Do you believe in divination, that destiny can be foretold — and even rewritten? Amid the turbulent years of the Republic of China, an extraordinary figure emerged. He held no title, commanded no armies, and yet his words could sway the decisions of generals, tycoons, and gang leaders.

Chiang Kai-shek once sought his counsel. The underworld kingpin Du Yuesheng treated him with deference. With a gaze that seemed to pierce the soul, he could read the rise and fall of fortune — and warn of calamities yet unseen. His name was Yuan Shushan — the man hailed as the Republic’s Number-One Diviner.

The making of a master diviner

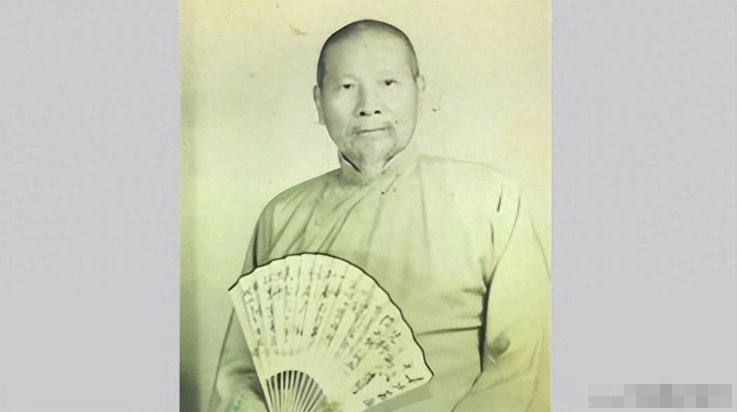

Born in 1881, the seventh year of the Guangxu Emperor’s reign, Yuan Shushan came from Zhenjiang, a city where the Yangtze meets the Grand Canal. His family’s heritage was steeped in both healing and prophecy. His father, Yuan Kaichang, was a respected physician and a skilled diviner. From childhood, Yuan absorbed the arts of diagnosis and fate-reading, developing a fascination with both medicine and numerology.

As a young man, he studied at Peking University and later in Japan, returning to China with a rare blend of traditional Chinese learning and modern Western ideas. Though he could easily have pursued an official career, the lure of public office never stirred him. Instead, he returned home to continue his family’s dual traditions.

Initially, medicine was his primary calling, with divination serving as a quiet sideline. Yet during consultations, he would sometimes perceive other troubles beyond the illness at hand. He might tell a patient, “Your ailment will be cured with this prescription, but I see redness in your left eye and a bluish hue in your right — beware of a blood-related mishap within the month.” Or if someone lamented a lost heirloom while receiving treatment, he might advise: “Look to the southwest corner of your house, near water.” Such readings, uncannily accurate, began to spread his name far beyond his hometown.

As word of his skills spread, patients came less for remedies and more for revelations. Over time, the trickle of divination seekers grew until they outnumbered the sick; medicine became a sideline, and prophecy became the actual work. Yuan shuttered his medical practice and transformed Runde Tang — the “Hall of Benevolence and Virtue” his family had long used as their clinic — into a fortune-telling hall. Within a few short years, he had risen to the top tier of prognostic masters in Zhenjiang, and his reputation echoed across the Jiangsu and Zhejiang provinces.

A book that saved traditional medicine

In the early Republic, China teetered on the edge of sweeping change. After a series of humiliating defeats at the hands of foreign powers, some Western-educated officials and intellectuals insisted the nation must abandon its “backward” traditions and fully embrace Western ways. Practices like traditional Chinese medicine — and even fate-reading — were denounced as unscientific and targeted for suppression.

The backlash was immediate. Practitioners and ordinary people alike bristled at the thought: Could thousands of years of accumulated wisdom be discarded overnight? The legendary physicians Bian Que, Hua Tuo, Sun Simiao, and Li Shizhen had left behind a vast record of cures and methods — were these to be dismissed as mere superstition?

Yuan Shushan, raised in a household where medicine and divination stood side by side, refused to stand idle. He compiled and published The Exploration of Chinese and Western Physiognomy (Zhongxi Xiangren Tanyuan), blending Chinese face-reading and physiognomy with contemporary Western theories. His aim was clear: to show that these ancient arts possessed their own internal logic and rational foundation — and were not to be erased in the rush to modernize.

Tan Yankai — then Premier of the Executive Yuan and a conservative scholar-statesman steeped in the classics — read Yuan’s book and was deeply impressed. A tolerant patron of traditional culture, Tan recognized the shared roots of medicine and divination, and he publicly opposed efforts to abolish them. His endorsement brought Yuan both prestige and protection, lending legitimacy to the arts under threat.

Yet the battle was far from one-sided. Among the most vocal opponents of traditional Chinese medicine was Wang Jingwei, a powerful political figure who openly called for its ban. Fate, however, had other plans. When Wang’s own mother-in-law was stricken with severe dysentery and Western doctors failed to help, the renowned physician Shi Jinmo was summoned. After taking her pulse and prescribing a 10-day regimen, Shi calmly predicted a full recovery within that time — and his words proved true.

Shi refused lavish rewards, instead urging Wang to reconsider his stance. Shaken by the experience, Wang softened his opposition. Thus, Yuan’s scholarship and Shi’s clinical triumph together helped shield Chinese medicine and its allied traditions from eradication. Truly, Heaven’s arrangements can be wondrous.

The master’s sight: Famous predictions

Yuan’s fame grew on the strength of predictions that were neither vague nor conveniently forgotten — but specific, dramatic, and borne out by events that followed.

One of the earliest to test him was a powerful warlord of the Zhili faction, a man already familiar with the study of fate. Impressed by Yuan’s reading, he offered him a position, which Yuan declined. The divination came with two warnings: grave misfortune in his early fifties, and a blood-related danger at sixty. Both struck true. The warlord lost power at 51, and years later died from an infected wound after biting into a mutton dumpling bone — a death some whispered was no accident.

His reputation among the military elite brought other figures to his door. General He Yingqin sought a reading and, deeply impressed, introduced Yuan to Chiang Kai-shek. Chiang, already a believer in numerology, admired Yuan’s dignified, forthright manner. Soon, statesmen, wealthy merchants, and cultural luminaries were seeking him out.

Among them was Miao Bin, an influential legislator and former high official. Yuan foresaw a prosperous future, but added a puzzling warning: “Wu will harm you.” The words seemed meaningless at the time. Years later, during the war, Miao sided with Wang Jingwei’s puppet regime. After Japan’s surrender, facing trial for treason, he sought help from his old associate Wu Zhihui. Wu’s impassioned plea for clemency instead stirred Chiang Kai-shek’s suspicion, prompting him to order Miao’s execution without retrial. Miao became the first collaborator executed after the war — a chilling fulfillment of Yuan’s phrase.

As wartime turmoil engulfed China, Yuan moved to Shanghai, where his fame spread nationwide. In 1938, after the fall of Nanjing, a group of officers fled to the city. Among them was Guo Qi, a skeptic of fortune-telling who accompanied others out of courtesy. Yet when Yuan studied his face and palms, he issued a startling prediction: Guo would rise to become a major general and corps commander near age forty, would face disaster fighting in the desert, yet somehow survive, and afterward enjoy steady good fortune.

History confirmed every detail. Guo attained command at 40, suffered a catastrophic desert defeat in which his troops perished and he nearly died of thirst, was rescued by enemies, and eventually repatriated. After the war, he resettled in Taiwan and lived the stable life Yuan had foretold. In his memoir, A Record of Blood and Tears in the Fall of the Capital, Guo chronicled both the horrors of Nanjing and Yuan Shushan’s remarkable divination skills.

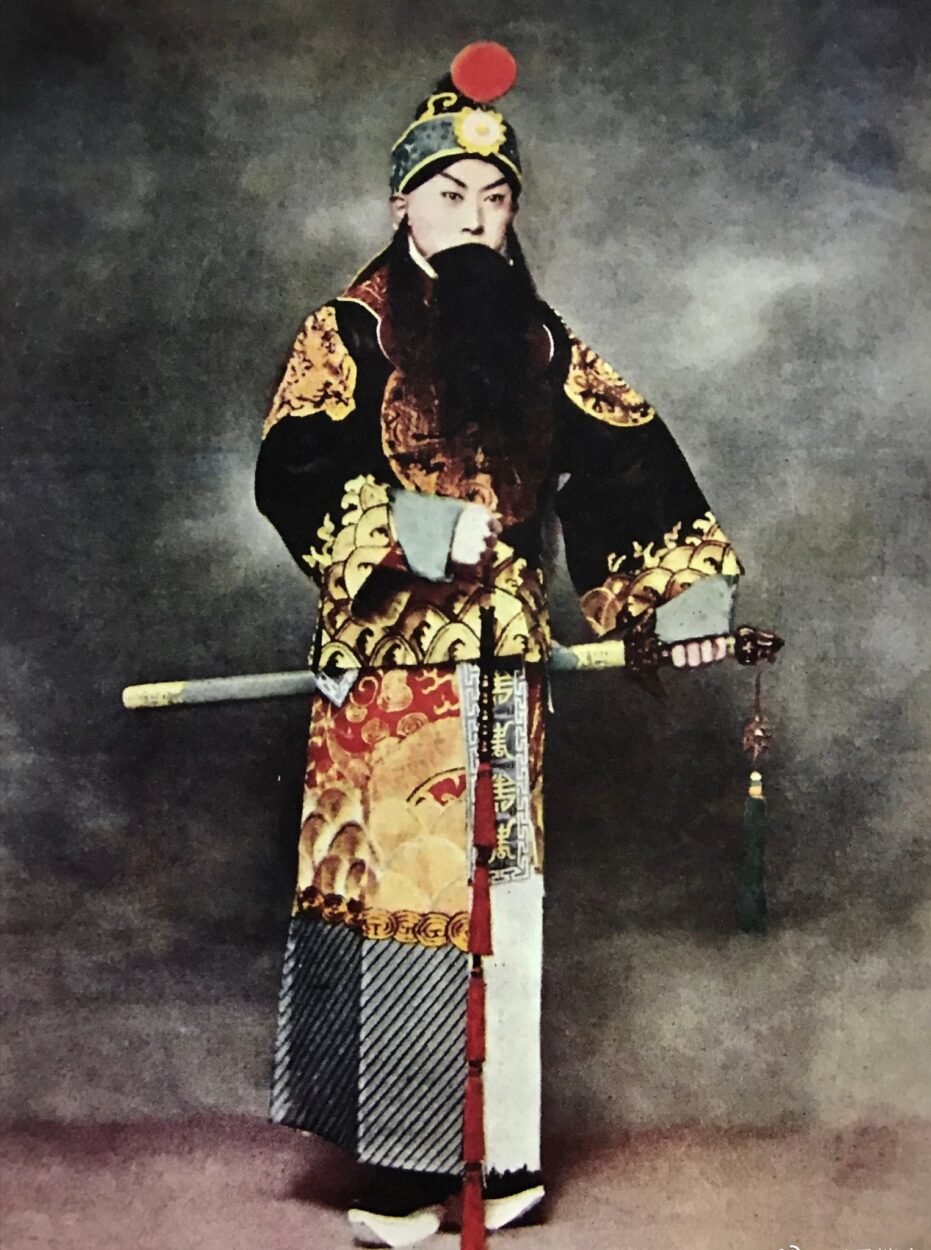

Yuan’s foresight extended beyond military leaders. Ma Lianliang, one of the three great Peking-opera masters, visited him. After enduring much hardship in Hong Kong following the war, Ma returned to mainland China in 1951. Before leaving, he visited Yuan, who told him he had “fifteen years of good fortune.” True to Yuan’s words, Ma’s life during this period, though marked by political upheavals, included successful performances, recognition of his artistry, and periods of relative stability. Remarkably, he died suddenly in December 1966, exactly 15 years after leaving Hong Kong. People took Yuan’s forecast as yet another confirmation that he could perceive the overall arc of a life.

When divination misses: The case of Du Yuesheng

As is bound to happen in the human world, even the greatest diviners are not infallible.

During his years in Shanghai, Yuan’s growing fame sometimes made him a target for extortion. Gangsters occasionally threatened him, but Huang Jinrong, the city’s notorious tycoon, visited Yuan with great respect and discreetly signaled his men to leave the diviner unharmed. Through this connection, Huang’s successor, Du Yuesheng, became acquainted with Yuan and eventually befriended him.

In 1949, as Du’s health declined while he was in exile in Hong Kong, he asked Yuan how long he would live. Yuan confidently predicted he had at least 10 more years, potentially reaching 73. Yet Du, seeking additional assurance, secretly consulted a Taiwanese diviner known as the “June-Rest Master,” who warned that he would not survive past 64 and specifically flagged 1951 as a dangerous year.

On August 16, 1951, Du died at the age of 63. Yuan’s forecast had overshot reality by roughly a decade. The episode became a rare reminder that, even for a master like Yuan, divination could not account for every twist of fate — and that forces beyond prediction ultimately shape human lives.

Can fate be altered?

The 10-year discrepancy in Du Yuesheng’s case has three commonly suggested interpretations:

- Self-fulfilling surrender: According to Du’s son, after hearing the grim prediction, Du’s spirit may have collapsed. He became bedridden and weakened, possibly losing the will to live — a factor that might have shortened his life.

- A compassionate comfort: Yuan once explained: “There are three types of people who come for an astrologer’s advice: those facing great mental or emotional challenges; those obsessed with fame and fortune; and those who are desperate. Facial observation is critical in giving proper advice.” It is possible Yuan knew the true prognosis, but offered Du hope in his final years — a “kind lie” intended to spare him a fearful death.

- Fate is dynamic: Yuan consistently taught that destiny is influenced by the heart’s intentions and karma. Predictions are not absolute; lives can change depending on choices, actions, and inner resolve.

Each interpretation reflects the subtlety of Yuan’s art — that while he could perceive the arc of a life, the future was never entirely fixed.

Yuan Shushan on fate: A measured philosophy

In 1947, Yuan wrote about fate in a Shanghai paper, and his reflections remain striking in their clarity and depth: “Ming” (命) refers to a person’s innate life pattern; “yun” (運) refers to the phases and events one encounters. The calculations of fate are based on the Five Elements and the Four Pillars. When large cycles (大運) arrive, yin-yang energies shift; when annual cycles (流年) come, heavenly stems and earthly branches change. In other words, major cycles are like the roads you travel; annual cycles are like the people you meet along the way. They interact dialectically and must be read with nuance.”

Some parts of destiny are knowable and calculable through the reasoning of yin-yang and the Five Elements; others are influenced by karma and moral cause-and-effect, which are not so predictable. Seeking divination is not a matter of idle curiosity, but a tool to help people avoid misfortune and embrace blessings, which explains the enduring popularity of numerology.

Yuan emphasized that external measures, such as feng shui, talismans, or name changes, cannot overcome the human heart or karmic consequences. The real foundation lies in the inner strength developed through moral cultivation and upright character. Rearranging tombs or changing names will not save a person with a corrupt mind; a kind and upright person will naturally enjoy favorable conditions. As the saying goes: “Blessed people inhabit blessed places, and blessed places host blessed people.”

Yuan held that the I Ching (Book of Changes) was the supreme guide to virtuous living. Those who deeply grasped its lessons would not need to rely on auxiliary aids such as feng shui, talismans, or name changes to improve their fate. A clear mind and a sincere heart devoted to goodness would naturally be blessed and protected by the divine. In other words, those who truly understood the I Ching would not require divination.

In his later years, Yuan urged his successors to focus on teaching the moral lessons of the I Ching, rather than becoming preoccupied with sorcery, fortune-telling techniques, or other superficial arts.

The end of an era: His son’s path

In his later years, Yuan Shushan reflected on the life he had led as a master diviner. He understood that divination was a profound art, carrying a heavy responsibility and knowledge that should not be taken lightly. Navigating the influence, expectations, and consequences that such insight brought was never easy.

Yuan may also have foreseen the course of the modern world. Having already faced skepticism and pushback against traditional practices for years, perhaps he saw that mankind, in its rapid modernization, might mishandle or misunderstand the knowledge and responsibility of divination. Medicine, by contrast, offered a tangible, practical path, better suited to the world humanity was moving toward.

When his son, Yuan Furu, expressed a desire to learn divination, Yuan gently refused. He instructed that the divination tools be destroyed after his death, and that his son should devote himself to medicine. It was not a rejection of divination, nor a doubt in his son’s ability, but a careful choice to preserve the integrity of the art and safeguard its secrets.

Yuan Furu honored his father’s wishes. He destroyed the divination tools, moved to Japan to study medicine, and later became a distinguished physician. In this act, the era of Yuan Shushan as a master diviner quietly ended. Yet his wisdom, foresight, and moral insight endure — not in instruments or forecasts, but in the lives he touched and the example he left behind.

Closing thoughts

Yuan Shushan’s life stood at the crossroads of tradition and modernity — a man of books and clinics, of prognostication and humane care. He believed that destiny could be read, yet he insisted that character and karma ultimately shape its course. His message was quiet but firm: Tools and techniques may guide us, but it is the moral strength of the heart that determines one’s path and ultimately moves the world.

Translated by Katy Liu and edited by Tatiana Denning

Follow us on X, Facebook, or Pinterest