The Great Famine in mainland China, also known as the “Three Years of Difficulties” or the “Three Years of Great Famine,” occurred between 1959 and 1961. What I witnessed and experienced in the countryside, what I saw and experienced in the city when returning home, and what I later heard from various people were all true and heartbreaking stories.

In the countryside, policies like the “communal kitchens,” “fire bans” (prohibiting farm households from lighting fires), and “no fleeing to beg for food” led to reduced agricultural output. Yet taxes and state-purchased grain were collected based on inflated production figures. Rural grain reserves were nearly depleted, leaving farmers dependent on state-rationed supplies. In Changshou County, farmers received a daily ration of two liang (approximately 100 grams), yet often failed to collect it on time.

At that time, Changshou belonged to Fuling Prefecture. Once, when Fuling diverted grain to support Shanghai, farmers went without rations for 45 days. What did they eat? Vegetable roots and wild greens — straw, roots, leaves, and husks of crops like rice, wheat, barley, corn, and sorghum that people wouldn’t normally eat in non-disaster years. This included corn cobs, rice husks, and tuber crops’ leaves, stems, and roots. And the stalks, roots, leaves, bark, and fruits of wild plants, such as elm, acorns, taro, hemp seeds, lycoris, wild yam, giant lily, wild amaranth, and locust leaves.

After these resources were exhausted, some areas discovered that white fan clay (also called Guanyin soil) was edible. Farmers said: “Guanyin Bodhisattva has distributed grain,” kneading the clay into balls, steaming them, and eating them. Most people who consumed it couldn’t defecate and died. Everyone suffered from swelling diseases while working overtime. Deaths were commonplace at that time.

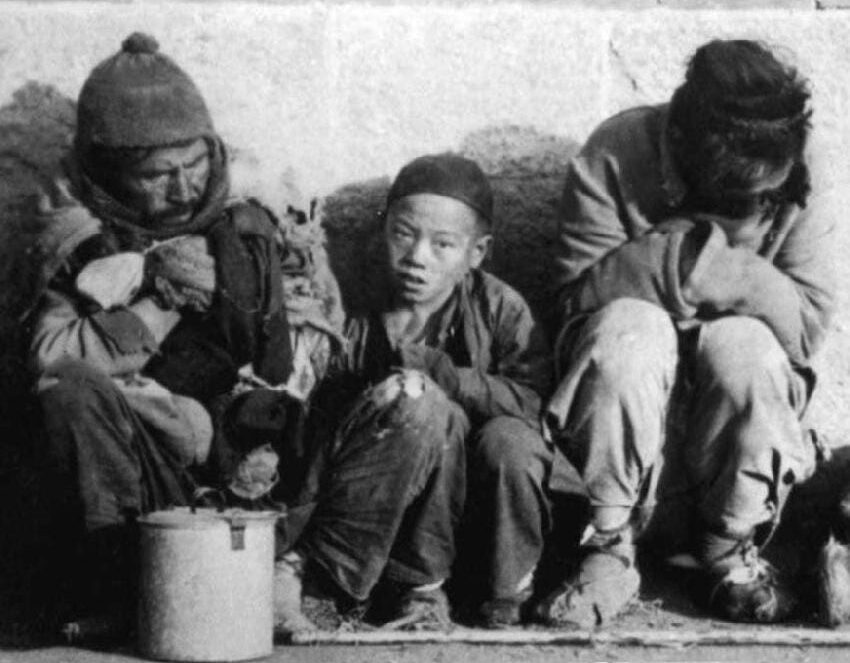

There were corpses everywhere in China from the Great Famine

Walking down the street, we often saw corpses by the roadside. Others, leaning on walking sticks, would stumble and fall, only to get up again. I met a man from Jiayang who was pedaling a tricycle in Chengdu. When he spoke of the Great Famine, he said: “In ’61, my entire family died, leaving only me. With no choice, I climbed onto a coal-hauling train and went to Chengdu. I was caught immediately. At 11, I looked like a 6- or 7-year-old from starvation.

When asked about my identity, I said nothing but cried that my family was dead. They sent me to an orphanage to survive. This relentless exploitation of farmers made survival impossible. Back then, peasants had a rhyme: “Grain is the priority, and wipe out cotton and oil. Steel is the priority, and cut down all trees.” They also said that even the human race would be gone by 1962, with another Great Leap Forward.

After years of firsthand experience, every upright, kind-hearted person who doesn’t blindly follow the crowd must carefully reflect: Is this really what “building a new countryside” looks like? Adults arrested were labeled “unregistered migrants” and sent to detention centers, subjected to forced labor or brutal beatings. This criminal system was only abolished in 2003 after the death of Sun Zhigang, a college student working in Guangzhou without a “temporary residence permit,” who was beaten to death in a Guangzhou detention center.

Translated by Audrey Wang and edited by Amanda

Follow us on X, Facebook, or Pinterest