Within Japan’s shrines lies a rather intriguing phenomenon: Three historical figures from China are enshrined in what the Japanese consider their most sacred places.

Given the complex historical ties between China and Japan — including the invasion of China and the subsequent war of resistance in modern times — what kinds of figures could transcend national borders and ethnic sentiments to earn such special reverence and remembrance from the Japanese people? The answer lies not in political alignment, but in the unquestionable, tangible blessings each figure bestowed upon the lives and culture of the ordinary Japanese people. Let us recount their stories.

Xu Fu: Crossing the sea to Penglai to spread civilization

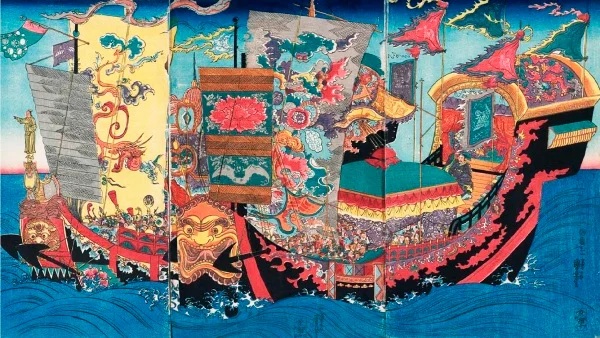

In 219 B.C., after unifying the six states, Emperor Qin Shi Huang began pursuing the secret of eternal life. Among the many alchemists, Xu Fu stood out. He claimed that in the East Sea lay the three immortal mountains where the elixir of life grew. Convinced by his words, the First Emperor ordered him to lead three thousand young men and women, carrying ample provisions, tools, and supplies, on a voyage.

Xu Fu never returned to the Central Plains. According to Japanese historical records, Xu Fu and his entourage ultimately reached the Japanese archipelago, where they settled. Xu Fu did not arrive empty-handed. He brought thousands of young, strong laborers, and more importantly, the advanced civilization of the Central Plains of China. At that time, Japan was still in a relatively primitive agricultural era.

The iron smelting techniques, agricultural knowledge (especially rice cultivation methods), medical and pharmaceutical expertise, and various crafts greatly propelled the development of local society forward.

The impact on civilization

In the hearts of the Japanese people, Xu Fu is revered as “Xu Fu, Minister of Emperor Qin Shi Huang” or “Xu Fu the Immortal.” His status approaches that of a “Founder of Enlightenment” and “Father of Civilization.” Many Japanese scholars believe Xu Fu’s arrival marked Japan’s transition from the Jōmon to the Yayoi period, a pivotal turning point in Japanese civilization. While the specifics of his mission are shrouded in legend and cultural metaphor, his status as the primary conveyor of high Chinese culture remains undisputed in Japanese folklore.

The shrine

Over 50 sites and shrines associated with Xu Fu exist nationwide. The most renowned is the Xu Fu Shrine in Shingū City, Wakayama Prefecture, believed to be his first landing site. This shrine, often maintained by local lineage groups, features Xu Fu’s tomb and a statue. Every October, a grand “Xu Fu Festival” is held, attracting large numbers of citizens who often participate in rituals and parades to honor his enduring legacy.

Chiang Kai-shek: ‘Repaying hatred with virtue’

Chiang Kai-shek, a pivotal figure in modern Chinese history, has a little-known chapter recorded on a tablet in a Japanese shrine. On August 15, 1945, Japan announced its unconditional surrender, ending 14 years of war against China. By the war’s end, Japan lay in ruins.

In his 1945 radio address to Japan, Chiang made a decision that stunned the world: He would handle Japan’s war reparations with restraint and protect Japanese military personnel and civilians in China. Guided by the Confucian principle of “Repaying Hatred with Virtue” 以德報怨, he understood that demanding crushing reparations would trigger Japan’s complete societal collapse, leading to instability detrimental to East Asia.

He ensured the swift and safe repatriation of more than 2 million Japanese nationals, providing them with basic necessities and arranging transport ships. His subordinates strictly enforced these directives, assuring the secure evacuation of millions.

Basis for reverence

In Japan, especially among the older generation who lived through World War II, Chiang Kai-shek is regarded as a benefactor — a savior. This gratitude is rooted in his humanitarian decision, which enabled postwar Japan to begin reconstruction without being utterly crushed by punitive measures.

The memorial

After Chiang Kai-shek’s death, Japanese civic groups and organizations of repatriated expatriates established a memorial tablet and monument for him at Izusan Shrine in Atami. The inscription reads explicitly 以德報怨 (Repaying Hatred with Virtue). Every year on the anniversary of his death, Japanese citizens come to offer flowers and pay their respects at this monument, which is a powerful example of reconciliation enshrined in a sacred space.

Lin Jingyin: The ‘God of Confectionery’ who transformed Japanese culinary culture

Compared to the previous two figures, Lin Jingyin’s name may be less familiar in China, yet he enjoys immense prestige in Japan, where he is revered as “Lord Lin Jingyin.” A seventh-generation descendant of the renowned Song Dynasty recluse poet Lin Bu, Lin Jingyin was born during the turbulent final years of the Yuan Dynasty. In 1350, he arrived in Japan with his friend, the Japanese monk Ryōzan Tokken.

He found that Japanese culinary culture was relatively simple: most snacks were hard, crispy rice-flour crackers. Lin Jingyin discovered that the key reason Japanese people couldn’t produce soft, fluffy flour-based foods was their lack of mastery of flour fermentation.

The culinary revolution

Thus, Lin Jingyin began teaching Chinese fermentation methods. By combining Chinese steamed-bun techniques with local Japanese ingredients, he created the distinctive “Nara Manju” (steamed buns with a sweet filling). This innovation was revolutionary, spreading quickly and becoming an indispensable part of daily life.

Beyond sharing techniques, Lin Jingyin established Japan’s first specialized confectionery shop, “Shioze Sohonke.” This establishment, now over 600 years old and still operating in its 24th generation, has been designated by the Japanese government as an “Important Intangible Cultural Property.”

The status of the wagashi founder

In the history of Japanese culinary culture, Lin Jingyin’s status is irreplaceable. All Japanese confectionery masters regard him as the industry’s founding patriarch, revered as the “God of Sweets” and the “Ancestor of Rice Cakes.” A saying persists in Japan’s confectionery world: “To learn confectionery, first pay homage to Patriarch Lin.” Leading wagashi (traditional Japanese sweets) brands regard him as their spiritual leader, and they often perform annual rituals in which they offer their finest sweets at his memorial.

Reverence transcending borders

These three Chinese figures enshrined in Japanese sacred spaces lived in different eras and contributed to distinct fields. Yet, they share a common thread: each used their talents and goodwill to bring profound, practical blessings to the people of another nation. Xu Fu introduced technology and civilization; Chiang Kai-shek demonstrated tolerance and reconciliation; Lin Jingyin contributed his craftsmanship, enriching Japan’s culinary culture. This history indicates that the reverence of the Japanese people, rooted in genuine gratitude for the tangible improvements to their lives, is a force that can truly transcend national boundaries and past historical grievances.

Translated by Audrey Wang and edited by Helen London

Follow us on X, Facebook, or Pinterest