The history of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is marked by the massive use of violence against the Chinese people as a means of total control. This may appear like a line from a cold war propaganda film, but it’s based on historical events, of which five of the worst atrocities committed by the CCP are outlined further below. Several of them are not widely known.

“Systematic violence and calculated terror [is] designed to instill fear and intimidation into anybody who comes into contact with the Communist Party of China,” said Frank Dikötter, chair professor of humanities at the University of Hong Kong, at a forum held at the Library of Congress in 2015.

Since taking power in 1949, the Party has committed some of the worst atrocities in the modern age. The examples below are listed in chronological order going backward, starting with the ongoing crime of forced organ harvesting to more historical events that were so catastrophic that they are difficult to grasp. In China, talking about such issues remains forbidden.

Five atrocities committed by the CCP

1. Organ harvesting: an ongoing atrocity

The industrial-scale killing of prisoners of conscience for their organs in China is a crime so awful that many initially found it too hard to believe. Since an initial 140-page report on allegations was released in 2006, this has largely changed due to the efforts of researchers, journalists, and activists, including many in the medical profession.

“There is today increasing commentary around the world about the inhuman commerce begun and run today by the party-state in Beijing. One was a 7-page cover story recently in Salud, a medical magazine read in Spain and other Spanish-speaking nations,” said former Canadian lawmaker David Kilgour at Canada’s parliament earlier this month after the screening of the award-winning documentary Human Harvest: China’s Illegal Organ Trade.

“Prisoners of conscience often convicted of nothing are the primary source of pillaged organs. They include Uyghurs, Tibetans, and Christians, but are overwhelmingly Falun Gong practitioners-long dehumanized in party-state media throughout China,” Kilgour said.

Nobel Peace prize nominee Kilgour was one of three researchers who released another report in 2016 that estimated that there are 60,000 to 100,000 organ transplants performed annually in China. Among the evidence used to calculate these figures was data from hospital revenue, transplantation volumes, bed utilization rates, surgical personnel, training programs, and state funding.

One of the other authors of the report was investigative journalist Ethan Gutmann, who also earlier published a book on the subject, The Slaughter, in 2014.

Despite the amount of money that organ harvesting can generate for those involved in the atrocity, Gutmann said that what is occurring in China is not just about money. In his opinion, it is mainly a political issue. The communist state wants to get rid of certain groups.

“I’m really interested in the victims here; these are hundreds of thousands of people. They had lives too,” he said during a Q&A session at the Foreign Correspondent Club Thailand on October 17 last year.

“These are quite real people, sometimes the best of their culture. They are incredibly brave or interesting or so forth,” he said.

Just prior to the release of the report, a U.S. House of Representatives resolution was unanimously passed that urged the Chinese government to stop harvesting the organs of prisoners of conscience, and end the persecution against Falun Gong. The European Parliament passed a similar resolution in 2013.

Falun Gong practitioners have been persecuted in China by the state since 1999, after which a sharp rise in the number of transplants in the country was seen.

Outside of forced organ harvesting, other aspects of the state’s persecution of Falun Gong practitioners have been described as severe and ongoing by researchers. The U.S-based Freedom House nonprofit recently said practitioners are at risk of arbitrary detention, torture, and extrajudicial execution.

For an extensive look at the persecution of Falun Gong, watch this China Uncensored episode:

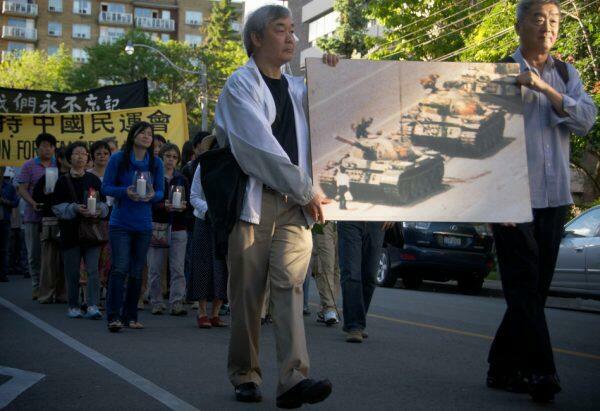

2. The 1989 crackdown: not just Tiananmen Square

The world was shocked when thousands of democracy activists, mostly students protesting in Beijing’s Tiananmen Square, were massacred by soldiers of the Peoples Liberation Army on June 4, 1989.

But it is not widely known that the killings and suppression were not limited to the nation’s capital. There were bloody crackdowns against supporters of the democracy movement in 20 Chinese cities, reported Time.

One example was what occurred in the city of Chengdu, the capital of southern Sichuan Province. In a letter written to The New York Times, Karl Hutterer, a professor of Anthropology at the University of Michigan, stated that there was a consensus that security forces killed 300-400 people in Chengdu, and many more were wounded.

“Unlike Beijing, there was little gunfire (although some people were shot); the troops used tear gas and concussion grenades to control the crowds, and attacked with truncheons, knives, and electric cattle prods. Many people were killed and more wounded,” wrote Hutterer, who was in Chengdu during the crackdown.

“The clear object of the intervention was not simply to control the demonstrators: Even after having fallen to the ground, victims continued to be beaten and were stomped on by troops; hospitals were ordered not to accept wounded students (at least in one hospital, some employees were arrested for defying the order), and on the second night of the attack, the police prevented ambulances from functioning,” he wrote.

Due to state censorship and suppression, not many Mainland Chinese today know much about the crackdown on the democracy movement, which had widespread support among the population at the time.

Part of the state’s efforts to suppress June 4 has been its callous treatment of The Tiananmen Mothers, an advocacy group, who have for years have been harassed and monitored by the police.

Despite this, they continue to speak out about the crimes committed by the state.

“A government that unscrupulously slaughters its own fellow citizens, a government that does not know how to cherish its own fellow citizens, and a government that forgets, conceals, and covers up the truth of historical suffering has no future — it is a government that is continuing to commit crimes!” wrote The Tiananmen Mothers in an open letter translated and posted by Human Rights in China last year.

For a brief overview of the Tiananmen Square crackdown, watch the following video:

3. The Cultural Revolution: A decade of madness

The Cultural Revolution began in 1966, starting with radicalized students, known as Red Guards, attacking teachers and then elements of Chinese society deemed bourgeois or anti-communist.

“We had to root out class enemies, which were categorized as the black five,” said former Red Guard Yang Nainming in an interview with Vision Times last year. Landlords, rich farmers, counter-revolutionaries, bad-influencers, and rightists made up the “black five” that communist leader Mao Zedong identified as enemies of the revolution.

The Cultural Revolution was used by Mao to get rid of perceived political enemies who opposed him after his disastrous Great Leap Forward, a campaign that resulted in the deaths of tens of millions of Chinese citizens (see further below).

“Soon, it just wasn’t children or university students — everyone in society was affected and took part in the Cultural Revolution,” Yang said.

It was so bad that family members even denounced each other for being counterrevolutionaries.

During the Cultural Revolution, the radicals also targeted the “Four Olds” — that being old habits, manners, customs, and culture. As part of this, churches, temples, and monasteries were shut down and vandalized.

Tibet and Tibetan culture also suffered greatly during the politically wrought chaos.

As state-sanctioned social chaos took hold, fighting spread across the country as pro-Mao factions fought other pro-Mao factions.

During the Cultural Revolution, there were even cases of politically motivated cannibalism. One article detailed a case that occurred in a town in the southern region of Guangxi. “The hearts, livers, and genitals of victims were cut out and fed to revelers,” said a Chinese official who asked not to be named for fear of repercussions. “All the cannibalism was due to class struggle being whipped up, and was used to express a kind of hatred,” he said. “The murder was ghastly, worse than beasts.” (Bangkok Post)

Copies of official documents smuggled out of China stated that acts of cannibalism were organized by local Communist Party officials, reported The New York Times in 1993. Those who participated in acts of cannibalism did so to prove their revolutionary spirit, said the documents.

An estimated 2 to 3 million people died in the chaos. Not long after Mao’s death in 1976, the Cultural Revolution came to an end.

Watch this FRANCE 24 English video for more on the Cultural Revolution:

4. During Mao’s secret famine, Party leaders ate well

Some 45 million people are estimated to have died in the so-called Great Famine that devastated China during the years 1958 to 1962.

The famine was brought about by the immense failure of Mao’s Great Leap Forward, which ruined the country’s economy, both its industrial and agricultural sectors.

Much like the Ukrainian famine of 1932-33, this tragedy occurred while most of the rest of the world remained largely unaware. The above figure of 45 million is an estimate put forward by the aforementioned academic Dikötter, who had access to Party archives at county and provincial levels. The Dutch historian studied hundreds of documents, and he found that like all one-party states, the Chinese communists kept meticulous records for him to base his findings on. Of that 45 million figure, he said that at least 2 to 3 million people were tortured to death or executed.

“Across the country, from archive to archive, there are abundant examples of the use of extraordinary levels of violence to get people to do things they weren’t very keen on doing,” Dikötter said when discussing his Samuel Johnson Prize-winning book Mao’s Great Famine at Harvard university in 2012.

On top of that, there were of course accounts of widespread cannibalism.

Dikötter’s work followed another English language book on the famine written by journalist Jasper Becker titled Hungry Ghosts, which was based on hundreds of interviews and years of investigations.

“Perhaps the most terrible aspect of the famine was that there was nowhere to escape from it. Even in the most remote corners of the high mountains of Tibet or in the distant oases of Xianjiang in the far west, there was no sanctuary. An exodus was impossible because the country’s borders were closed and tightly guarded,” wrote Becker in his book published in 1996.

During this time, the Party leadership always ate well, he wrote.

Mao’s policies stifled any recovery from the famine, and not until 1978 did the peasants have the same amount of food to eat as they had prior to the famine that started in 1958, wrote Becker.

5. Millions killed during the ‘Liberation’ years

Dikötter has also researched and written extensively on what occurred in China during the so-called Liberation years, when the communists began their violent reforms, among them those applied in the countryside.

“In return for a plot of land, farmers had to physically eliminate the elected leaders,” Dikötter said at the Library of Congress forum.

“Work teams of all villages from north to south were given targets of people to be denounced, humiliated, dispossessed, and murdered, with villagers assembled in the hundreds in an atmosphere of hatred. Mao made sure that with land distribution, every person in the countryside had blood on their hands,” he said.

“All of them were implicated in the murder of a small number of carefully selected targets. In other words, the pact between the poor and the Party was sealed in blood. Or to put it even differently, a sufficient quantity of blood had to be shed in order to make a return to the old order impossible. No one in these villages was allowed to stand on the side.”

Land reform killed between 1.5 million and 2 million people in the countryside between the years 1947 and 1952. As Mao began his collectivization programs, in 1954 the Party took back the land that it had redistributed to the peasants.

Again based on Party archives, Dikötter estimated that 2 million people in Chinese cities were killed during counterrevolutionary campaigns of the early 1950s.

“It is a campaign of terror that unfolds from October 1950 to October 1951. How many counter-revolutionaries are there? Very much like steel output and grain production, death comes with a quota. Mao decides that killing one per thousand in the population should be enough,” Dikötter said at the forum.

“But before you know it, of course, villages vie with villages, local cadres with other cadres, provinces with provinces, in order to eliminate as many enemies as they can. In some places, children aged six are accused of being spy leaders and tortured to death,” he said.

“Two million people are executed, often in public stadiums, in cities and the countryside alike,” he added.

So much for liberation.

Watch Dikötter’s speech in full at the forum in this video posted by Victims of Communism Memorial Foundation:

Follow us on Twitter, Facebook, or Pinterest