The saying “wealth does not last beyond three generations” is a popular proverb in China. It means that the first generation works hard to accumulate wealth; the second inherits the family business and enjoys the fruits of that labor without practicing thrift or humility; and by the third generation, born into privilege, people often take pleasure as their life’s goal. Without the restraint of family traditions or moral guidance, they lack proper values.

Such individuals often fail to manage wealth and resources wisely, becoming lost in greed and extravagance, which eventually leads to the family’s decline. Although this saying is more a social observation than an absolute rule, it reflects how families understand the relationship between virtue and wealth and how this relationship shapes their destiny.

In traditional Chinese culture, “blessings and virtue” are considered invisible wealth that can be inherited within a family. This wealth is invisible because it cannot be forcibly taken away. Ancient culture is filled with sayings and stories such as, “Those who accumulate great virtue will surely have descendants to carry it on,” and “A family that accumulates virtue will enjoy lasting blessings.”

When virtue is preserved

A famous example is General Guo Ziyi of the Tang Dynasty. Despite his high rank and extraordinary achievements, he remained humble and respectful, treating scholars with courtesy and helping members of his clan regardless of their status. The Old Book of Tang records: “Guo Ziyi, though at the highest rank, was as modest as a commoner, treating scholars with respect and his clan with kindness.” Even after his death, his descendants survived political upheavals unharmed. History notes: “Since the rise of the Tang, no minister was as great as Guo Ziyi, and yet all his descendants were preserved.” This shows that family prosperity depends on the inheritance of virtue, not merely on power or wealth.

In the Qing Dynasty, Lin Zexu was appointed Imperial Commissioner to Guangzhou to ban opium. Many attempted to bribe him, offering millions of taels of silver, but he refused, determined to eradicate opium for the sake of the people. He destroyed nearly 20,000 chests of opium at Humen. The following year, under British military pressure, the Qing court dismissed and exiled him for five years. After his death, although his family possessed little wealth, they did not decline. For generations, his descendants continued to excel in learning, with some becoming scholars and officials. Even during the Republican era, his family remained distinguished. One descendant, Lin Xiang, served as Chief Justice of the Supreme Court and was also known for his high moral character.

Zeng Guofan, also of the Qing Dynasty, commanded the Xiang Army and wielded immense power. Yet, he never took a single penny from military funds for his family, nor did he profit from salt revenues. Concerned that his descendants might become corrupted by luxury, he deliberately left them no material wealth. Instead, he emphasized discipline, learning, and self-cultivation. As a result, his family continued to progress and produced many capable individuals. Statistics show that in nearly 200 years since Zeng Guofan, spanning eight generations, there has not been a single “prodigal son.” Almost 200 of his descendants received higher education, and more than 240 became distinguished figures.

By contrast, wealthy merchant families such as the Wu, Pan, and Kong clans in Guangdong amassed enormous fortunes during the Opium War and lived in extreme extravagance. Yet within only a few decades, none of their descendants achieved notable success, and all of these families eventually declined.

In the early 1990s, during China’s reform and opening-up period, a wave of entrepreneurs moved south in search of opportunity. A young man from Beijing, nicknamed Xiao Han, went to Guangzhou to start a business. With intelligence, keen business instincts, and his friendly Beijing accent, he earned one million yuan in just three years — an astonishing sum at the time. He purchased a luxury Lexus and drove it back to his hometown, instantly becoming the focus of attention. Years later, at a reunion, when people praised his business achievements, he smiled and spoke of his grandfather, a landlord who had been persecuted and killed during the land reform. His family, he explained, had always been hardworking, kind, and charitable, often helping the poor during times of famine — virtues that had earned them respect and, in time, prosperity.

When wealth is taken

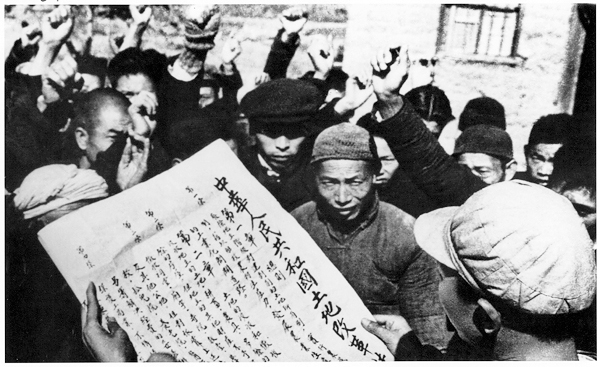

In 1950, just three months after seizing power, the Communist Party launched nationwide land reform under the slogan “land to the tiller.” It incited poor peasants to struggle against landowners, encouraged violence, and openly called for the elimination of the landlord class. Millions were labeled “landlords,” “rich peasants,” “counterrevolutionaries,” or “bad elements,” turning them into targets of discrimination, persecution, and even mass killing. Nearly 100,000 landlords were killed, and in some regions, entire families were exterminated, including women and children. Homes were destroyed, property confiscated, and even stored food was seized. Some kind-hearted peasants, unable to bear the injustice, secretly returned stolen grain under the cover of night. Xiao Han’s father barely survived those terrifying years.

Xiao Han later observed that the peasants who had seized his family’s property remained poor, with many of their descendants dependent on government aid. Meanwhile, the descendants of the landlords persecuted alongside his grandfather went on to live in prosperity, raising thriving families and enjoying stable, contented lives.

In ancient times, noble families were defined not by their possessions, but by the virtue they inherited — by character, discipline, and moral depth passed down through generations. Today, many abandon virtue, the true determinant of destiny, and pursue only material wealth, forgetting that without moral foundations, wealth itself cannot endure.

History repeatedly shows that wealth gained without virtue cannot endure, while families grounded in moral character continue to prosper across generations. Power may rise and fall, property may be seized or squandered, but virtue cannot be taken by force. It is this invisible inheritance — passed quietly from one generation to the next — that determines whether a family rises, survives, or declines. Those who understand this truth do not ask how to accumulate wealth, but how to preserve character, knowing that only virtue allows prosperity to last.

Translated by Cecilia and edited by Tatiana Denning

Follow us on X, Facebook, or Pinterest