Mark Zuckerberg has spent two decades bending reality to his will. From a Harvard dorm room prank to an empire that dictates how billions connect, fight, love, and spiral into conspiracy rabbit holes — his story is the stuff of modern myth.

But now the emperor of attention may finally be facing something he can’t code his way out of: a historic antitrust trial that could strip him of Instagram, WhatsApp, and the unchecked dominance he’s built. And the timing is no accident. Just as the government sharpens its knives, Zuckerberg is suddenly chummier with Donald Trump than a UFC promoter at Mar-a-Lago.

So the real question isn’t just whether Zuckerberg’s empire collapses. The question is whether he’s trying to trade political favors for survival — and what happens to the rest of us if he wins.

The chameleon king

Here’s the thing about Zuckerberg: He’s always morphing. In his early days, he was the awkward hoodie kid who claimed Facebook was just about “helping people connect.” Then came the magazine covers, the $17 billion valuation, the clumsy attempts at charisma.

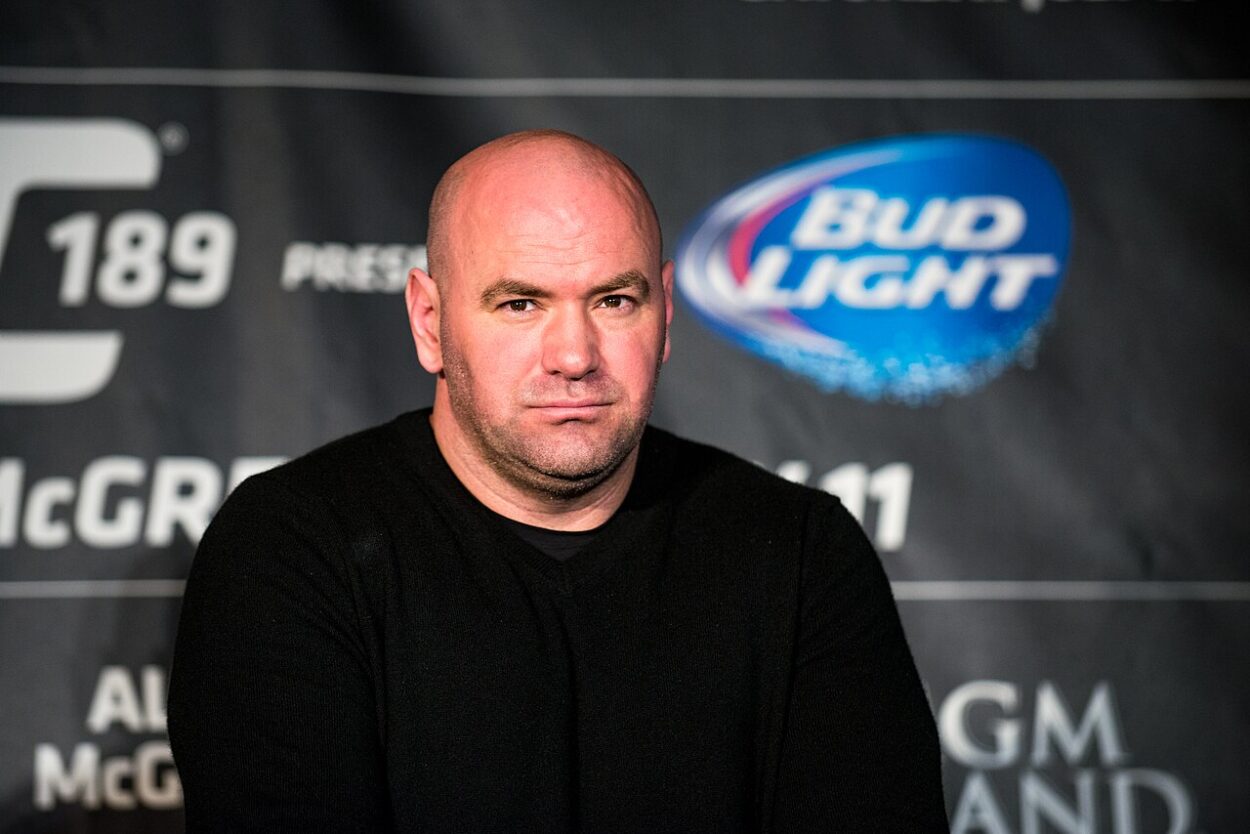

Now, he’s thick-necked, jiu-jitsu trained, grinning next to Dana White, fist-pumping American flags. A political rebrand for a man who doesn’t do anything by accident. As one whistleblower put it: “It’s whatever gets him closest to power.” And right now, what Zuckerberg wants from power is brutally simple: protection.

The trial that could break Facebook

This spring, the Federal Trade Commission kicked off a trial that could decide the fate of Meta itself. At stake? Whether Facebook’s acquisitions of Instagram and WhatsApp were not savvy business deals but illegal monopolization. The FTC’s Lina Khan, a millennial trustbuster straight out of central casting, doesn’t mince words: “This case is important because it’s taking aim at Facebook’s illegal monopoly power and undoing that monopolization.”

Her weapon? Antitrust laws written in the analog age are now being resurrected for the digital battlefield. Meta’s counterattack? Throw armies of lawyers at the case, argue the market is everything from TikTok to Netflix, and smear Khan as “biased” because she dared to critique Big Tech before taking office. But behind the courtroom drama is a deeper, older Zuckerberg instinct: when threatened, buy, copy, or crush.

The hot-or-not origin story

Rewind to 2004. Zuckerberg’s empire began not as a revolutionary idea but as a petty, misogynistic prank. “Facemash” — a hot-or-not ranking site for Harvard women — was the proto-Facebook. It was gross, pathetic, and yet it planted the seed. When the site expanded into “TheFacebook,” it became a rite of passage for college students. Everyone wanted in. And once the gates opened to the general public, everyone was in. Zuckerberg had discovered the most valuable natural resource of the digital era: our attention.

The iPhone problem

Here’s the twist: Facebook’s rise predated the smartphone revolution. It was built for laptops, dorm rooms, and digital cameras. Then came the iPhone — a tectonic shift. Suddenly, Zuckerberg’s kingdom looked clunky and vulnerable. Startups like Instagram figured out what Facebook couldn’t: mobile-first design that didn’t suck. With just 13 employees, Instagram grew like wildfire, hitting 100 million users.

Zuckerberg’s solution? Drop a billion dollars on the table. Buy the threat. The same playbook repeated with WhatsApp. Only this time, the price tag was a jaw-dropping $19 billion. Internally, Facebook literally called it a “land grab.” WhatsApp wasn’t just another app — it was the one company that could dethrone Facebook. So Zuckerberg did what any empire builder does: absorb the rival, rewrite the rules, and keep marching.

Privacy vs. profit

Here’s the irony: WhatsApp was built on the exact opposite philosophy. No ads. Minimal data collection. A dollar a year subscription. It was the anti-Facebook. Once Meta took control, those privacy promises evaporated. WhatsApp’s founders — who could have pocketed billions in stock — walked away instead. That’s how hostile Zuckerberg’s world had become: even billionaires would rather walk than bend to his vision.

Monopoly, or just good business?

Fast forward: Instagram now makes up more than half of Meta’s U.S. revenue. WhatsApp tripled its user base. Zuckerberg’s net worth exploded from $33 billion to $184 billion. The FTC calls this monopoly abuse. Meta calls it “smart business.” And the courts? Well, that’s the problem. Antitrust law in America has been gutted since the Reagan era. Judges tend to ask: “Are consumers paying more?” Facebook’s answer: “No, it’s free.” Never mind the actual cost: democracy-destabilizing disinformation, a generation addicted to dopamine loops, and the slow strangulation of innovation.

The politics of survival

But Zuckerberg isn’t betting on courts alone. He’s betting on politics. After 2016, when Facebook was blamed for turbocharging Trump’s rise, Zuckerberg launched a performative apology tour. It flopped. So he pivoted. Suddenly, he’s cozying up to Trump. Mar-a-Lago dinners. $1 million inauguration donations. UFC President Dana White is on Meta’s board. And in whispers behind closed doors: a request. Kill the FTC lawsuit. If that sounds conspiratorial, remember this: Meta reportedly countered a proposed $30 billion settlement with an offer of just $500 million. That’s pocket change compared to its revenue. Translation: Zuckerberg thinks he can buy his way out of accountability.

Can you break the Internet?

Here’s the wild part: breaking up Meta wouldn’t fix everything. But it would pry open the iron grip one man has held over how billions of us interact. Think about it. Entire generations of alternative platforms — privacy-focused, innovative, less manipulative — never got a chance to breathe. Facebook’s network effects suffocated them in the crib. As journalist Jason Koebler points out: “There are dozens of other social media platforms that tried to become popular but never were able to get a foothold because Facebook already had that massive network effect.” A breakup could unleash that suppressed innovation. But only if the government actually wins.

Enter the metaverse (and exit reality)

Meanwhile, Zuckerberg’s already plotting his escape route: the Metaverse. Billions poured into a headset-driven world that, so far, nobody really wants. Legless avatars. Empty conference rooms. Corporate cringe. Stripped of jargon, it’s the same playbook: capture your attention, sell it to advertisers — just with goggles strapped to your face. Even Meta’s investors call it a money pit. But Zuckerberg can’t quit. If his empire cracks, the Metaverse is his Ark. And now, like everyone else in Silicon Valley, he’s chanting the AI mantra. AI coworkers. AI holograms. AI friends for the friendless. Sounds like a dystopian Black Mirror episode. But for Zuckerberg, it’s the next frontier of monetizing loneliness.

Why this matters for the rest of us

So what happens if Zuckerberg loses? Instagram and WhatsApp could spin out, maybe even rediscover the values they once claimed — privacy, innovation, actual connection. If he wins? The empire survives, more consolidated than ever, emboldened to keep mining our lives as data gold. And we’re left with the same question we’ve faced since 2004: Do we want our digital lives defined by one man’s survival instinct?

The digital emperor has no clothes

Mark Zuckerberg has always been a mirror. In him, we see the worst of Silicon Valley’s mythmaking: the hoodie genius, the monopolist, the rebranded gladiator. But strip away the mythology, and you see something simpler: a man desperate to cling to power, bending the world around him so he doesn’t have to bend himself. If the government wins this case, Zuckerberg becomes just another billionaire with a bloated product and a fading dream. If he wins, he cements his role as digital emperor of the 21st century. Either way, the outcome will shape how we connect, how we argue, and how we live online — for decades to come. And maybe, just maybe, it’ll finally force us to ask the question Silicon Valley never wants answered:

What would a digital world without Mark Zuckerberg actually look like?

Follow us on X, Facebook, or Pinterest