There is an ancient Chinese saying that compares a person of noble character to jade: beautiful, valuable, yet requiring careful shaping to reveal its true worth. Few historical figures embody this ideal better than Empress Ma of the Eastern Han Dynasty, a woman whose deliberate refusal of power became her greatest legacy.

Born around 40 CE, Ma Mingde rose from tragedy to become one of the most celebrated empresses in Chinese history. Her life offers timeless lessons about leadership, integrity, and the wisdom of restraint. At a time when imperial consort families routinely seized power and corrupted dynasties, she chose a different path.

Why Empress Ma’s story matters today

The Eastern Han Dynasty (25-220 CE) learned hard lessons from the Western Han’s collapse. That earlier dynasty had fallen partly because powerful families of empresses accumulated too much influence, destabilizing the government. The founders of the Eastern Han were determined to prevent this pattern from repeating.

Empress Ma understood this history deeply. She became living proof that a person could hold immense influence without exploiting it. In an era of palace intrigue and political manipulation, her commitment to virtue over power made her exceptional. Her posthumous name, Mingde, meaning “Clear Virtue” or “Bright Virtue,” captures how history remembers her.

Early life: A young woman shaped by hardship

Ma Mingde was the third daughter of the famous Han Dynasty General Ma Yuan. Her early years taught her resilience under circumstances that would break most people. When her father died, Ma Mingde was only thirteen years old. Her mother’s mental health deteriorated from grief, leaving the household in chaos. Rather than succumb to these difficulties, the young girl stepped forward to manage the entire family. She handled both major decisions and daily affairs with the competence of an experienced adult.

According to historical records, by age ten, she was already capable of directing household affairs. When a physiognomist examined her, he predicted she would achieve great honor. These early experiences forged the character that would later define her reign.

Rise to the Imperial Court

In 52 CE, at age thirteen, Ma Mingde was selected to join the court of Liu Zhuang, the crown prince who would later become Emperor Ming. She entered a world of competition and intrigue, where noble women vied for the prince’s favor. Ma Mingde distinguished herself through a different strategy: genuine virtue. She treated everyone around her with respect and courtesy, from fellow consorts to servants. This approach gradually made her beloved by all who knew her.

The crown prince’s mother, Empress Dowager Yin, noticed the young woman’s exceptional character during their early interactions. She praised Ma Mingde’s intelligence and propriety, recognizing qualities that mere beauty could never match.

Becoming empress through virtue alone

When Emperor Ming prepared to select his empress in 60 CE, he consulted his mother for advice. Empress Dowager Yin’s response was immediate and emphatic: “Lady Ma is the crowning virtue of the women’s quarters. She is the very person to be made empress!” Thus, at age 21, Ma Mingde became Empress Ma. The selection was remarkable because it rested entirely on her moral character rather than political connections, family power, or physical beauty alone.

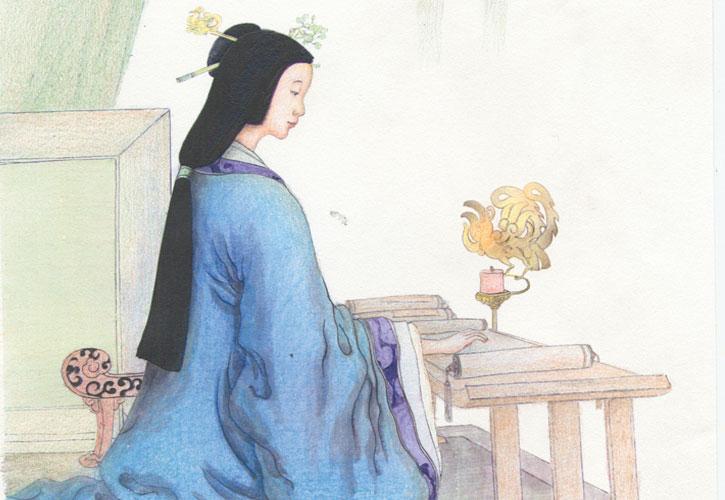

After assuming her position, she conducted herself with even greater modesty than before. Historical records note that she always wore simple robes of coarse-woven silk with no decorative border at the hem. This humble choice of clothing, despite having access to the finest silks in the empire, symbolized her values and set a humble example for the entire court.

A scholar and wise counselor

Empress Ma possessed more than moral virtue. She was also deeply learned. She could recite the Book of Changes in its entirety and mastered many classical Confucian texts. She went on to become a writer herself, contributing to the court’s intellectual life.

Though she preferred not to interfere in state affairs, she stepped forward when her conscience demanded it. Emperor Ming, normally a strict ruler, came to value her political insights. She offered analysis and constructive solutions that directly improved the country’s governance.

The Prince of Chu conspiracy

Her most significant intervention came during a crisis in 71 CE. Emperor Ming’s brother, Liu Ying, the Prince of Chu, became entangled in a conspiracy. The emperor responded with mass arrests, tortures, and executions. Thousands of people faced punishment, many only remotely connected to the actual plot.

Empress Ma interceded on behalf of the accused. With careful words and quiet influence, she convinced Emperor Ming to temper his response. The campaign of punishment tapered off, saving countless innocent lives. This single act of compassionate intervention demonstrated that her influence, when exercised, served justice rather than self-interest.

Motherhood without birth: Raising the future emperor

One of the most touching aspects of Empress Ma’s story involves the son she raised but never bore. Emperor Ming assigned her to care for Liu Da (later renamed Liu Dan), the child of another consort named Lady Jia. The emperor’s instruction was simple: “I only hope that you will not fail to show the child affection although he is not your own son.”

Empress Ma exceeded every expectation. She refused help from servants, wearing herself out attending to the boy’s every need. The care and motherly love she gave him surpassed what other royal wives showed their biological children. Liu Dan grew to adore her completely.

When Liu Dan later became Emperor Zhang, he knew the truth of his birth. Yet he treated Empress Ma as his true mother in his heart, a testament to the genuine bond she had created through love rather than blood.

The ultimate test: Refusing power for her family

The true measure of Empress Ma’s character came after Emperor Ming died in 75 CE. Her adopted son Liu Dan ascended to the throne and named her Empress Dowager. In this position, she could have done what so many empress dowagers before her had done: elevate her family to positions of power and wealth.

Emperor Zhang wanted to honor his adoptive mother by conferring the title of Marquis upon her three brothers. This was a standard practice, and no one would have questioned it. Empress Dowager Ma refused. She wrote an edict forbidding the honors: “The Ma family has not made any contribution to the country. Right now, there is a major drought, and our people are suffering. If you must honor them, wait until the weather is good and our border is calm.”

Four years later, when conditions improved, Emperor Zhang finally bestowed the titles upon her brothers. Even then, the wise empress dowager warned them against exerting influence at court. Following her guidance, they resigned from their official posts and withdrew entirely from political affairs.

This deliberate restraint was revolutionary. During the Eastern Han Dynasty, many emperors died young, leaving child sons to inherit the throne. Most empress dowagers relied on their own families to run the country, often resulting in corruption and tragedy. Empress Dowager Ma was the only exception.

A legacy that endures

Empress Ma lived her entire life in a modest, low-key, and frugal way. She died in 79 CE at the age of 41, but her influence extended far beyond her lifetime. Her example helped establish the Eastern Han policy of restraining consort clans, which contributed to the dynasty’s stability during its early and middle periods. Her leadership demonstrated that true strength often lies in restraint and that wisdom means limiting one’s own power for the broader good.

Chinese historians remember her as one of the most virtuous empresses in history. Her story appears in classical texts as a model of ethical leadership. Unlike rulers who are celebrated for conquests or wealth, Empress Ma is honored for what she chose not to take.

Lessons for modern leaders

The story of Empress Ma offers insights that remain relevant today. Her approach to leadership challenges many contemporary assumptions about power and success. She understood that influence built on character outlasts influence built on position. She recognized that the greatest service sometimes means stepping back rather than stepping forward. She proved that refusing to exploit an advantage can be more powerful than seizing every opportunity.

For parents, her story illustrates that love transcends biology. For leaders, it demonstrates that integrity and restraint earn lasting respect. For anyone navigating power dynamics, she shows that choosing virtue over advantage is not weakness but wisdom. Like Emperor Taizong of Tang, who valued accepting criticism, or Emperor Kangxi, who prioritized virtue over talent in his officials, Empress Ma exemplifies the traditional Chinese understanding that moral character forms the foundation of good governance.

In a world that often celebrates accumulation and ambition, Empress Ma reminds us that the most valuable treasures are sometimes the ones we choose not to take.

Follow us on X, Facebook, or Pinterest