This is the story of a female Chinese official, Luo Yaping, who was dubbed the “Three Most” by anti-corruption investigators. The “Three Most” refer to: the Lowest Rank, the Largest Amount, and the Worst Means.

Luo Yaping is said to have had the “lowest rank” because she was only a section-level cadre. She is said to have had the “largest amount” because the amount involved in her case was so high from embezzlement, bribery, and unexplained sources. She is said to have the “worst means” because she dared to be shady, domineering, and evil.

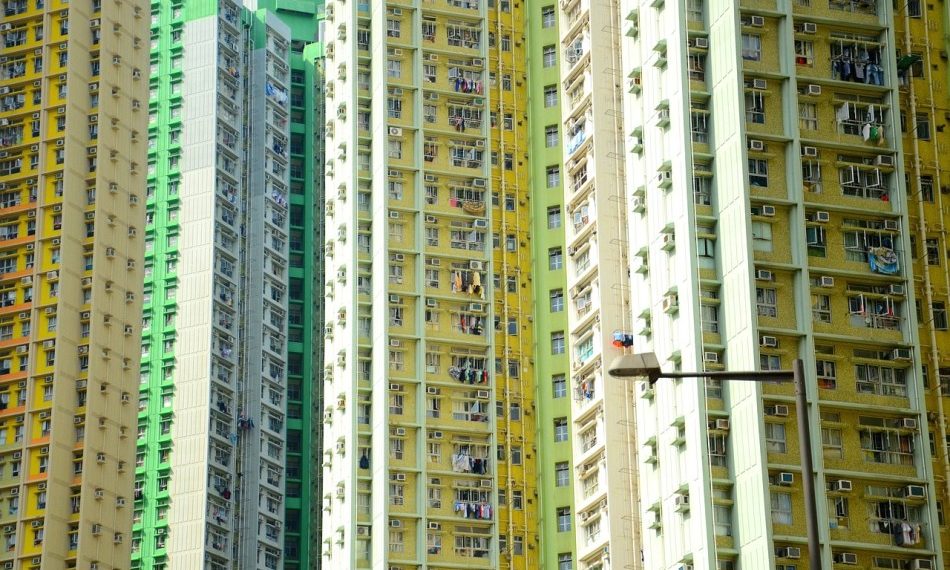

Luo’s case defined the low-level, high-impact corruption in land transactions. This was a trend in China during the massive urbanization boom (approx. 2000-2015). The verdict in Luo Yaping’s case cites nearly 35 million yuan in embezzlement/fraud and 32.55 million yuan from “unknown origin,” and led to her execution, becoming a visible public example of corruption in China’s rapidly developing land sector.

The domineering “Land Grandma”

Born to ordinary cadres, Luo failed to gain admission to college. After starting work as a correspondent at age 18, she later found herself at the Land and Resources Bureau. In 1997, when large-scale development began, land became a highly valuable commodity.

Luo Yaping became a section-level cadre of the Land and Resources Bureau in Fushun, Liaoning Province, earning the notorious nickname “Land Grandma.” This title stemmed from the absolute power she wielded over local land acquisition, demolition, and approvals.

Though a lowly clerk, she held the crucial “right to preliminary review of land approval.” Anyone seeking permission had to “look at her face.” If a “gratitude” payment was offered, procedures were cleared in seconds. If not, she would demand: “No money, no way!” She acted as a “queen” of the land world, deciding the fate of property and compensation, using her bureaucratic authority to delay or obstruct non-compliant developers and residents.

A tyrant in the property boom

Luo Yaping was infamous in Fushun for her aggression, acting “more like a street thug than a government official.” She dealt with residents facing eviction with intense cruelty. Staff members recalled Luo Yaping transforming into a “rural shrew,” hurling curses that “crushed the entire crowd.” Her brutal tactics meant most demolition households resigned themselves to receiving no additional compensation.

Her arrogance reached absurd heights. In May 2006, after a district government meeting, she rushed into the government compound and shouted, “I got the money to support you! Without me, you would be starving!” Her brazenness was only tolerated because so many officials were complicit in her schemes.

Ruthlessness and the protective umbrella

Luo Yaping’s cruelty was exemplified by her betrayal of her old, frail middle school teacher, to whom she allocated only one unit of resettlement housing before personally pocketing the proceeds from the second unit. Her middle school teacher was old, frail, blind, and living in poverty. In 2005, the teacher’s 120-square-meter house was scheduled for demolition. He wanted to change to two 60-square-meter relocated houses, one for his residence and one to rent out to supplement his living expenses.

Hearing that Luo Yaping was in charge of this matter, the old man on crutches, trembling and being helped by others, came to visit her. Luo Yaping patted her chest and said, “Teacher, don’t worry, I’ll take care of this little thing for you!” The result? The old man was allocated only one unit of resettlement housing. When he went to Luo Yaping again, Luo said coldly, “Don’t you think you can afford it? That unit is gone!” The truth was, she never planned to give the old man the second property..

The reason Luo Yaping dared to be so unscrupulous was her powerful “protective umbrella” — a network of bribed officials. Her most critical ally was Jiang Runli, the Deputy Secretary General of the Fushun City Committee and former Director of the Urban Construction Bureau, a woman as strong as she was.

Luo’s money ensured she had immunity not just over her department but from the entire municipal leadership, who were paid off or intimidated, illustrating the corruption of the “personnel track.” Luo Yaping showered Jiang with luxury goods, including gold and silver jewelry, 48 Rolex watches, 253 Louis Vuitton designer bags, more than 1,200 sets of designer clothes, and shopping cards worth hundreds of thousands of yuan. Jiang Runli accepted over 4.7 million yuan in bribes from Luo, in exchange for her silence and protection. This extravagance earned Jiang the nickname “LV Queen” and was later sentenced to life in prison.

The Land Management Center: A cash cow with no oversight

In 2002, Luo Yaping took on the concurrent role of Director of the Land Management Center. This created a critical systemic loophole: the center handled land transaction funds that were excluded from national finance, effectively creating a cash-rich zone with virtually no central supervision.

Luo exploited this flaw, often instructing developers to write checks to her personally. The Supreme People’s Court confirmed that she embezzled 32.39 million yuan in public land compensation between 2004 and 2007, according to Xinhua News. At the time of her case, she held 22 upmarket properties and fraudulently used the names and ID of 12 people to reap over 10 million yuan in compensation.

Her fall and execution

Sensing the shifting political climate following the investigation of higher-ranking Fushun officials in 2005, Luo Yaping attempted to flee. She paid US$200,000 to arrange a sham marriage with a Chinese Canadian to apply for immigration. In July 2007, the Liaoning Provincial “7.09” special task force was established, and Luo Yaping was placed under investigation.

While being placed under “isolation and investigation” by the Discipline Inspection Commission, Luo Yaping remained arrogant. She shouted at the investigators. “Call your secretary! If he doesn’t come, I’ll go on a hunger strike!” When the deputy secretary of the Discipline Inspection Commission arrived, she made a direct offer: “Release me, and I’ll give you 6 million!”

In December 2010, Luo Yaping was sentenced to death by the Shenyang Intermediate Court for embezzlement, bribery, and possessing 32.55 million yuan in assets from an unknown origin. Luo Yaping appealed the verdict, but the Liaoning High Court upheld it in June 2011. In November of the same year, the Supreme Court approved her execution by lethal injection in Shenyang at the age of 51.

The Supreme People’s Court upheld the sentence, ratifying the final verdict, underscoring the central government’s severity in punishing both corruption and abuse of power. Luo Yaping was executed by lethal injection in November 2011. Her body was buried in a cemetery in Shenyang, her final resting place.

Conclusion: The tragedy of systemic loopholes

Luo Yaping’s story remains a classic example of “small officials with huge greed.” Her execution was a public example to address rampant public anger over land disputes and forced evictions during a significant period of urbanization, which were a major source of social instability at the time. The execution of a section-level official for financial crimes is relatively rare in China compared to senior “tigers.”

Her execution by lethal injection in November 2011, a decision ratified by the Supreme People’s Court, highlights how seriously the central government viewed her specific combination of brutality (as the “Land Grandma”) and massive financial fraud, especially given the social impact of land corruption.

Her tragedy underscores critical flaws in the system: the unchecked authority of low-level cadres over high-value land approvals, the exclusion of local financial centers from national oversight, and the widespread existence of a “protective umbrella” dynamic in which money flows upward to purchase immunity from high-ranking officials.

Translated by Chua BC and edited by Helen London

Follow us on X, Facebook, or Pinterest