Roman Polanski’s 2002 film The Pianist is based on the true memoir of Polish Jewish pianist Władysław Szpilman. What unfolds on screen is not only a record of Nazi brutality during the Holocaust, but also a rare moment in which humanity briefly interrupts it.

When German Captain Wilm Hosenfeld discovers Szpilman hiding among the ruins of Warsaw, he does not immediately carry out the extermination order expected of him. Instead, he asks Szpilman to play Chopin’s Nocturne in B-flat minor. In that shattered building, music becomes a final refuge. Hosenfeld spares the artist’s life and later provides him with food and a coat, enabling him to survive the war’s final days.

The scene is unforgettable because it exposes a painful truth: Even within a system built for mass murder, individual conscience sometimes survived. Art was not powerful enough to stop the machinery of death, but it was powerful enough, in that moment, to pause it.

If we turn from that historical moment to the present-day Chinese Communist regime, the contrast is stark. In today’s China, victims are not permitted to “finish their song.” There is no allowance for lingering notes, no space for art to offer even a fleeting pause from repression — whether the artist is Chinese or foreign.

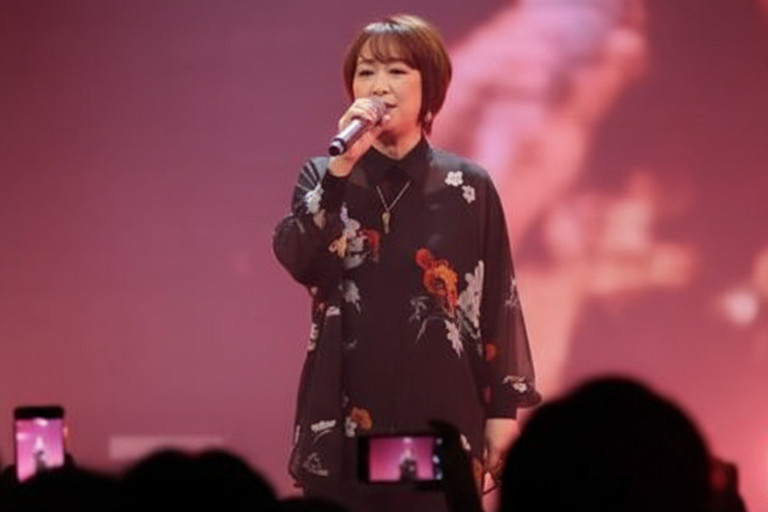

That reality was on display on November 28, 2025, during the Bandai Namco Festival at Shanghai’s West Bund Dome Art Center. Japanese singer Maki Otsuki was in the middle of her performance when, as she reached the chorus, the lights abruptly cut out, the screens went dark, and the music stopped without warning. Two staff members rushed onstage — one seized the microphone, the other pulled her by the arm — and forcibly escorted her away.

Otsuki is widely known across Asia for singing Memories, the 1999 ending theme of the anime One Piece. This was her first performance in China in 26 years.

The audience reaction was immediate. Shock gave way to anger as shouts rang out: “No way!” “Censorship?” “This is so disrespectful!” It was not a technical failure. It was an act of political intervention. While no official explanation addressed the cause directly, the incident occurred amid heightened tensions following remarks by Japanese Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi that Beijing found objectionable.

Organizers later offered only a vague explanation, citing unspecified “external factors.” Yet reporting by the BBC and The Japan Times noted that, on the same day, Japanese pop star Ayumi Hamasaki’s Shanghai concert was also abruptly canceled. A stage that had taken five days to build was dismantled at the last minute. All 14,000 tickets had sold out. Hamasaki ultimately performed alone in an empty venue.

Online reaction was swift. Japanese users on X condemned the cancellations as “thuggish behavior.” On Weibo, Chinese users expressed bitter frustration: “If you’re going to shut it down, at least do it with some dignity — let her finish singing before cutting the power.” Otsuki herself issued a restrained statement on Instagram and X, apologizing to fans and explaining that the performance had been halted for reasons beyond her control. The calmness of her words only underscored the helplessness of the situation. Video clips of the incident spread rapidly across Reddit, Instagram, and other platforms, drawing global attention to the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP’s) heavy-handed interference in artistic expression.

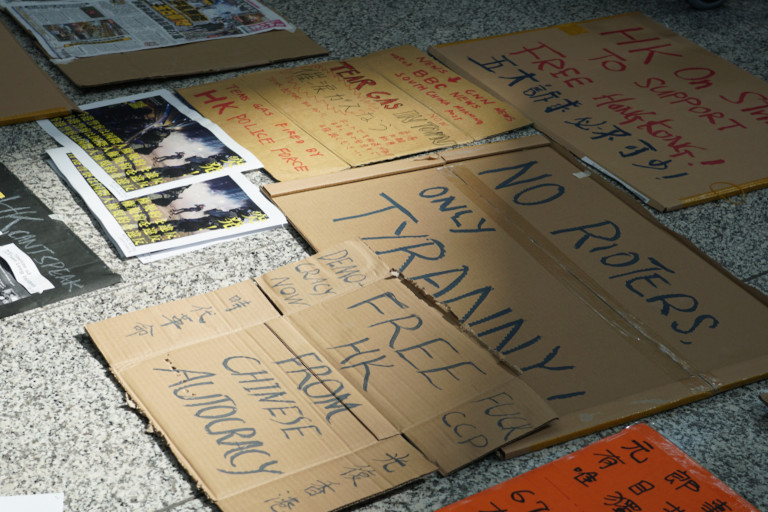

This was not an isolated episode. It fits a long pattern of what can only be described as systematic artistic silencing. In 1989, during the June Fourth crackdown in Tiananmen Square, students sang a revolutionary anthem as tanks advanced, the song swallowed by bloodshed. In 2019, during the siege of Hong Kong Polytechnic University, protesters played piano across the campus before police responded with tear gas and destruction. During the 2022 White Paper Movement, a young woman played piano while holding a blank sheet of paper; police interrupted the performance and arrested participants.

The pattern extends beyond city streets. Uyghur musicians, such as Shohret Tursun, have been detained in so-called re-education camps for playing traditional instruments. Tibetan singer Lhamo disappeared after her music touched on cultural autonomy. Even well-known Chinese artists have not been spared: Fei Xiang was blacklisted for supporting Hong Kong’s democracy movement, while independent musician Li Zhi was driven into exile over lyrics deemed politically sensitive.

In each case, the message is the same. The Chinese Communist Party does not allow artists to finish their final verse. Art is treated not as a human expression, but as a threat — something to be erased through censorship, detention, or disappearance.

The Nazi regime allowed Szpilman to finish his piece because one officer still recognized beauty and compassion in music. The CCP does not make such allowances. It does not pause. It does not listen. And it does not permit the song to end on its own terms.

Translated by Audrey Wang

Follow us on X, Facebook, or Pinterest