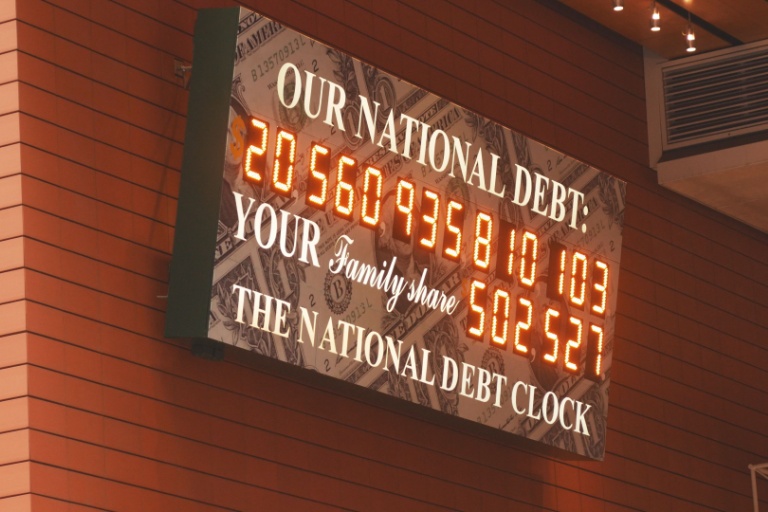

America is sitting on $36 trillion in debt. That number is so significant that your brain basically short-circuits trying to visualize it. It’s not just a spreadsheet entry — it’s real money owed, IOUs stacked like poker chips to lenders both foreign and domestic. People love to say: “China owns us.” But Beijing holds just $750 billion of U.S. debt — a fraction of the total. Meanwhile, China is struggling to cope with $18 trillion of its own obligations. So who owns whom?

The deeper you dig, the messier it gets. U.S. banks hold Chinese debt. Chinese banks hold U.S. debt. European banks hold both. Everyone owes everyone else, resulting in a global IOU network worth $300 trillion — triple the size of the actual global economy. Here’s the uncomfortable truth: Modern civilization is built on debt. It’s not a bug in the system. It is the system.

Debt is older than money

We tend to think of debt as a modern nightmare, concocted by bankers in dark suits. But it’s ancient — older than coins, older than banks, maybe older than organized religion. Picture this: you lend your neighbor a bag of grain in the spring. Come harvest, he pays you back — with a little extra for your trouble — no interest rates. No contracts. Just trust. That’s debt at its core: borrowing from tomorrow to solve a problem today.

Fast-forward to medieval kings and empires. Castles, cannons, and fleets weren’t cheap, and no single lender could foot the bill. So governments started selling debt to the public. By the 1600s, England was financing wars with bonds — IOUs promising repayment with interest. It was revolutionary. Bonds democratized debt. Suddenly, ordinary citizens were funding kings and wars — and profiting from it. Debt had gone from private deals between neighbors to a structural pillar of empire.

The 20th century: Debt goes global

Wars supercharged borrowing. World War I and World War II compelled governments to incur unprecedented debt — not just to fight, but to rebuild entire continents. Then came 1944. At Bretton Woods, the U.S. dollar was established as the dominant currency in the global system, tied to gold. Every other currency is linked to the dollar, and the dollar is connected to the gold reserves in Fort Knox. But there wasn’t enough gold to keep up with growing economies. Cue 1971. Nixon abandoned the gold standard, declaring that the dollar would no longer be backed by gold. Money became fiat currency — backed only by government decree and the promise that people would still believe in it.

And believe they did. With no golden leash, governments could print and borrow freely. From the 1980s onward, debt was no longer just used for wartime purposes. It became the engine of growth itself. Need a school? Borrow. Need a highway? Borrow. Need to pull the country out of recession? Borrow harder.

The $300 trillion question: Who’s owed what?

Here’s where it gets trippy. If the U.S. owes $36 trillion, who exactly is holding the bill? China? Shadowy billionaires in Monaco? Some Illuminati bank vault under Zurich? Not really. Roughly 70 percent of U.S. debt is owed to Americans themselves.

When you drop money in the bank, it doesn’t just sit there in a vault Scrooge McDuck–style. The bank uses it. They buy bonds, they lend, they invest. Currently, U.S. banks hold approximately $1.8 trillion worth of Treasury bonds. Pension funds and insurance companies are stuffed with them. In fact, 60 percent of insurance assets are parked in bonds, quietly growing in the background. So when the U.S. pays interest on its debt, that money flows back into pensions, savings, and retirement funds. It’s a closed loop, a kind of financial perpetual motion machine.

And it’s not just domestic. About 30 percent of the U.S. debt is held by foreign investors. Japan, China, and European banks all park their excess cash in Treasuries. The U.S. borrows. They earn interest. The cycle continues. Zoom out, and it’s clear this isn’t unique to America. Every major country is both a borrower and a lender — the Japanese savings fund and the Brazilian debt. Brazilian debt holders buy American bonds. American pension funds buy Japanese bonds. It’s not a straight line. It’s a web of circular IOUs, with trillions of dollars spinning in circles like a global washing machine.

The perpetual roll-over

Here’s the kicker: governments don’t really “pay back” their debt. They roll it over. When an old loan comes due, they borrow again to pay it off. Yes, it sounds like the financial equivalent of maxing out one credit card to pay off another. And yes, it is, to some extent. But this is the foundation of modern finance. The reason? It fuels growth. Governments borrow, they spend, businesses earn more, workers get paid, workers spend more — the cycle feeds itself. Stop borrowing, and the whole machine seizes up.

Need proof? Look at Greece in 2008. Investors stopped buying Greek bonds. Suddenly, the government couldn’t borrow. The economy collapsed: one in four public workers fired, wages cut by 30 percent, and GDP shrank by a quarter. Austerity turned a recession into a depression. Politicians know this. That’s why no one campaigns on “responsible spending” anymore. Voters expect jobs, welfare, infrastructure — all paid for by the same debt no one really wants to stop accumulating.

Crisis mode: When debt saves the day

Debt isn’t just about growth. Sometimes it’s about survival. When COVID hit, people stopped spending. Economies flatlined. The only thing keeping countries afloat was government borrowing. The U.S. racked up $3.8 trillion in new debt in 2020 alone. China, Europe, and everyone followed. It wasn’t optional. It was triage. Without borrowing, the entire global economy would have ground to a halt. But every new crisis adds another layer to the pile. To repay debt, governments borrow more. The cycle never ends.

The cracks beneath the surface

Here’s the danger: the bigger the debt mountain grows, the more fragile the system becomes. Today, debt-to-GDP ratios of 100 percent are typical. A few decades ago, that was considered catastrophic; however, it’s fine as long as interest rates stay low and investors continue to buy bonds. But what if they don’t?

When lenders get spooked, they demand higher rates. Governments then face a brutal choice: raise taxes, slash spending, or print money. All of those options carry political suicide notes. Printing money is the easiest but also the riskiest. It devalues the currency, triggering inflation. In mild doses, inflation pisses people off at the grocery store. In extreme cases, it torches entire economies. Ask Venezuela. By the late 2010s, prices doubled every few weeks as the government printed its way out of debt. Bread costs millions of bolivars. Life savings evaporated overnight. That’s the nightmare scenario: a debt spiral → inflation → collapse.

Why this won’t end anytime soon

Can this carousel of borrowing and lending spin endlessly? In theory, yes. As long as money continues to circulate, the cycle sustains itself. However, the more debt accumulates, the less room there is to maneuver. Interest payments eat into budgets meant for hospitals, schools, and infrastructure — political fights over spending turn uglier. Every crisis demands another borrowing spree. And yet — here’s the paradox — no one wants to stop. Debt is oxygen. Shut it off, and the global economy suffocates. Keep inhaling, and you risk overdose.

The big picture: Debt as civilization’s double-edged sword

Debt isn’t just a number on a spreadsheet. It’s the engine of modern civilization. It built the highways we drive on, the schools we study in, the armies nations project power with, and the safety nets we cling to in crises. But it’s also a time bomb, ticking louder every year. The U.S. owes $36 trillion. The world owes $300 trillion. And while the system is designed to keep rolling that debt forward, the cracks are visible: slowing growth, political instability, and rising inflation pressures.

The reality? We’re all in on the same gamble. From your retirement fund to China’s balance sheet, everything is tied to the belief that the debt cycle can spin just a little longer. The question isn’t if it stops. The question is when — and what happens next.

Follow us on X, Facebook, or Pinterest