlessly spin her wheels. As she read it aloud, she sighed in a way that scared me.

Next, we stopped in at a souvenir shop, where she insisted on buying me a little elephant statue as a good-luck charm. When she hesitated a dozen times, agonizing about whether to choose the mock-ivory white plastic or the imitation jade, she frightened me. I’d seldom seen such everyday displays of neurosis. The shop owner looked at her as if she were insane, fretting over such a cheap curio. But I was moved by the gift, remembering a detail in her poem. She’d bought her husband an elephant trinket to try to dissuade him from suicide.

That evening, I took Mrs. Wren to see the film version of a classic British novel. She then stayed up half the night, pacing from the kitchen to the bathroom and back to the living room sofa bed. (She insisted on sleeping there instead of taking my room, an invitation she refused.) Once I came out to ask her if anything was wrong. She was as restless as a tortured moth hovering near a lamp. I found her engrossed in reading The Sex Atlas, the one volume she had pulled from my bookshelves. She stealthily put it back.

The next morning, we had brunch at a coffee shop. After a long tug-of-war with her, I insisted on paying. Browsing in a bookstore, she grew so exhausted that she tried to sit on a display of books. The security guard came over and told her to keep moving, as if she were a bag lady.

Mrs. Wren spoke with determination about wanting to serve the sick and dying, and she asked to visit the homeless shelter where I did a little volunteer work. But she had no energy left, and I couldn’t bear to see her limp. We took a cab to Port Authority. She gazed out the window en route, commenting: “The sun has come out — a nice gesture!” We sat waiting for her bus, surrounded by the homeless mentally ill, transvestite prostitutes, and others caught in the flotsam and jetsam of New York life in those days. Against one wall of the bus station sat an elderly woman with a shaved head, accompanied by a pet rabbit. A sign explaining her predicament said that she’d undergone brain surgery and then been unlawfully evicted, after the landlord tried to poison her rabbit.

This apparition apparently triggered another in Mrs. Wren’s inexhaustible supply of memories. It featured a neighbor’s son, beaten so savagely during the Cultural Revolution that he became mentally defective and would wander away from home for days at a time.

During one October 1st National Day celebration, she recounted, the boy managed to ride a train all the way to Beijing. There he was seized by police and while being returned to Shanghai in custody, he somehow lost his life. It took the neighbor’s family years of investigating to establish the cause of death: a police beating for which no amends would be made. It took them more years of searching to find and pay respects to his ashes.

As she talked about this injustice, I resolved to remember her next birthday with a string of pearls, to replace the ones confiscated by the Red Guards. She got on the bus that day, and I haven’t seen her since. Sometimes I like to think that the visit did her some good. But if she really allowed such interactions to touch and heal her, how could she live without more of them?

With an exaggerated sense of Chinese propriety, she refuses to come back to my place until she can reciprocate my first invitation, which she can’t afford to do. I tried to cut through the thicket of expectations by making the trip out of town and simply showing up at her apartment. She wasn’t home, or at least she didn’t answer the door. When the Bard professor later told me how much my unannounced visit disturbed her, I realized that I’d better not try it again.

In the months that followed, I kept in touch by mail, then waited weeks for each overture to be acknowledged. Every time I hear from her, it strikes me that she somehow tries to will me to forget her until she’s ready to be remembered again.

Mrs. Wren says she started doing volunteer work in hospitals because the only people she feels comfortable with are the sick, the helpless, and those with nowhere to go. She especially likes to care for the dying: “those who will soon cross over to the other side of the river.”

“It’s a terrible smell, impersonal but spiritually uplifting,” she says, adding: “I would not like to be the last one left alive.”

I sent her pearls for her birthday and made it a point to get the nicest ones I could afford. The gift upset her because, in keeping with traditional Chinese etiquette, she feels obliged to respond with a precisely tantamount present. The tone of her thank-you note was stern, almost denunciatory. “You must promise me never to do this again,” she wrote as if I’d wronged her.

A Chinese Eleanor Rigby (The Shanghai Friendship Store — Chapter 1, Part 1)

The Shanghai Friendship Store © 2019 Susan Ruel, all rights reserved

About the author

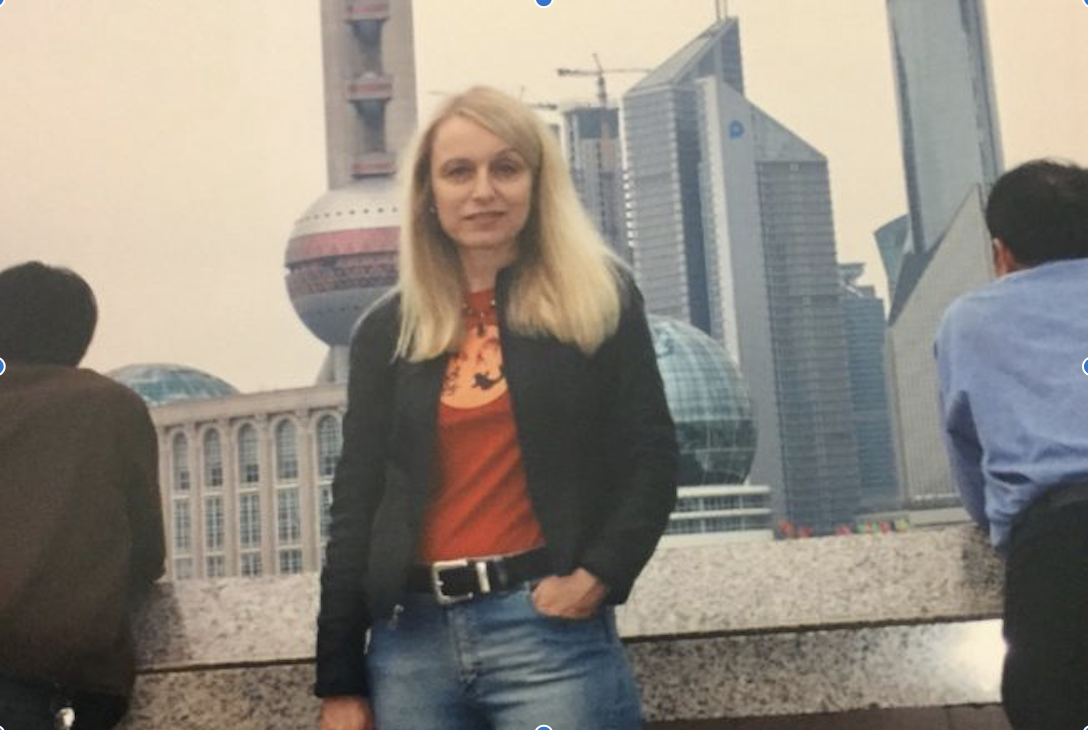

Susan Ruel “has worked on the international desks of the Associated Press and United Press International and reported for UPI from Shanghai, San Francisco, and Washington. A former journalism professor, she co-authored two French books on U.S. media history. A Fulbright scholar in West Africa, she has served as an editorial consultant for the United Nations in New York and Nigeria. Since 2005, she has been writing and editing for healthcare non-profits in New York.”

Important Note: The work appearing herein is protected under copyright laws and reproduction of the text, in any form, for distribution is strictly prohibited. The right to reproduce or transfer the work via any medium must be secured through the copyright owner.

Follow us on Twitter, Facebook, or Pinterest