Art has always served as a mirror to humanity’s sacred order — its beliefs, values, fears, and ambitions. Throughout human history, art has undergone a profound transformation, reflecting the shifting tides of human morality and culture. At its core, ancient art embodied order, morality, and humanity’s place within the divine cosmos. In stark contrast, much of modern art reflects a rebellion against these very principles, often signaling a broader cultural departure from traditional moral values and the sacred order of existence.

Ancient art: an embodiment of order

The purpose of ancient art: reflecting the divine order

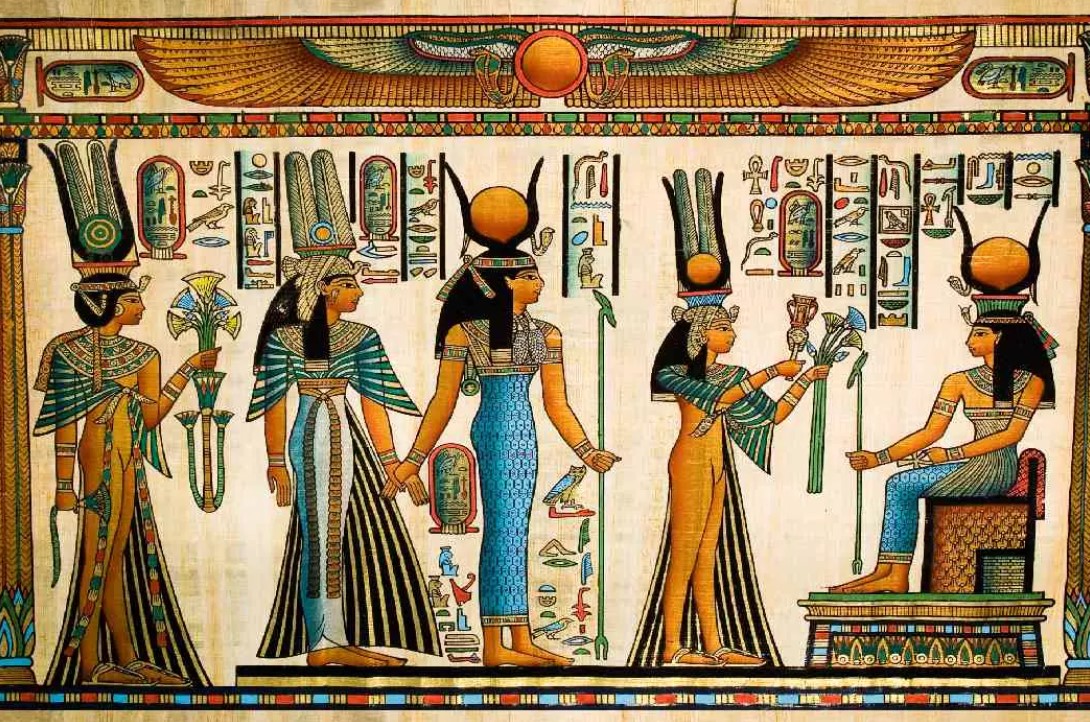

In ancient civilizations, art was far more than personal expression; it was a sacred duty and a communal act. From the frescoes of ancient Rome to the monumental sculptures of Egypt, from Greek temples to Byzantine icons, ancient art sought to visually express humanity’s relationship to the divine and the cosmos. The artist’s role was not to assert individual creativity but to align with transcendent, timeless truths that governed society.

In Egypt, art depicted the pharaoh as a living god, ensuring harmony (Ma’at) between heaven and earth. Greek sculptors, such as Phidias, idealized the human form, seeing in it a reflection of divine perfection and cosmic balance. In medieval Christian art, intricate stained glass windows and illuminated manuscripts aimed to elevate the soul toward God, serving as visual theology for the faithful. Even in early cave paintings, such as those found in the Lascaux or Cosquer caves, there is evidence of ritualistic purpose, possibly linking humanity with nature and the supernatural.

Ancient art was governed by objective standards rooted in metaphysical principles. Beauty was not subjective; it was seen as an expression of order, balance, and virtue. Artists were custodians of cultural and moral stability, ensuring that their works conformed to the higher laws believed to govern the universe. This approach to art fostered a sense of unity and shared purpose, reinforcing the collective values of the society.

The sacred order of craftsmanship: Skill and morality in execution

Creating art in the ancient world required discipline, reverence, and exceptional skill. The execution of a fresco, mosaic, or sculpture was a sacred process, often imbued with religious rituals and strict adherence to tradition. The artist’s technical mastery was seen as inseparable from their moral integrity; the purity of intent was as vital as the precision of the brushstroke or chisel.

Consider the Parthenon sculptures or the Sistine Chapel ceiling — works that demanded not only artistic genius but also profound respect for spiritual and moral ideals. The artist was often anonymous, subsuming personal ego in service of the divine message their art conveyed. This humility reflected the belief that creativity was a gift entrusted to serve something greater than oneself — a community, a faith, or a cosmic order.

The process of artistic creation was itself a form of devotion, a way to participate in the sacred order of the universe. The result was art that not only delighted the senses but also elevated the spirit, reinforcing the moral and metaphysical foundations of society.

Modern art: Rebellion against tradition and divine authority

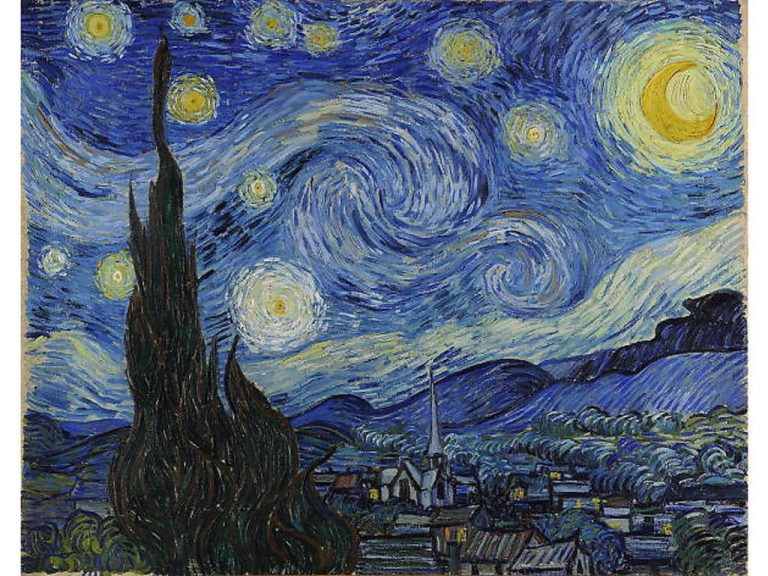

Modern art, which began emerging in the mid-19th century and flourished throughout the 20th, represents a dramatic departure from this value-based tradition. Where ancient art sought alignment with the divine, modern art often seeks to challenge, deconstruct, or even reject it outright.

Movements like Dadaism, Surrealism, and Abstract Expressionism openly defied established norms. Influenced by the Enlightenment and later by the existential despair following two world wars, many modern artists embraced moral relativism, personal subjectivity, and emotional extremism. Figures like Marcel Duchamp, Salvador Dalí, and Jackson Pollock epitomized this break from order, replacing sacred symbolism with personal rebellion.

The French Revolution and the Age of Enlightenment dismantled many of the religious and cultural structures that once defined the purpose of art. Without a shared moral framework, modern art became a stage for individual expression — often chaotic, provocative, and intentionally dissonant. Where ancient art saw beauty as an objective truth to aspire to, modern art often views beauty as arbitrary or even oppressive — a construct to be dismantled in the pursuit of personal freedom.

Cultural consequences of moral relativism in art

The shift from sacred to secular in art has profound cultural consequences. Modern art frequently mirrors the broader societal trend toward moral relativism, where absolute values are replaced with subjective interpretations. This transformation is not merely aesthetic but deeply philosophical, reflecting a society in search of meaning amid the collapse of traditional certainties.

In abandoning shared standards of beauty and morality, much of modern art descends into nihilism — rejecting not only divine order but also any stable reference point for meaning. This is why installations featuring random found objects, deliberately grotesque images, or shocking displays are often praised as avant-garde. They symbolize humanity’s existential crisis and its struggle to find meaning in a world that seems detached from a higher purpose.

While this freedom allows for unparalleled diversity and innovation, it also creates cultural fragmentation. Without a unifying moral or aesthetic standard, art no longer serves as a cohesive cultural narrative but rather as a collection of isolated personal experiences. The result is a society where art can both inspire and alienate, reflecting the fractured nature of modern existence.

The loss of objective beauty and meaning

One of the most striking distinctions between ancient and modern art is their respective relationship to beauty. Ancient artists sought to manifest objective beauty, believed to reflect the divine harmony of the universe. Symmetry, proportion, and balance were not mere techniques but reflections of metaphysical truths.

Modern art often rejects these principles outright. Movements like Abstract Expressionism or Conceptual Art emphasize process over product, idea over execution. In some cases, technical skill is intentionally discarded to focus on raw emotion or ideological statement. This inversion leaves many modern audiences alienated, unsure how to connect with art that often appears inaccessible, confusing, or morally ambiguous.

The loss of objective beauty removes the common ground upon which shared human experience can be built. Without a sense of the sacred or the beautiful, art risks becoming a mere spectacle or a vehicle for shock, rather than a source of inspiration and moral elevation.

Conclusion: The crossroads of art, morality, and culture

The evolution from ancient to modern art reflects a broader human journey — from order to chaos, from the sacred to the secular, from objective moral standards to subjective personal expression. Ancient art, grounded in the divine and moral order, sought to elevate humanity by reminding us of our place within a higher cosmic design. Modern art, in contrast, often rebels against this order, reflecting humanity’s search for meaning in a fragmented, disenchanted world.

As we stand at the crossroads of art, morality, and culture, a question emerges: will future art rediscover the timeless value of order, beauty, and moral clarity, or continue down a path of moral ambiguity and relativism? The answer may well shape not only the art world but the very soul of human civilization.

Follow us on Twitter, Facebook, or Pinterest