Lab-grown beef, also known as cultivated or cell-based meat, is no longer a science-fiction concept. It is a technological bet on whether humanity can decouple one of its most resource-intensive foods from animals, land, and methane — without losing nutrition, taste, or cultural meaning.

For most of human history, beef began as grass, passed through a ruminant stomach, and ended up on a plate. Today, a growing number of scientists believe that same steak might one day begin its life in a stainless-steel bioreactor, assembled cell by cell, without ever touching a pasture.

But before asking whether we should print beef, a more fundamental question must be asked: do we even have enough cows to feed the world at its current pace?

How beef is made today, and why scale is already strained

Globally, beef production reached approximately 76.6 million metric tons in 2023, according to FAO-aligned datasets and agricultural outlooks. Spread across the global population of more than 8.2 billion people, this amounts to roughly 6 kilograms of beef per person per year, after retail losses are accounted for. That average hides extreme disparities: beef consumption in the United States exceeds 25 kg per capita, while large regions of the world consume very little.

Behind those numbers stands a global cattle population of roughly 1.5 billion animals. Yet only a fraction of that herd is slaughtered each year — about 250 million cattle equivalents annually, depending on yield assumptions. This works because beef is a flow system, not a static stockpile.

The system works — but just barely. Beef already occupies nearly 60 percent of global agricultural land while providing less than 20 percent of the world’s calories. The FAO has repeatedly warned that rising demand in Asia and the Middle East will place additional pressure on land, feed, and emissions unless dietary patterns change or production methods evolve.

As the OECD-FAO Agricultural Outlook for 2025-2034 puts it: “With these productivity improvements and a greater share of poultry in meat production, greenhouse gas emissions are expected to rise by 6%, significantly less than the projected 13% growth in meat output over the coming decade.”

— OECD-FAO Outlook

That tension — between biological limits and rising demand — sets the stage for cultivated meat.

And once the question becomes limits, the conversation inevitably shifts from farms to factories.

What it actually means to ‘print’ beef to produce lab-grown meat

Despite the popular phrase, beef is not printed like plastic. — it is grown.

The process begins with a small biopsy taken from a living cow. Muscle stem cells and fat precursor cells are isolated and stored. These cells are then placed in a growth medium — a carefully formulated liquid containing amino acids, sugars, salts, and signaling molecules that instruct cells to divide and mature.

Inside bioreactors, cells multiply under controlled temperature, oxygen, and pH conditions. This part of the process looks less like farming and more like brewing or pharmaceutical manufacturing.

Where “printing” enters the story is in structuring. To resemble beef rather than sludge, cells must grow along scaffolds or be deposited via 3D bioprinting, forming fibers that mimic muscle tissue. Without this step, cultivated meat is functionally ground beef.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration describes cultivated meat as: “Food produced from cultured animal cells rather than from harvested animals.”

— FDA

This is not speculative science. Singapore approved the first cultivated meat product for sale in 2020. The United States followed with joint FDA-USDA approvals in 2023.

The question is no longer whether meat can be grown in a lab — but whether it can be grown cheaply, cleanly, and at scale.

That leads directly to the most emotionally charged issue of all: nutrition.

Is cultivated beef actually as nutritious as beef from a cow?

From a biological standpoint, muscle cells grown in a lab are still muscle cells. In theory, cultivated beef can match conventional beef in protein content and amino-acid profile.

However, multiple scientific reviews emphasize an important caveat: nutritional equivalence depends on design choices, not inevitability.

A 2024 review in Frontiers in Nutrition notes:

“…participants frequently mentioned concerns about CM’s (Cultured Meat’s) health impacts, nutrition quality, or food safety (…) and, often, the sensory properties of CM (…), indicating that consumers echoed some of the concerns about whether CM will be a universally positive replacement for conventional meat products.”

Certain nutrients — such as vitamin B12 and heme iron — are not guaranteed unless specifically engineered or supplemented. In conventional beef, these arise indirectly through microbial ecosystems and complex animal metabolism. In cultivated meat, they must be added intentionally.

In other words, cultivated beef is not automatically inferior — but it is not automatically identical either.

This raises a subtle but profound implication: Meat may become a designed food, optimized for fat profiles or nutrient density rather than inherited from biology.

And once nutrition becomes programmable, the conversation naturally turns to energy and cost.

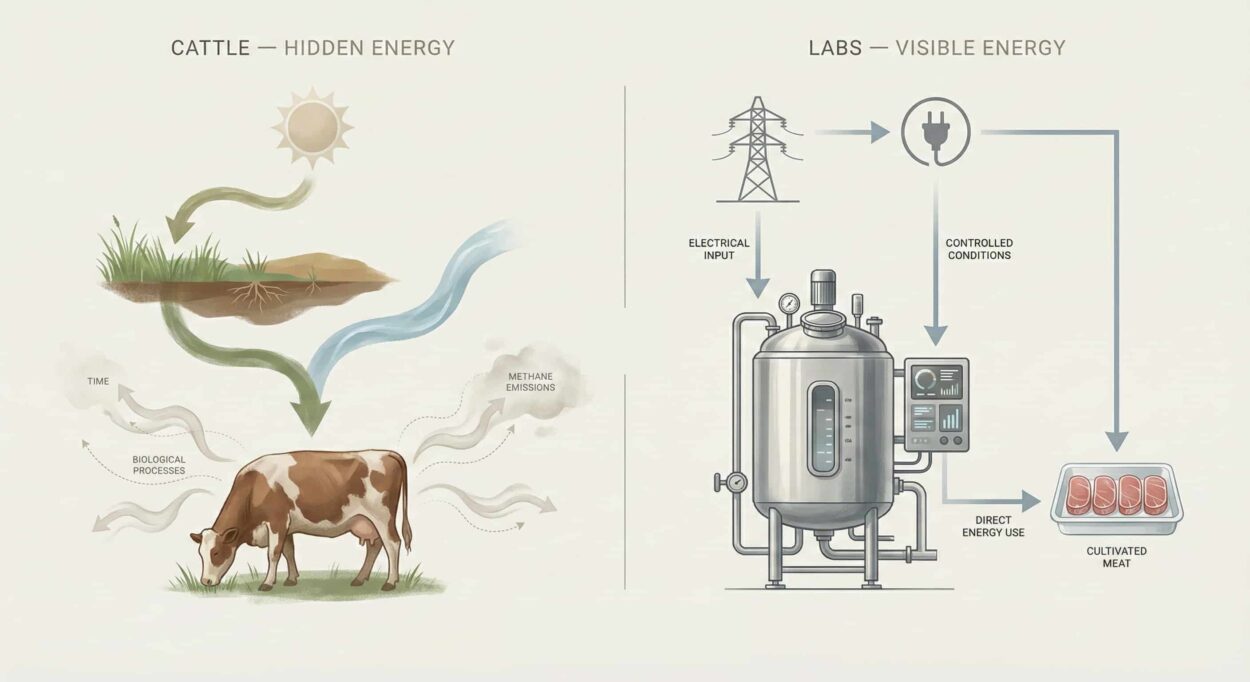

The hidden energy of cattle versus the visible energy of labs

Traditional beef production is energy-intensive, but much of that energy is biological — sunlight converted into grass, grass into muscle, time into mass. Its environmental costs show up as land use, methane emissions, and water demand.

Cultivated meat flips the equation. The energy burden becomes industrial and electrical.

A 2024 life-cycle analysis published in Environmental Science & Technology issued a cautionary finding:

If growth media are highly refined and energy remains fossil-based, cultivated meat could exceed the global warming potential of retail beef.

Earlier modeling studies, by contrast, show that under future assumptions — cheap renewable energy, food-grade growth media, and high cell density — cultivated meat could dramatically reduce land use and methane emissions.

The key insight is this: cultivated meat is not inherently sustainable. It inherits the sustainability of the energy and industrial systems that support it.

And sustainability alone does not make a product viable. Economics decides scale.

What does beef actually cost, and can labs compete?

Conventional beef pricing hides complexity. In the U.S., cattle prices in 2024 averaged around $1.88 per pound live weight, according to USDA data. After slaughter yields, processing, transport, and retail margins, consumers often pay $4-$8 per pound for ground beef, and far more for premium cuts.

Cultivated meat began at astronomical costs — the first lab-grown burger in 2013 reportedly cost over $300,000.

Today, costs have fallen dramatically, but credible analyses still place cultivated beef well above commodity pricing.

A 2025 techno-economic review concluded that achieving costs below $9 per kilogram (about $4 per pound) would require aggressive assumptions about growth rates, media cost reductions, and facility scale.

Reaching price parity remains theoretically possible but requires breakthroughs across multiple parameters simultaneously.

This explains why early cultivated products target ground meat, nuggets, and blended foods, rather than ribeye steaks.

Scale changes everything — but scale is exactly the challenge.

This brings us to the question of global demand.

Can livestock alone ever meet global beef demand?

If global beef production is roughly 76.6 million tons per year, then replacing even 10 percent would require 7.6 million tons of alternative production annually.

That is not a startup problem. It is an industrial civilization problem.

For perspective, McDonald’s — one of the largest single buyers of beef on Earth — is estimated to use between 100,000 and 300,000 tons of beef per year, depending on patty size and sourcing assumptions. That is a fraction of 1% of global production.

Beef demand does not collapse because cows disappear. It plateaus when land, climate constraints, and price elasticity intervene.

This suggests a more realistic role for cultivated beef: not replacement, but relief.

On the upside, this would also mean you know where your beef comes from.

And relief technologies rarely look revolutionary at first. They look supplemental.

The feasibility question: replacement or pressure valve?

Cultivated meat is unlikely to replace ranching in the near future. But it may be able to feed more people with fewer resources, particularly in dense urban regions where land constraints are severe and logistics dominate cost.

Its true leverage lies in:

- Reducing land pressure

- Buffering climate volatility

- Providing protein security independent of grazing systems

- Enabling localized production near cities

As one industry observer put it:

“We can feed more people with fewer resources by shifting from conventional meat to alternative proteins.”

— GFI Analyst

The cow may not disappear. But it may no longer be the sole biological bottleneck.

Conclusion: when meat becomes manufacturing

If beef can be grown without animals, then meat becomes less about herds and more about infrastructure, energy, and design choices. The steak turns from a product of ecology into a product of engineering.

Whether that future is cleaner, cheaper, or healthier is not predetermined. It depends on how the technology scales, who controls it, and what trade-offs society accepts.

The cow is not obsolete yet. But for the first time in history, it has competition — not from another animal, but from a machine.

Follow us on X, Facebook, or Pinterest