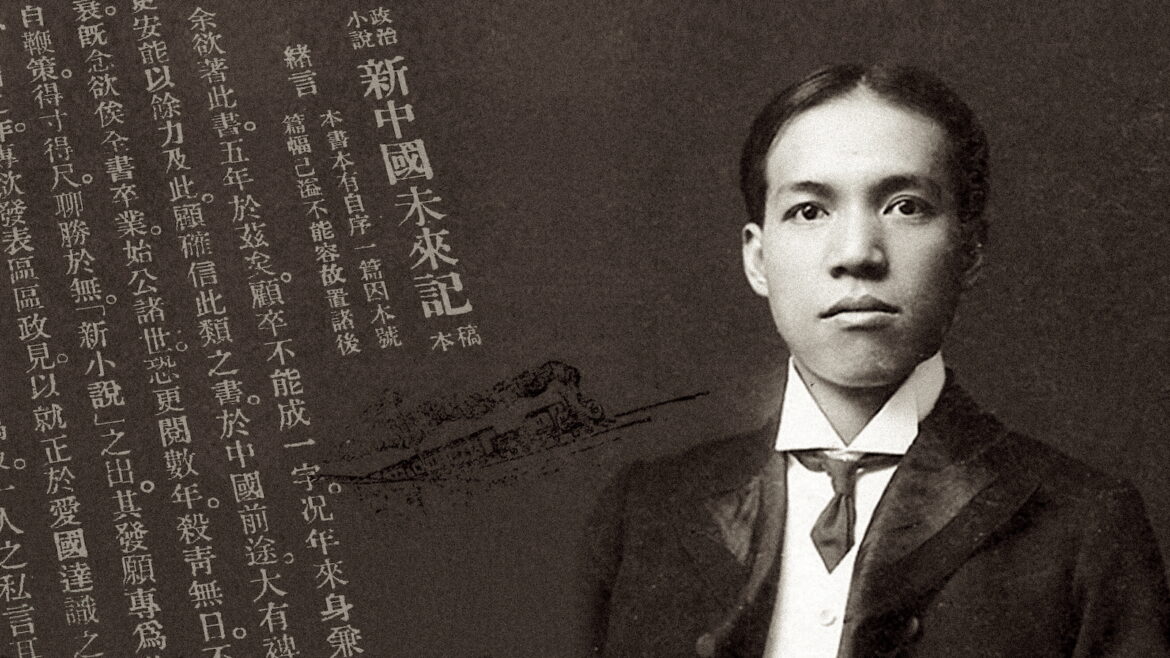

In modern Chinese history, Liang Qichao stands as a towering figure of thought. He was the trailblazer of reform, the mentor of the New Culture Movement, and the spark that stirred a nation’s awakening. Yet few know that in his final years, this great mind — once a fierce champion of reason and science, who had denounced Buddhism as mere superstition — left behind a confession that startled all who heard it.

The arrogance of youth

In his younger days, Liang Qichao burned with the zeal to overthrow “ignorance and backwardness.” He proclaimed in speeches and writings: “Cause and effect, reincarnation — all are absurd myths! It is because the people cling to religion that China cannot be renewed.” He even denounced Buddhism as “a chronic disease of the nation,” likening it to opium — a poison that crippled both body and spirit. Such words won him the admiration of young intellectuals, and Liang Qichao soon became a beacon of the new age.

Yet in one lecture hall, seated quietly in the corner, was a gray-robed monk with palms pressed together — the future Buddhist master, Venerable Xuyun. He whispered: “Cause and effect are no superstition — time will reveal their truth.” However, Liang Qichao dismissed him with scorn.

A mother’s warning

Liang Qichao’s mother, a devout Buddhist, often pleaded with him: “Qichao, disbelief is one thing, but never slander the Dharma. Words of contempt sow karma, and karma will return.” He laughed: “Mother, if cause and effect were real, why do the wicked live in wealth and ease?” She sighed: “Cause and effect span three lifetimes; retribution simply has not yet come.”

Signs and shadows

From 1915 on, Liang Qichao was haunted by dreams — dark halls, and a heavy voice accusing him: “Liang Qichao, you slandered the Dharma; your burden is great.” At first, he thought it was just a delusion caused by exhaustion. However, the same dream kept recurring with increasing clarity. During lectures, he felt as though monks at the back were watching him, their eyes gazing at him with sorrow. Doctors found no illness. But the shadows grew. Doubt entered his heart.

The blow of life and death

In 1918, his mother passed, tearfully warning him with her final breath: “My son, you are extremely talented yet overly arrogant. Remember, heaven sees all. Stop defaming Dharma.” Though nodding his head, he did not truly take it to heart. Two years later, tragedy struck — his second son died young. The devastating blow of the elderly burying their young nearly shattered his armor of reason. At the funeral, Master Xuyun appeared again: “The child’s short life has its karmic reasons. Karma and retribution are real. Be cautious in word and deed.” Liang Qichao forced a laugh, but unease gnawed at him.

Awakening on the sickbed

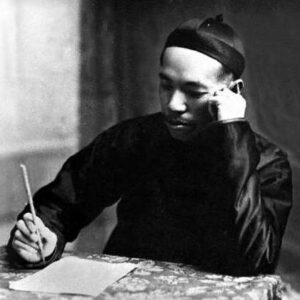

In 1923, he was hospitalized for a diseased kidney, but the doctor mistakenly removed the healthy one instead. The failed surgery worsened his illness. Alone in his ward, he opened the Buddhist scripture once given by Xuyun. The words pierced him: “To slander the Dharma is to fall into the deepest hell.” He trembled. Had he, with his eloquence, misled countless souls away from the refuge of faith? A few years later, in a Tsinghua lecture, he broke down before his students: “I was wrong — wrong for twenty years! Cause and effect are real. Buddhism is not superstition but the law of the universe. My words in the past have misled many. I wish to spend my remaining life in repentance.” The hall fell silent

“Today, I want to confess before you. I have slandered Buddhism for twenty years. Only recently, after a personal experience, did I fully understand the truth of karma and retribution.” His voice shook as he told of his visions: “It was late at night… as I was writing, suddenly, there was the sound of a heavy temple bell outside of my window. I saw a shadowy figure, a monk in a tattered robe with a hunched back, his eyes piercing my heart like burning torches. I froze, and an icy chill rushed through my spine into my skull. Silently, the monk raised his hand and pointed behind me.”

“I turned around and appeared on the wall were my published articles on defaming the Dharma over the years. Each word was clearly floating in midair, like ironclad evidence carved into the void. Just then, the monk spoke: ‘Are you aware how each word misleads people? Do you know the sin of slandering the Dharma is greater than killing one’s parents?'”

“The scenery changed at that moment. I seemed to have fallen into a fiery abyss, where blazing flames burned the sky, and countless figures struggled. Their souls were in severe torment, having no one to save them, their bodies branded with the words from my writings. These souls were none other than those who had lost their faith in the divine because they believed in my speeches and writings. The monk pointed at me and said coldly: ‘Unless you repent, this will be where you end up.’” The students wept in silence. At this moment, their former passionate mentor had transformed into a sincerely repentant soul.

A life turned back

Thereafter, Liang Qichao withdrew to temples, worshiping Buddha, chanting mantras, reading scriptures, and whispering prayers every night in the candlelight. He often copies the Ksitigarbha Sutra, reading and weeping: “If in future ages, others blaspheme the Dharma, may I bear their burden.” He realized: Science unveils the world of matter; the Dharma illuminates the world of mind. The two need not oppose; together they form true awakening.

The final rest

In 1927, gravely ill, Liang Qichao saw Xuyun once more. The master said gently: “To turn back is great courage. With sincere repentance, karma too can be transformed.” Liang Qichao replied in tears: “May the merit of my life be dedicated to all beings.” Not long after, he passed away peacefully — hands folded, a faint smile upon his lips. On his bedside lay the worn scripture. Its cover, nearly rubbed away, still bore the characters of “Repentance.”

Translated by Katy Liu and edited by Tatiana Denning

Follow us on X, Facebook, or Pinterest