Cheng Kaili, secretary-general of the “Pro-Taiwan Anti-Communist National Revival Party” and a former Taiwanese businessman, still feels a chill down his spine when recalling his business days in Beijing two decades ago.

One Saturday afternoon, he was in his office waiting for a familiar friend — a Tianjin “Foreign Trade Office” cadre with whom he had often dined over the past six months. When the man entered, he skipped the usual pleasantries, pulled another business card from his pocket, and revealed his true identity: an officer from China’s Ministry of State Security.

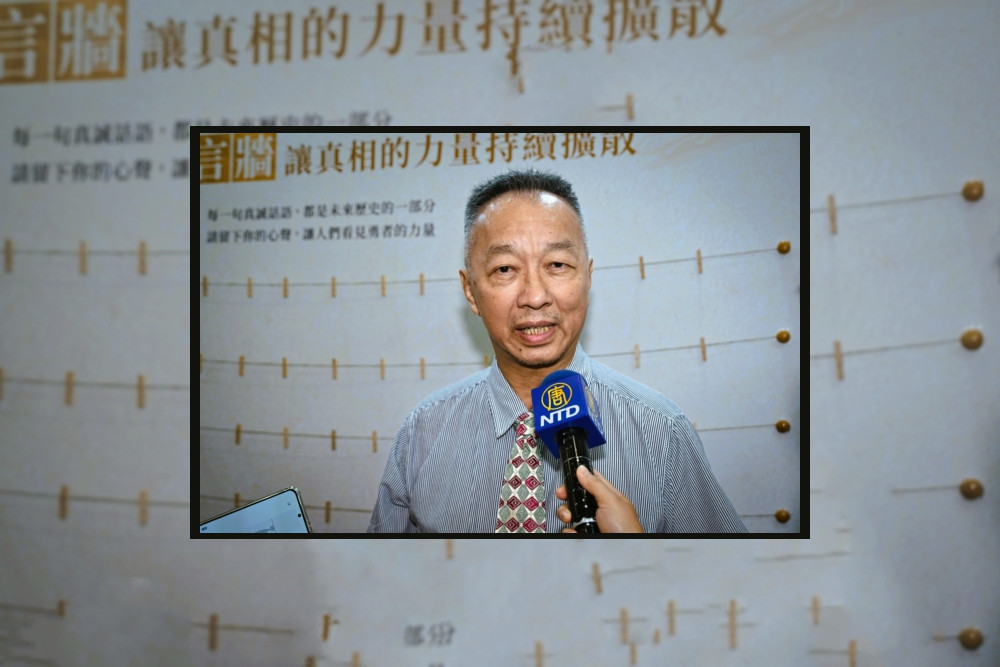

In an interview with The Epoch Times, Cheng said the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has long operated a detailed playbook for its “united front” operations targeting Taiwan — ranging from lavish “red carpet banquets” in villas to infiltration through temples, veteran circles, and business networks.

Recruited after six months of observation

The officer got straight to the point: “I’ve been observing you for six months. You seem upright — I’d like your help.”

Cheng was startled. “Why me?” he asked, half-joking that he was a nobody. The officer replied casually that Cheng wouldn’t have to do much — only “bring back some newspapers and magazines” to Taiwan.

Cheng immediately refused. “Don’t try to fool me,” he said. “You could get that online. Your next step would be asking me to take photos at an airbase.”

The encounter triggered a memory from years earlier. Before his business ventures in China, Cheng had served as a member of the New Party’s central committee in Taiwan. One day, a senior party figure — a now-deceased National Assembly representative and former legislator — called unexpectedly and asked for a ride on a trip down south. They eventually stopped along a desolate coastline in Yunlin County, where the senior official silently began taking photos of the shoreline.

“I thought it was strange at the time — why photograph an empty beach?” Cheng recalled. “Years later, I realized that stretch of coast would be perfect for an airdrop. If the CCP ever invaded Taiwan, those photos could have been reconnaissance materials.”

Overlaying that old memory with the state security officer’s request, Cheng said he was certain: “Had I agreed, sooner or later they would have asked me to photograph military facilities or trapped me with money or women.” He believes this shows how deeply the CCP was already trying to buy off Taiwanese political figures back then.

From ‘cultural China’ to medical corruption

A second-generation mainlander whose parents came to Taiwan from Henan with the Nationalist government, Cheng grew up steeped in traditional Chinese culture. In 2001, he went to Beijing to start a medical equipment company, confident that shared language and heritage would help him in business.

“On my first day, I told my staff: ‘I identify with cultural China, not communist China,’” he said. He introduced a Friday “tea culture,” personally brewing Taiwanese high-mountain tea so employees could speak freely. “If you have criticisms, say them at the tea meeting, not behind people’s backs,” he told them. His open style won respect — “They all said: ‘Boss Cheng carries himself with dignity.’”

While studying at Beijing University of Chinese Medicine, Cheng made friends with professors and hospital directors, which helped him expand his business from northern to northeastern and northwestern China.

He discovered that hospital leaders across China often socialized privately and were surprisingly candid in their discontent. “Almost everyone I met at those dinners criticized the Communist Party. None of them expressed support,” he said. “Under tight surveillance, people were too afraid to speak honestly — terrified of being reported. Because I was Taiwanese and a business contact, they dared to open up. That’s when I realized: inside hospitals, not one person sincerely supports the Party.”

Hidden dealings in medical procurement and the dark use of ECMO

Cheng also saw how deeply corruption ran in hospital procurement.

For heart-surgery equipment, the key decision-makers were always the same five people — the hospital president, vice president, equipment director, cardiac-surgery chief, and anesthesia chief. “Once they’re taken care of, bidding is just a formality,” he said.

At one hospital in northeast China, a department head fancied a Honda CR-V. “I paid for it in full that day. Other suppliers had only made verbal promises,” Cheng recalled. The next day’s open bidding was pure theater — the director publicly questioned the weaknesses of other products, making Cheng’s equipment stand out.

But the most shocking revelation came from the use of ECMO (extracorporeal membrane oxygenation) machines. At a hospital near a coal-mining area, administrators wanted to buy ten ECMO units. The hospital was small, so Cheng asked why. The director explained that Beijing had imposed a “death quota” — mining accidents could report no more than five deaths per year.

“When trapped miners were rescued, they’d be put on ECMO to prove they were ‘still alive,’” Cheng said. “Even if they died days later, it wouldn’t count as an on-site fatality. If twenty actually died, only five would be officially reported.”

Doctors also used ECMO to conceal surgery deaths. “If a patient died on the operating table, doctors couldn’t say so immediately,” Cheng explained. “They’d start ECMO to keep blood circulating and tell families the patient was in critical condition and being resuscitated. It let them move the patient to intensive care and delay death for a few days — easing family reactions and avoiding immediate disputes.”

“ECMO is supposed to save lives,” Cheng said, “but under this system, it became a shield against statistics and accountability.” He added that hospital staff once told him: “Mr. Cheng, one of your Taiwanese doctors is here again — selling ECMO machines!”

Witnessing a suspected organ harvesting site

Cheng said he even saw what appeared to be a facility for forced organ harvesting.

A Korean classmate at Beijing University of Chinese Medicine once invited him to visit a “Korean-run organ transplant hospital” — a lavishly furnished floor within a major Beijing hospital. The staff claimed they could “find a match within a week” and offered to make him their “Taiwan representative,” brokering patients seeking organ transplants in China.

“Waiting lists in Taiwan take three to five years — how could they do it in a week?” he wondered. The Korean explained that the organs came from executed prisoners. Cheng declined.

Years later, when international media and Falun Gong practitioners exposed the CCP’s organ-harvesting crimes, Cheng recalled that hospital and said it made his hair stand on end. He suspects ECMO may have played a key role in keeping donors’ organs viable during the process. “To extract a heart or lungs, you have to maintain blood circulation temporarily,” he said.

Cheng’s experiences exposed a side of China’s medical world — and the political machinery behind it — that few outsiders ever see. His story offers an unsettling glimpse into how power, profit, and secrecy intertwine beneath the surface of ordinary business, setting the stage for the more profound revelations he would later share about the CCP’s influence beyond the mainland.

Translated by Chua BC

Follow us on X, Facebook, or Pinterest