On the morning of April 16, 1951, General Douglas MacArthur prepared to leave Japan for the last time. President Truman had just relieved him of command, ending his role as Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers.

What happened next stunned observers worldwide. As MacArthur’s motorcade made its way from the U.S. Embassy to Haneda Airport, over 200,000 Japanese citizens lined the streets of Tokyo. They had gathered spontaneously in the early morning hours to say farewell to the American general who had occupied their country for nearly six years.

At the airport, Emperor Hirohito himself arrived to bid goodbye. With tears in his eyes, MacArthur clasped the hands of the man he had chosen to spare from war crimes prosecution. Prime Minister Shigeru Yoshida spoke for many Japanese when he declared: “General MacArthur, you have saved us from the fear of panic, uneasiness, and chaos by leading us down the path of post-war reconstruction and recovery. You have spread the seeds of democracy in every corner of our country.”

How did an occupying military commander earn such genuine affection from a conquered people? The answer lies in one of history’s most remarkable transformations, a story of pragmatic idealism, bold reform, and the power of treating former enemies with dignity.

The state of Japan at war’s end

When MacArthur arrived in Japan on August 30, 1945, the nation lay in ruins. American bombing had destroyed 40 percent of urban areas. The economy had collapsed. Disease spread through the population. Millions faced starvation.

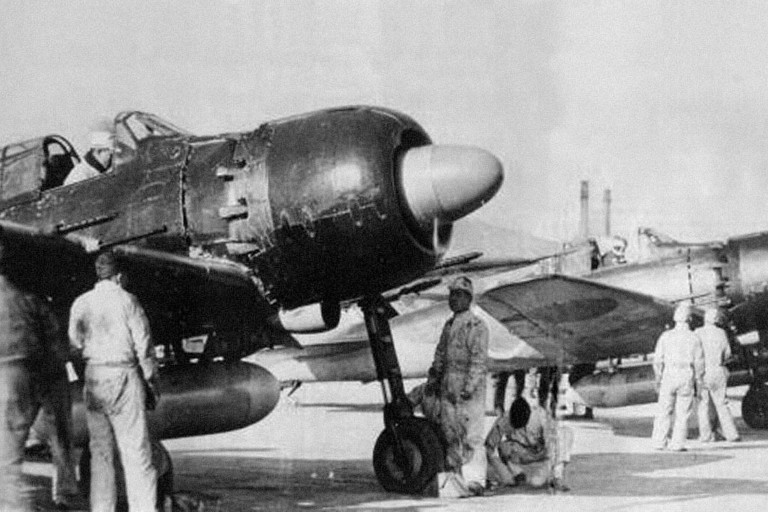

Japanese soldiers lined MacArthur’s route from Atsugi Airfield with fixed bayonets turned outward, a gesture of protection that also revealed the fear many harbored about what occupation would bring. Memories of Japanese military behavior in conquered territories gave people reason to expect the worst.

MacArthur arrived without ceremony or grand parade. He wore no sidearm. This deliberate choice signaled his intention to rebuild rather than punish, to lead rather than dominate. Over the following six years, he would fundamentally transform Japanese society through a combination of immediate humanitarian action, sweeping institutional reform, and respectful engagement with Japanese culture and leadership.

Three phases of the occupation (1945-1952)

According to the U.S. State Department, the occupation of Japan proceeded through three distinct phases, each responding to changing circumstances and priorities.

Phase one: Reform and reconstruction (1945-1947)

The initial phase focused on demilitarization and democratic reform. MacArthur moved quickly on multiple fronts.

Humanitarian response: Recognizing that hungry people cannot build democracy, MacArthur pressured Washington for immediate assistance. The result was 3.5 million tons of food and US$2 billion in emergency aid that prevented mass starvation and earned Japanese trust.

War crimes accountability: The Tokyo Trials prosecuted major war criminals while MacArthur made the controversial decision to shield Emperor Hirohito from prosecution. He calculated that preserving the emperor as a constitutional figurehead would provide stability and legitimacy for reforms.

Political transformation: MacArthur disbanded the Japanese military, purged militarists from government, released political prisoners, and lifted censorship. He created conditions for democratic participation where none had existed.

Phase two: The reverse course (1947-1950)

By late 1947, the emergence of the Cold War forced a reconsideration of occupation priorities. The PBS American Experience documents how this period saw a shift from punishment to partnership.

With communist victories in China and tensions rising in Korea, American strategists recognized Japan’s potential as an ally rather than a reformed enemy. Economic recovery became paramount. Some earlier reforms were relaxed as the United States sought to strengthen Japan against communist expansion.

Ironically, it was now Americans pressing for Japanese rearmament while Japanese leaders resisted in the name of the American-written constitution. The occupation’s own success had created new complications.

Phase three: Peace and alliance (1950-1952)

The final phase concluded with the 1951 San Francisco Peace Treaty, which formally ended the state of war and restored Japanese sovereignty. A separate security treaty established the U.S.-Japan alliance that continues today.

By the time MacArthur departed, the groundwork for Japan’s remarkable postwar success had been laid. Within a decade, Japan would become the world’s second-largest economy.

Revolutionary reforms under MacArthur

The scope of MacArthur’s reforms touched nearly every aspect of Japanese society. Understanding these changes reveals how thoroughly the occupation reshaped the nation.

Political reforms and the emperor question

MacArthur faced an immediate dilemma: what to do with Emperor Hirohito? Many Americans and Allied leaders wanted him tried as a war criminal. MacArthur disagreed.

He recognized that the emperor served as the living symbol of Japanese national identity. Putting Hirohito on trial would have created a martyr and complicated every subsequent reform. Instead, MacArthur had the emperor publicly renounce his divine status while retaining his position as a constitutional figurehead.

This pragmatic decision proved crucial. The emperor’s endorsement gave legitimacy to reforms that might otherwise have faced fierce resistance.

The new Japanese constitution

Perhaps no single achievement better demonstrates MacArthur’s impact than the Japanese Constitution of 1947, also known as the “MacArthur Constitution.” When Japanese officials submitted a conservative draft that merely revised the old Meiji Constitution, MacArthur rejected it outright.

On February 4, 1946, he ordered his Government Section to draft an entirely new document. Staff member Beate Sirota Gordon, then in her early twenties, recalled being told the team would “write the Japanese constitution” in one week.

Working from three basic principles MacArthur had written himself, the team produced a revolutionary document. It transformed the emperor from a sovereign ruler to a symbolic figurehead. It established a parliamentary democracy with robust protections for individual rights. It granted women the right to vote and hold office. It protected labor unions and collective bargaining.

Most remarkably, it included Article 9, the “no-war” clause.

Economic reforms

MacArthur attacked the economic structures that had supported Japanese militarism. He attempted to break up the zaibatsu, the massive industrial conglomerates that had powered the war machine. Land reform transferred ownership from wealthy landlords to tenant farmers, creating a rural middle class with a stake in the new democratic order.

These reforms had mixed results. The zaibatsu dissolution was never fully completed, and some conglomerates eventually reconstituted themselves. But the land reform succeeded dramatically, transforming rural Japan and building support for democracy among millions of farmers.

Social reforms

Beyond politics and economics, MacArthur encouraged changes in daily Japanese life. Women gained legal equality, including the right to vote, own property, and seek divorce. Labor unions received protection and the right to organize. Education was decentralized, with locally elected school boards replacing centralized control.

MacArthur even attempted, unsuccessfully, to promote Christianity in Japan. While this effort failed, it illustrated his belief that transformation required changing hearts as well as institutions.

Article 9: Japan’s no-war clause

Article 9 stands as one of the most unusual provisions in any national constitution. It states:

“Aspiring sincerely to an international peace based on justice and order, the Japanese people forever renounce war as a sovereign right of the nation and the threat or use of force as means of settling international disputes. Land, sea, and air forces, as well as other war potential, will never be maintained.”

The origins of this clause remain disputed. MacArthur claimed that Prime Minister Shidehara suggested it during a private meeting on January 24, 1946. Others attribute it entirely to MacArthur’s initiative. According to the Council on Foreign Relations, the truth may involve both men recognizing the strategic value of such a declaration.

For Japan, Article 9 offered protection against future military entanglements. For the United States, it ensured that a rebuilt Japan could never again threaten American interests. The clause became central to Japanese national identity, though its interpretation has been debated ever since.

MacArthur’s leadership approach

What made MacArthur effective where other occupiers have failed? Several factors stand out.

Respect for Japanese culture: Despite his authority to rule by decree, MacArthur worked through Japanese institutions whenever possible. He retained the emperor, preserved the bureaucracy, and used Japanese officials to implement reforms. This approach gave Japanese people ownership of changes rather than imposing them as foreign demands.

Swift humanitarian action: By addressing hunger and disease immediately, MacArthur demonstrated that the occupation served Japanese interests, not just American ones. This built trust, enabling more controversial reforms.

Clear vision with flexible implementation: MacArthur knew what he wanted to achieve but remained pragmatic about methods. When initial approaches failed, he adjusted rather than persisting in futile efforts.

Personal presence and accessibility: MacArthur lived in Japan throughout the occupation, visible to ordinary Japanese in ways that previous rulers had never been. His willingness to engage with Japanese society, even as he transformed it, earned respect.

Like Emperor Taizong of Tang, who built China’s golden age by accepting criticism and governing with benevolence, MacArthur understood that lasting transformation requires winning hearts, not just battles.

The legacy that shaped modern Japan

The occupation officially ended in 1952, but its effects endure to this day. Japan has maintained democratic governance for over seven decades. The U.S.-Japan alliance remains a cornerstone of Pacific security. Article 9, though reinterpreted over time, still shapes Japanese defense policy.

Most remarkably, Japan achieved what seemed impossible in 1945: transformation from a militaristic empire that had attacked its neighbors into a peaceful, prosperous democracy respected worldwide. Within fifteen years of surrender, Japan had become an economic powerhouse. By the 1960s, it was the world’s third-largest economy.

This success had many causes beyond MacArthur’s occupation: Japanese cultural values of education and hard work, favorable Cold War economics, and talented Japanese leaders who built on the occupation’s foundation. But the framework MacArthur established made the transformation possible.

Lessons from MacArthur’s occupation

The Japanese occupation offers insights relevant far beyond its historical moment.

Transformation requires investment: MacArthur understood that rebuilding a nation costs money. The humanitarian aid that prevented starvation was not charity but investment in stability.

Former enemies can become allies: The Japanese farewell to MacArthur demonstrated that occupation need not create lasting enmity. Treating a conquered people with dignity can build bonds that endure.

Institutions matter more than individuals: MacArthur’s personal authority was immense, but he focused on building institutions that would outlast him. The constitution, the democratic processes, and the economic reforms were designed to function without American supervision.

Cultural respect enables change: By working through Japanese institutions and respecting Japanese sensibilities, MacArthur achieved reforms that pure coercion could never have accomplished.

The story of MacArthur and Japan reminds us that nations can change, that former enemies can become friends, and that wise leadership can turn destruction into opportunity. Those 200,000 Japanese citizens who gathered to say farewell in 1951 understood something profound: they had witnessed not just an occupation, but a rebirth.

Translated by Yi Ming

Follow us on Twitter, Facebook, or Pinterest