On May 8, 1958, Mao Zedong addressed senior Communist Party officials at a meeting of the Party’s Eighth National Congress. In the course of his remarks, he compared himself to Qin Shi Huang, the first emperor of China — long condemned in Chinese history for persecuting scholars and ruling through terror. Mao Zedong did not reject the comparison. Instead, he embraced it.

“What does Qin Shi Huang amount to? He only buried 460 scholars alive; we have buried 46,000 scholars alive. We suppressed counter-revolutionaries — didn’t we kill some counter-revolutionary intellectuals? I debated with pro-democracy figures; they accused us of being Qin Shi Huang. I said: ‘You are wrong: We have surpassed Qin Shi Huang a hundredfold.’

“When you berate us for being Qin Shi Huang, for being dictators, we admit it all. It is a pity that you did not say enough, and usually, we have to help you make it more complete.”

Qin Shi Huang unified China in the third century B.C. and is remembered for consolidating power through harsh laws, book burnings, and the execution of dissenting scholars. For centuries, he served as a symbol of absolute tyranny in Chinese political thought. Mao Zedong’s remarks were striking not only for their brutality, but for their candor: He openly acknowledged dictatorship, mass killing, and repression as tools of rule — and spoke of them without remorse.

After the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) established its regime in 1949, Mao Zedong launched a series of political campaigns that mobilized the population through fear, ideology, and violence. These movements left tens of millions dead or persecuted. Yet even at the height of this terror, resistance did not vanish entirely.

Among those who refused to remain silent was a nineteen-year-old university student in Beijing named Wang Rongfen.

A gifted student in a time of upheaval

Wang Rongfen was born in 1947 in Beijing’s Haidian District. From an early age, she stood out academically. She attended Peiyuan Primary School and later gained admission to Beijing No. 101 Middle School, earning top scores in Chinese and mathematics. At 16, she was admitted to Beijing Foreign Studies University, where she began studying German.

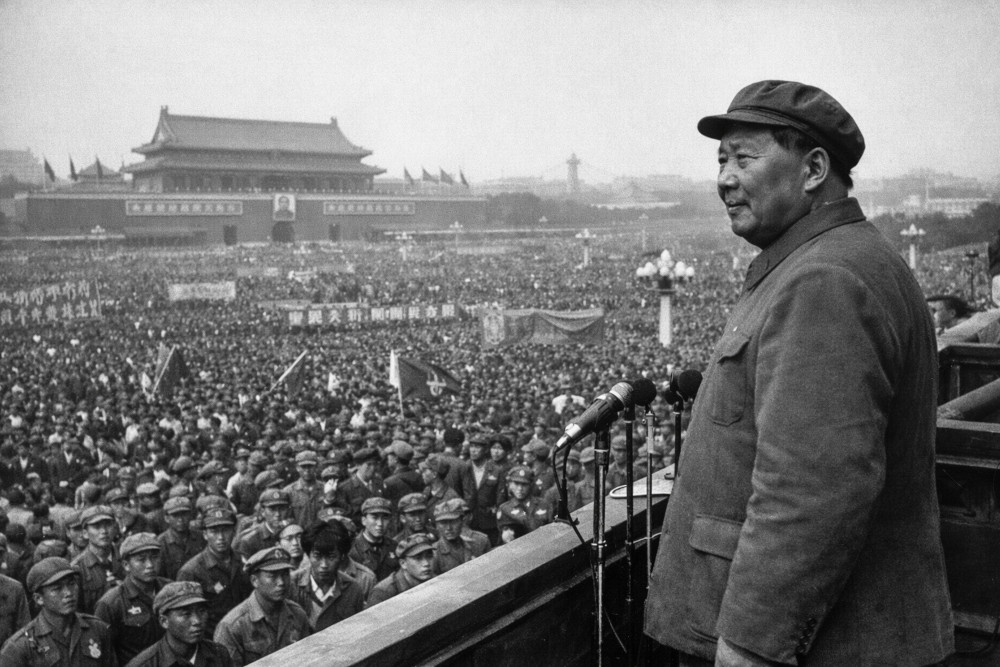

By 1966, Wang was in her fourth year of university and had become a respected student leader. That August, she was selected as a student representative to attend a mass rally in Tiananmen Square, where Mao Zedong appeared before crowds of Red Guards who idolized him with near-religious fervor.

This rally was the first of eight such appearances Mao Zedong would make that year, collectively involving an estimated 12 million Red Guards. In the days that followed, Beijing descended into chaos. Fired by Mao’s words and encouraged by official silence, Red Guard groups poured out of schools and into the streets, launching the campaign to “destroy the Four Olds” — old customs, culture, habits, and ideas. Homes were ransacked, people were beaten and humiliated, and temples and graves were destroyed. The period soon became known as “Red August.”

According to later reports in the Beijing Daily, at least 1,772 people were beaten to death in Beijing between August and September 1966 alone. Among the victims were teachers, school principals, and ordinary citizens.

Witnessing the violence

What Wang Rongfen saw during those weeks left her deeply shaken. The violence was not distant or abstract; it unfolded around her.

Later, in interviews, she recalled streets in turmoil and homes being searched under accusations of espionage and “listening to enemy radio.” She described seeing a pregnant woman paraded through the streets on a truck, her hair forcibly shaved into what was known as a “yin-yang head” — half bald, half long. A heavy placard hung from the woman’s neck, its thin wire cutting into her flesh.

Scenes like this were everywhere. At Wang’s university, located in Beijing’s Weigongcun area, Red Guards desecrated a nearby cemetery. The grave of Qi Baishi, one of China’s most celebrated modern painters, was smashed open. His remains were dragged onto a stage on campus and displayed for public denunciation. Several professors, she later said, took their own lives under the pressure.

One French professor was driven to suicide because his wife was a foreigner. A campus doctor, a graduate of the Whampoa Military Academy, was persecuted because his diploma bore the signature of Chiang Kai-shek, who had once served as the academy’s headmaster.

Wang had studied German and had watched documentaries about the Nazi Holocaust. Comparing those images with what she was witnessing in Beijing, she later said the reality around her felt even more brutal and surreal.

“This country is finished,” she thought. “This world is too dirty to live in.”

A letter that sealed her fate

On September 24, 1966, unable to endure what she was seeing, Wang made a decision that would change her life forever. She wrote a letter addressed directly to Mao Zedong.

In it, she appealed to him not as a distant ruler, but as a Communist Party member and as a leader responsible to the Chinese people. She asked what he thought he was doing, what the chaos unfolding across the country truly meant, and where he was leading China. The Cultural Revolution, she wrote, was not a genuine mass movement, but the result of one man mobilizing the masses through violence.

At the end of the letter, she made a declaration that, under the circumstances, was almost unthinkable: She announced her immediate withdrawal from the Communist Youth League.

That same day, Wang went to a post office near Tiananmen Square, bought stamps from a vending machine, and mailed the letter. She sent copies with identical content to the Communist Party’s Central Committee, her university, and her mother — what she later described as a farewell.

She also carried with her a handwritten German translation of the letter.

Choosing death as a protest

After mailing the letters, Wang walked to a pharmacy on Wangfujing Street and purchased four bottles of dichlorvos, a highly toxic pesticide. She then headed toward the Soviet embassy near Dongzhimen.

At the time, relations between China and the Soviet Union had deteriorated sharply. She hoped that Soviet diplomats would be the first to discover her body — and that news of her death would travel beyond China.

Just short of the embassy, she swallowed all four bottles. She collapsed and lost consciousness.

At 19 years old, in the midst of nationwide hysteria that had swept up even senior Communist officials, Wang Rongfen acted with a clarity rooted in conscience rather than ideology. By writing directly to Mao Zedong and renouncing the Youth League, she knowingly placed herself in mortal danger.

As one observer later put it, her act was like “rushing headlong into a raging fire, fully aware of the destruction that awaited her.”

To be continued.

Translated by Chua BC

Follow us on X, Facebook, or Pinterest