In modern Chinese history, one image is deeply etched in people’s minds: in 1989, on Beijing’s Chang’an Avenue, the lone young man who stood in front of a line of tanks — the “Tank Man.” He had no name, yet he became a symbol of resistance against tyranny and the defense of human dignity. More than 30 years later, in the world of arts and letters, a new “Tank Man” has appeared: internationally renowned Chinese writer Yan Ge-ling.

From literary superstar to ‘being disappeared’

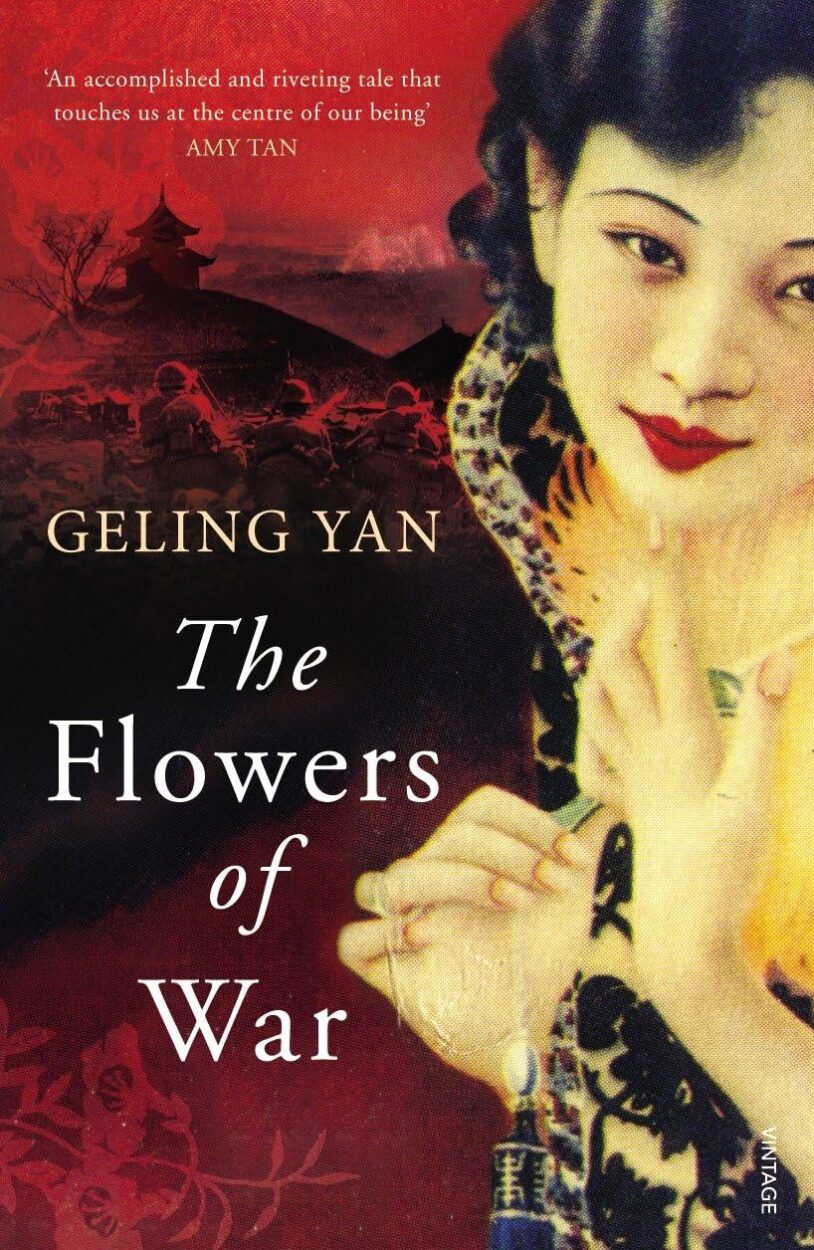

Yan Ge-ling is one of the most popular authors in the Chinese-speaking world. Several of her works — such as The Flowers of War, Fusang, and The Criminal Lu Yanshi — have been adapted into films and won international acclaim. However, in 2020, after publishing an article criticizing the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) for covering up the pandemic, she was instantly blacklisted by Beijing. Once a “guest of honor,” she became an “outcast” overnight. Her novels were forcibly removed from publishers’ shelves, film adaptation rights were stripped away, and even her name was erased. Under the CCP’s censorship system, Yan Ge-ling became an “unmentionable.” Yet she refused to remain silent.

The ‘One Second’ incident: A battle over literary credit

In 2021, director Zhang Yimou’s film One Second was released overseas. The film was widely recognized as being adapted from Yan Ge-ling’s novel, but under CCP pressure, her name was deleted. The right to be credited — the most basic right of an author — was replaced by “censorship.”

Faced with this blatant abuse of power, Yan and her husband, Lawrence Walker, did not back down. They staged a protest outside a Berlin cinema and hired lawyers to launch legal action in Germany, France, and the United States. They spoke out publicly, writing to major distributors demanding that posters and trailers carry the line “Adapted from the work of Yan Ge-ling.”

The campaign consumed vast amounts of money and energy. Most of the film industry chose silence; only a few cinemas complied. One producer even threatened her: “If you keep this up, we’ll report you to the China Film Bureau.” Such threats were essentially an extension of state violence. Walker said the situation reminded him of the Tank Man: one person standing against an entire system. Yan Ge-ling had become the Tank Man of the literary world.

Publishing freedom: From being banned to self-reliance

After being banned by Chinese publishers, Yan and Walker took another path: They founded their own publishing house. Her new work, Mirati, was distributed via Amazon, truly breaking through the CCP’s publishing censorship. This was not only Yan’s personal breakthrough, but also opened a path for other silenced authors. Walker revealed that other blacklisted writers have already submitted their works to their press, hoping to “regain freedom.” Behind the CCP’s iron curtain, words are often burned and thoughts erased. But Yan has shown through her actions that as long as one dares to break through, there is a way to find freedom in the world.

The CCP’s fear and the courage of individuals

What the CCP fears most has never been weapons, but ideas. Because once ideas escape censorship, they can ignite the awakening of more people. Yan chose to stand up not only for herself, but also for the dignity of literature, for intellectual property, and above all, for truth and freedom.

Her struggle exposes a brutal reality: in mainland China, law has become a tool of the regime, and literature and art have been reduced to political appendages. Only by going beyond national borders can one rely on genuine legal systems to defend one’s rights.

The ‘Tank Man’ of the arts

Some might ask: Is such resistance worth it? Walker’s answer is — “You can’t do anything, or you’ll just sit there and be bullied.” Yan’s image is like that of Tank Man decades ago: she knows she is facing a giant machine, yet she still chooses not to step aside. This is a form of moral courage, a writer’s responsibility.

In today’s China, censorship is tightening, and the space for freedom is shrinking rapidly. But precisely because of this, every person who dares to stand up becomes all the more precious. Yan’s story tells us: even literature can become a weapon against tyranny; even writers can become the Tank Man of their time.

Zhang Yimou: Which road did he choose?

Yan Ge-ling’s novel The Criminal Lu Yanshi depicts an intellectual turned “prisoner” by politics, his fate crushed by the times. Zhang Yimou, once a rebellious filmmaker, directed early works such as Red Sorghum, To Live, and Not One Less, which revealed profound insights into humanity, suffering, and history. But since the 2000s, he has increasingly chosen the path of “political correctness,” becoming a court artist of the system.

If we ask “Which road to choose?” the contrast is clear:

- Yan Ge-ling chose the road of “no compromise.” She knew that publicly criticizing the CCP would inevitably mean being banned, yet she persisted in speaking the truth and built her own publishing channels overseas. She became the “Tank Man of the literary world,” standing alone against an entire system.

- Zhang Yimou chose the road of “compromise.” He accepted cuts, deletions, and name removals under CCP censorship, even adding “false happy endings” just to pass review. He shifted from being an artist to a cultural symbol serving power. Although he is still enjoying fame and resources, the soul of his works has gradually faded.

Thus, the contrast between Yan Ge-ling and Zhang Yimou represents a fundamental crossroads for Chinese intellectuals and artists: to be like Lu Yanshi in The Criminal Lu Yanshi, suffering but holding to conscience, or to become the “artist the system needs,” trading integrity for survival and glory. Zhang Yimou: Which road did he choose? This is not only a question for Zhang Yimou, but a question for all of China’s artists and cultural workers.

Follow us on X, Facebook, or Pinterest