Xu Jiatun became the CCP’s “special envoy” in Hong Kong during the crucial period of Sino‑British negotiations over the territory’s future. Operating through the Xinhua News Agency — which served as Beijing’s de facto embassy — Xu Jiatun was effectively the “Shadow Governor,” building a parallel power structure beneath the British administration. After arriving in Hong Kong, he carried out extensive united front work under the banner of making friends and winning favor among political and business circles.

Martin Lee, founder of Hong Kong’s Democratic Party, recalled meeting Xu Jiatun several times, saying: “Once, at lunch, he told me not to worry too much. Beijing had already sent about 50,000 people to Hong Kong, working in various sectors — government departments and professional fields. If the British withdrew before the handover, these people would step in.” This “parallel civil service” was meant to take over if the British exited abruptly, so the CCP’s grip on the city’s infrastructure would be instantaneous.

The British, before leaving, made arrangements to safeguard their interests. Xu Jiatun recalled: “We countered them point for point. At the time, I controlled hundreds of millions in special funds — wasn’t that exactly what they were for?” He admitted he gave HK$100,000 to veteran journalist Luk Keng, who refused to accept it and returned it. When asked by reporters who else he had funded, Xu Jiatun replied mysteriously: “I can’t say. If I did, it would cause chaos. Some things I can never reveal, not even until death.”

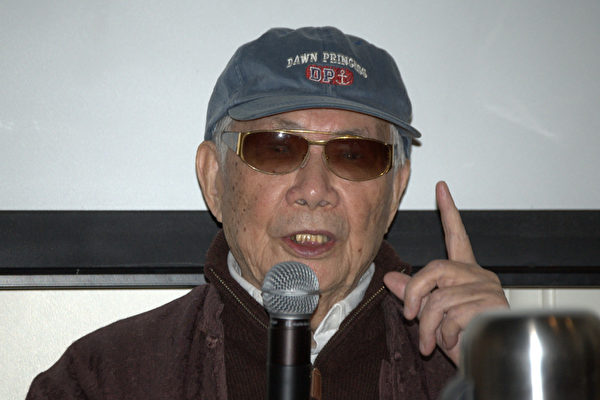

In 2012, during an interview, Xu Jiatun bluntly described himself as “the spy chief.” He said that while in Hong Kong, he knew all the intelligence and united front networks, but insisted he never betrayed friends or leaked secrets, so underground networks remained intact. Unlike his more rigid successors, his strength lay in his ability to blend intelligence gathering with genuine social diplomacy.

Accusations of ‘selling out the country’

Xu Jiatun’s successor at Xinhua News Agency Hong Kong, Zhou Nan, represented the Party’s “hardline” shift. In his memoir, Zhou wrote that Xu Jiatun “betrayed and fled,” viewing his flexible diplomacy as a sign of weakness. What was meant by “selling out the country”? Xu Jiatun recalled: “After June Fourth, Hong Kong people’s confidence in Beijing, the CCP, and ‘one country, two systems’ was badly shaken — already fragile, it nearly collapsed. My main task was to restore their confidence, and I did much work toward that.”

He recounted that So Hoi‑man, the Austrian son‑in‑law of shipping tycoon Bao Yugang, once brought him a proposal signed by more than ten Hong Kong elites. It offered to pay HK$10 billion to lease Hong Kong from China for ten years under self‑rule. Xu Jiatun was astonished. He asked if Bao had approved, but So was evasive. Xu Jiatun suspected Bao preferred not to appear directly. Xu Jiatun told him: “I don’t think Beijing will agree, but I’ll report it. Whatever Beijing replies, I’ll convey to you. I advise you to stop here — spreading it further would harm Hong Kong, China, and yourselves.”

Xu Jiatun later reported the proposal to Jiang Zemin during a Party meeting. Jiang did not comment, but agreed Xu Jiatun could forward it to the Central Committee and Deng Xiaoping. He then sent a telegram. Within a month, Xu Jiatun overheard officials at the Hong Kong and Macau Affairs Office calling the idea “simply treason.” Xu Jiatun explained he had cleared the telegram with the General Secretary. He insisted that, as Beijing’s representative, he was only truthfully reporting Hong Kong opinion — a role the Party’s “hardliners” could not distinguish from betrayal.

Unable to return home

After moving to the United States, Xu Jiatun repeatedly petitioned the CCP leadership under Hu Jintao to allow him to return to China, but was denied each time. His old comrades in Jiangsu also appealed on his behalf, without success. The Party’s memory was long; his flight in the wake of the 1989 crackdown remained an unforgivable stain.

In 2004, his wife, Gu Yiping, died in mainland China. Xu Jiatun’s children requested permission for him to return, but the CCP refused, forcing him to mourn from across the Pacific. In 2013, at age 97, Xu Jiatun visited Taiwan. It was a poignant moment — standing on Chinese soil that was beyond the Party’s reach. He told local media: “I have always wanted to go back, I am always prepared, but Beijing has never agreed. Coming to Taiwan, I feel deeply moved — it feels like returning home.”

Despite appeals from Xu Jiatun himself, his family, and friends, his wish was never granted. He remained a man without a country, living in a quiet suburb of Los Angeles while his heart remained in the politics of a homeland that had erased him. On June 29, 2016, after 26 years in exile, Xu Jiatun died peacefully at his home in Los Angeles at the age of 100. Though expelled from the Party, he kept the secrets of his intelligence work in Hong Kong until his final breath.

His departure was meant to avoid disaster, not to betray. He hoped one day to return, but the CCP permanently rejected him, leaving him barred from his homeland until his death. He died an enigma — a loyal “Spy Chief” who was too liberal for the regime he served, and a diplomat who took the secrets of a city’s transformation to his grave.

See Part 1 here

Translated by Cecilia and edited by Helen London

Follow us on X, Facebook, or Pinterest