In recent years, sightings of the five-star red flag being flown upside down in China have sparked both ridicule and reflection. The five-star red flag, imposed as the national flag after the CCP’s rise to power in 1949, carries symbolism rooted in communist ideology rather than China’s broader cultural heritage. While officially recognized as the national emblem, it represents not a timeless cultural tradition, but the political dominance of the Chinese Communist Party. Behind its bright colors and patriotic slogans lies a darker story — one that some feng shui masters only discuss in private.

Why Mr. Hu burned the five-star flag

More than a decade ago, my friend Mr. Hu immigrated to the United States. He’s been running a small grocery shop in Chinatown for the past five or six years. His surname is Hu, and his hometown is Jixi in Anhui Province — coincidentally, the ancestral home of former CCP leader Hu Jintao. Because of this, his friends sometimes jokingly call him “Chief Hu,” speculating he might even be a distant relative.

Mr. Hu’s shop faces the main street, and his family lives upstairs, making life and business conveniently connected. Although the U.S. economy has had its ups and downs, his store has remained steady, generating a modest but reliable income.

As China’s National Day approached, Chinatown came alive. The local chamber of commerce raised the five-star red flag on its rooftop, and many shopowners placed the same flag by their doors — meant to display “overseas Chinese loyalty to the motherland.” When I visited Mr. Hu’s shop, I noticed a red flag hanging from a pole in his upstairs window.

“Feeling patriotic, Mr. Hu?” I joked.

Looking slightly embarrassed, he explained: “The chamber of commerce sent it over. They said to hang it up, so I did.”

We chatted briefly, then agreed to meet later for lunch. But when I returned around one o’clock, the flag was gone.

“What happened? Did your patriotic spirit fade that quickly?” I teased.

“You can’t hang it. You can’t even hide it,” he said, lowering his voice. “I burned it.”

A feng shui warning

I was taken aback. Burned it?

He explained that shortly after I left, a customer — who introduced himself as a feng shui master — warned him that the five-star flag was inauspicious and shouldn’t be displayed at the entrance of a home or business. Feng shui practitioners tend to speak with authority, and Mr. Hu took the warning seriously. The man insisted the flag had to be burned in broad daylight with an open flame to dispel the bad energy. So Mr. Hu did just that — in the backyard.

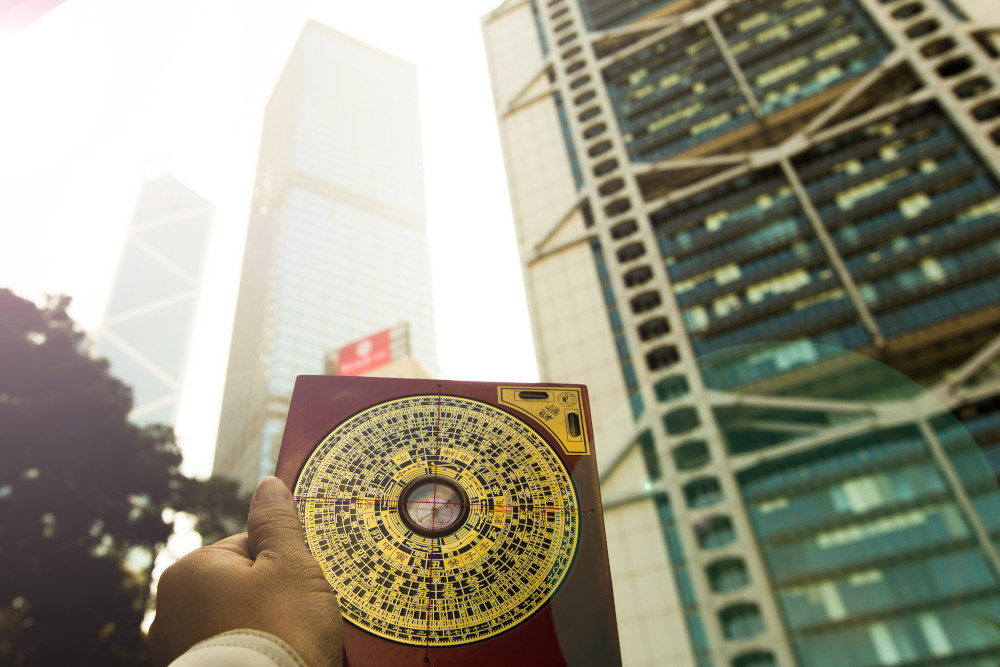

Based on his description, I realized the customer was likely Mr. Ouyang, a well-known feng shui consultant. During the real estate boom a few years ago, he gained popularity for his readings and reportedly helped many clients earn substantial profits. Though I’ve only met him once, I know he’s the son of a high-ranking official and has no ties to anti-CCP groups or dissident movements. I was curious why someone like him would hold such strong views about the flag, so I arranged a meeting under the pretext of seeking feng shui advice.

Interpreting the flag through the I Ching

When we met, I asked him directly: “The five-star red flag is just a national symbol. Why call it unlucky?”

Ouyang replied: “There’s a hexagram in the I Ching called ‘a group of dragons without a leader’ — it’s considered auspicious. Look at the American flag: the stars are equal, the stripes are balanced — no one dominates. But the Chinese flag? One big star leading four small ones — one party above all. That’s a reversed version of the hexagram. It signifies misfortune.”

He continued: “But the problem isn’t just symbolic. Do you know what the color red truly represents? It’s blood. In ancient rituals, flags soaked in blood were used to summon spirits. The red flag creates a field of negative energy — filled with conflict and misfortune. Hanging it over your home invites that energy in. It can affect your family’s wellbeing, your health, your business, your peace of mind.”

I tried to brush it off. “We’ve known since childhood that the red comes from revolutionary martyrs’ blood. It’s symbolic.”

Ouyang nodded: “Yes — and also the blood of those who died in war, in purges, in famine, during the Cultural Revolution. Millions died unjustly under that flag. Their spirits don’t rest. Wherever the red flag is raised, their grievances remain. Bring it into your home, and they follow.”

His words unsettled me. I suddenly remembered the red scarf we were required to wear as schoolchildren — a corner of that same red flag. The thought of it, once proud and bright, now felt cold and suffocating.

Consequences no one sees

I asked Ouyang why he didn’t share this with more people.

“The overseas Chinese community is complicated,” he said. “Many chambers of commerce have ties to the Party. If I say something publicly, I’ll be labeled unpatriotic or subversive — and it’ll ruin my business. So I only say this privately, and only to those who’ll listen — like Mr. Hu.”

Curious about how far he took this belief, I asked: “Would you advise any client to burn the flag?”

“Of course,” he replied. “If I’m being paid to assess feng shui, I have to tell the truth. One client was a leader of a patriotic Chinese association. His home was filled with national flags, but his life was marked by numerous setbacks. After I explained the problem, he quietly removed the flags — and things improved. Last year, during the usual National Day flag-raising, he asked someone else to take his place. The ceremony went fine, but the man who stepped in had a car accident afterward.”

It seemed like a stretch. “Accidents happen all the time,” I said. “It doesn’t necessarily mean there’s a connection.”

Ouyang nodded, but added: “Still, you can check. Look at public records on National Day — there’s always a spike in accidents and incidents around flag-raising sites. It’s a pattern.”

He explained that when the flag is raised, it creates a powerful field — what he called “bloody and aggressive energy mixed with low-spirited vibrations.” Some people are more sensitive and become emotionally or physically affected. It’s not about superstition, he said, but about unseen forces we don’t fully understand.

Feng shui doesn’t care about patriotism

“I can’t see this ‘field’ you talk about,” I said.

“Most people can’t,” Ouyang replied. “But many feel it. As a feng shui consultant, I’ve developed a sensitivity, almost like a sixth sense. For example, the Chinese consulate building flies that flag every day. I won’t go near it. Even driving past, I feel the heaviness. I take another street.”

I asked: “What about people living in China, surrounded by these flags every day?”

“They develop a kind of immunity, like bacteria in the air,” he said. “If you don’t focus on it — don’t stare or think about it — it won’t affect you much. But be careful. That field is attractive. Some people get addicted to the energy. You’ve seen them — rushing to Tiananmen to watch the flag-raising every morning, feeling ‘patriotic.’ But it’s not love of country — it’s spiritual entanglement. Their souls are drawn in.”

Finally, I asked: “Isn’t burning the flag unpatriotic? Shouldn’t we acknowledge that?”

Ouyang’s answer was calm. “Love and hate are subjective. Feng shui isn’t about feelings. It only measures fortune and misfortune — those are objective. I don’t twist bad into good. I tell people what is harmful and what is beneficial. As for patriotism, that’s a political question, and a complicated one in China. Before asking whether you love a country, ask if you love yourself — your family, your children. If so, shouldn’t you create the safest, most harmonious space for them to live in?”

Translated by Eva

Follow us on X, Facebook, or Pinterest